Visiting My Mother’s Wars

My father has taken to dosing my mother with melatonin at night.

Or she would rise at 3 to watch TV and later, after dinner, not know him.

My mother stands pointing at all the flowers gone to the deer;

look at that, they took everything, all of it, even that,

she pokes one final time at a bed of moss roses.

She calls me to the vegetable garden, protected by chicken wire

and points look at that, nothing is growing this year,

it’s awful then tears out the cucumber.

Later, hands on hips, where’s your father? “In the garage,” I say

and her eyes narrow, and suspicious, she calls upstairs,

Bob?! You up there? Bob? He’s always disappearing.

She sits in front of a stack of books, Ugh, there are no good

books anymore. I don’t like any of these, none of them,

even the authors I used to love. What’s for dinner? Soup?

What’s for dinner? I look up from my book, “I think Dad is grilling.”

He thinks he’s boss now. She sits on the couch, arms folded,

What’s for dinner? I can defrost Minestrone.

When she’s not looking, I replant the cucumbers and point,

“Look at how good they are doing, it’s only June.”

My father secretly checks and double checks the stove.

After I’m gone, my mother tells my father that her ex-husband loved cars

and his garage was filled with them. He takes her hand,

says, “That’s me. I’m the only one.”

by E.A. Wilberton

from Rattle #75, Spring 2022

While it is fashionable for some female academics, journalists and social commentators to declare the

While it is fashionable for some female academics, journalists and social commentators to declare the  When the

When the This paper links two things that are often dealt with separately when discussing what we mean by the word “just” in the notion of a “just transition”. On the one hand, activists and reformers – especially those promoting the United States (US) version of the Green New Deal (GND) – see this as an opportunity to empower marginalised populations and redistribute wealth-generating assets using the state in the form of green industrial policy. On the other hand lies private finance, especially in the form of asset managers, who own huge swathes of global companies. Their investment decisions are critical to the transition, but they have no intention of allowing such a redistribution of assets and power. Indeed, they see the function of the state as using its balance sheet to insure private investors against losses. We use these competing notions of “just” as a way to discuss how we can have a transition that leverages the investments of the private sector without once again simply giving capital everything it wants at the expense of everyone else.

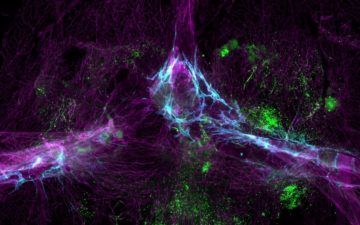

This paper links two things that are often dealt with separately when discussing what we mean by the word “just” in the notion of a “just transition”. On the one hand, activists and reformers – especially those promoting the United States (US) version of the Green New Deal (GND) – see this as an opportunity to empower marginalised populations and redistribute wealth-generating assets using the state in the form of green industrial policy. On the other hand lies private finance, especially in the form of asset managers, who own huge swathes of global companies. Their investment decisions are critical to the transition, but they have no intention of allowing such a redistribution of assets and power. Indeed, they see the function of the state as using its balance sheet to insure private investors against losses. We use these competing notions of “just” as a way to discuss how we can have a transition that leverages the investments of the private sector without once again simply giving capital everything it wants at the expense of everyone else. The brain is the body’s sovereign, and receives protection in keeping with its high status. Its cells are long-lived and shelter inside a fearsome fortification called the blood–brain barrier. For a long time, scientists thought that the brain was completely cut off from the chaos of the rest of the body — especially its eager defence system, a mass of immune cells that battle infections and whose actions could threaten a ruler caught in the crossfire. In the past decade, however, scientists have discovered that the job of protecting the brain isn’t as straightforward as they thought. They’ve learnt that its fortifications have gateways and gaps, and that its borders are bustling with active immune cells.

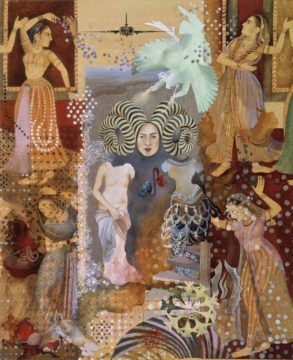

The brain is the body’s sovereign, and receives protection in keeping with its high status. Its cells are long-lived and shelter inside a fearsome fortification called the blood–brain barrier. For a long time, scientists thought that the brain was completely cut off from the chaos of the rest of the body — especially its eager defence system, a mass of immune cells that battle infections and whose actions could threaten a ruler caught in the crossfire. In the past decade, however, scientists have discovered that the job of protecting the brain isn’t as straightforward as they thought. They’ve learnt that its fortifications have gateways and gaps, and that its borders are bustling with active immune cells. In 2019, two Persian paintings sold in a private-auction house, in London, for roughly eight hundred thousand pounds each. The paintings were illuminated manuscripts, or “miniature” paintings, and they belonged to the same book: a fifteenth-century edition of the Nahj al-Faradis, which narrates Muhammad’s journey through the layers of heaven and hell. The original book, once an artistic masterpiece, had been ripped apart, reduced to sixty lavish images. Bound, the manuscript was likely worth a few million pounds; dismembered, its contents have sold for more than fifty million.

In 2019, two Persian paintings sold in a private-auction house, in London, for roughly eight hundred thousand pounds each. The paintings were illuminated manuscripts, or “miniature” paintings, and they belonged to the same book: a fifteenth-century edition of the Nahj al-Faradis, which narrates Muhammad’s journey through the layers of heaven and hell. The original book, once an artistic masterpiece, had been ripped apart, reduced to sixty lavish images. Bound, the manuscript was likely worth a few million pounds; dismembered, its contents have sold for more than fifty million. “I’m stricken by the ricochet wonder of it all,” poet Diane Ackerman wrote in her sublime

“I’m stricken by the ricochet wonder of it all,” poet Diane Ackerman wrote in her sublime  What I take from this is not so much that Power is a radical but rather that he believes style is not a substitute for ideas, nor should it be used as an evasive measure to obscure areas of darkness or deployed as a bully in debate. His own clear prose works hard at allowing him to do some expansive thinking in what is still a concise amount of space. In the longer essays various big ideas (example: the Apocalypse) are explored in some depth with a lot of ground crisply covered in relatively few pages.

What I take from this is not so much that Power is a radical but rather that he believes style is not a substitute for ideas, nor should it be used as an evasive measure to obscure areas of darkness or deployed as a bully in debate. His own clear prose works hard at allowing him to do some expansive thinking in what is still a concise amount of space. In the longer essays various big ideas (example: the Apocalypse) are explored in some depth with a lot of ground crisply covered in relatively few pages. We have probably all seen images from Goya’s so-called Black Paintings whether we realize it or not. The image known as Saturn Devouring His Son (Goya did not title these works, the titles came from later art historians) is especially ubiquitous. The painting depicts the ancient Greek and Roman mythological story in which Saturn (Kronos in the Greek) eats his own children. You’ll remember that there was a prophecy. One of the children of Saturn would overthrow him. Saturn’s solution to this problem was to eat all the children. This worked for a time, until, inevitably, it did not. But that is another story.

We have probably all seen images from Goya’s so-called Black Paintings whether we realize it or not. The image known as Saturn Devouring His Son (Goya did not title these works, the titles came from later art historians) is especially ubiquitous. The painting depicts the ancient Greek and Roman mythological story in which Saturn (Kronos in the Greek) eats his own children. You’ll remember that there was a prophecy. One of the children of Saturn would overthrow him. Saturn’s solution to this problem was to eat all the children. This worked for a time, until, inevitably, it did not. But that is another story. Imagine you heard a scientist saying the following:

Imagine you heard a scientist saying the following: On or around 1939 debates about international political economy changed. Over the course of the Cold War, economic nationalism—the attempt to use the state to advance a country’s economic interests—was crowded out of official discourse by two competing universalisms, communism on one side and liberalism on the other. Over the last few decades, however, this opposition has been scrambled. First Marxist universalism failed; the Sino-Soviet split fractured the communist project before the USSR collapsed altogether. Then, after a brief period in the sun on the international stage, liberal universalism too began to falter in a declining arc from Iraq and the Global Financial Crisis to Donald Trump’s victory on an “America First” platform.

On or around 1939 debates about international political economy changed. Over the course of the Cold War, economic nationalism—the attempt to use the state to advance a country’s economic interests—was crowded out of official discourse by two competing universalisms, communism on one side and liberalism on the other. Over the last few decades, however, this opposition has been scrambled. First Marxist universalism failed; the Sino-Soviet split fractured the communist project before the USSR collapsed altogether. Then, after a brief period in the sun on the international stage, liberal universalism too began to falter in a declining arc from Iraq and the Global Financial Crisis to Donald Trump’s victory on an “America First” platform. For more than a half-century, America has been a world leader in space, from the space race of the 1960s to the shuttle to numerous deep space probes. But this leadership has often been reluctant — and in tension with a public that has been at best ambivalent and at worst outright opposed to endeavors to explore the universe. Many Americans have little interest in space and would prefer to spend money

For more than a half-century, America has been a world leader in space, from the space race of the 1960s to the shuttle to numerous deep space probes. But this leadership has often been reluctant — and in tension with a public that has been at best ambivalent and at worst outright opposed to endeavors to explore the universe. Many Americans have little interest in space and would prefer to spend money  On a rainy afternoon in mid-April, the singer and songwriter Angel Olsen steered a Subaru through Asheville, North Carolina, while a cardboard box of VHS tapes clattered in the back seat. Olsen, who is thirty-five, had recently excavated them from her childhood home, in St. Louis. Some promised footage of significant events—“Angel’s Graduation,” “Angel’s First Day of Preschool”—and others were labelled “the pokemon” and “world premiere dark horizon.” After pulling up at a video-restoration shop, Olsen did some hasty sorting in the parking lot, trying to decide which tapes were worth dusting off with a tissue and which ones she could toss. Olsen, who was adopted when she was three years old, has spent much of the past two years figuring out what to hold on to and what to surrender. In 2021, her adoptive mother and father died two months apart (her mother, from heart failure, at age seventy-eight; her father, in his sleep, at eighty-nine), shortly after she realized and told them she was gay. Ever since, Olsen has been sifting through the material and psychological aftermath.

On a rainy afternoon in mid-April, the singer and songwriter Angel Olsen steered a Subaru through Asheville, North Carolina, while a cardboard box of VHS tapes clattered in the back seat. Olsen, who is thirty-five, had recently excavated them from her childhood home, in St. Louis. Some promised footage of significant events—“Angel’s Graduation,” “Angel’s First Day of Preschool”—and others were labelled “the pokemon” and “world premiere dark horizon.” After pulling up at a video-restoration shop, Olsen did some hasty sorting in the parking lot, trying to decide which tapes were worth dusting off with a tissue and which ones she could toss. Olsen, who was adopted when she was three years old, has spent much of the past two years figuring out what to hold on to and what to surrender. In 2021, her adoptive mother and father died two months apart (her mother, from heart failure, at age seventy-eight; her father, in his sleep, at eighty-nine), shortly after she realized and told them she was gay. Ever since, Olsen has been sifting through the material and psychological aftermath. RICHARD WILLIAMS DEMANDS GLORY. The pursuit of glory is revised madness, the ambition of addicts, to get so high they collapse, and are forced to repeat the ascent as if for the first time. It’s preemptive repentance disguised as innocent yearning to win. You have to need vindication to need victory so desperately. Richard Williams is looking for redemption. In a scene from a 1990s video of Richard, father of tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams, we see him genuflecting on a tennis court in Compton, California, in front of a shopping cart full of tennis balls—the ground swells with them. He’s gathering the splayed balls and placing them into red plastic milk crates with the reverence of a praise dancer. What altar is this? A shrine of crumbling adobe, chalk, felt, and plastic. What utter fixation on the unglamorous, what risk of a dedication with no yield? What we know now turns the pathos in Richard’s gesture here into dramatic irony. The menial duties of this father intent on training his daughters to be the best athletes in the world will be redeemed. He will not kneel and scour the ground for these fuzzy green chess pieces in vain.

RICHARD WILLIAMS DEMANDS GLORY. The pursuit of glory is revised madness, the ambition of addicts, to get so high they collapse, and are forced to repeat the ascent as if for the first time. It’s preemptive repentance disguised as innocent yearning to win. You have to need vindication to need victory so desperately. Richard Williams is looking for redemption. In a scene from a 1990s video of Richard, father of tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams, we see him genuflecting on a tennis court in Compton, California, in front of a shopping cart full of tennis balls—the ground swells with them. He’s gathering the splayed balls and placing them into red plastic milk crates with the reverence of a praise dancer. What altar is this? A shrine of crumbling adobe, chalk, felt, and plastic. What utter fixation on the unglamorous, what risk of a dedication with no yield? What we know now turns the pathos in Richard’s gesture here into dramatic irony. The menial duties of this father intent on training his daughters to be the best athletes in the world will be redeemed. He will not kneel and scour the ground for these fuzzy green chess pieces in vain.