Daniel Oberhaus in Harvard Magazine:

FOR THE PAST DECADE, China has led the world in advanced-facial recognition systems. Chinese companies dominate the rankings of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Face Recognition Vendor Test, considered the accepted standard for judging the accuracy of these systems, and Chinese research papers on the subject are cited almost twice as often as American ones. Many experts recognize the importance of facial-recognition and other artificial-intelligence applications for promoting future economic growth through productivity gains, which makes understanding how China came to dominate this field a competitive concern. And after years of research, Harvard assistant professor of economics David Yang believes he’s discovered an explanation for the Chinese companies’ advantage.

FOR THE PAST DECADE, China has led the world in advanced-facial recognition systems. Chinese companies dominate the rankings of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Face Recognition Vendor Test, considered the accepted standard for judging the accuracy of these systems, and Chinese research papers on the subject are cited almost twice as often as American ones. Many experts recognize the importance of facial-recognition and other artificial-intelligence applications for promoting future economic growth through productivity gains, which makes understanding how China came to dominate this field a competitive concern. And after years of research, Harvard assistant professor of economics David Yang believes he’s discovered an explanation for the Chinese companies’ advantage.

In a recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, Yang and his colleagues found that authoritarian states like China may have an inherent and decisive advantage over liberal democracies in facial-recognition innovation. Their secret? The flow of massive amounts of surveillance data to private AI companies that develop facial-recognition software for local police departments.

More here.

Jokes, sarcasm and humor require understanding the subtleties of language and human behavior. When a comedian says something sarcastic or controversial, usually the audience can discern the tone and know it’s more of an exaggeration, something that’s learned from years of human interaction.

Jokes, sarcasm and humor require understanding the subtleties of language and human behavior. When a comedian says something sarcastic or controversial, usually the audience can discern the tone and know it’s more of an exaggeration, something that’s learned from years of human interaction. In all of physical law, there’s arguably no principle more sacrosanct than the second law of thermodynamics — the notion that entropy, a measure of disorder, will always stay the same or increase. “If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell’s equations — then so much the worse for Maxwell’s equations,” wrote the British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington in his 1928 book The Nature of the Physical World. “If it is found to be contradicted by observation — well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.” No violation of this law has ever been observed, nor is any expected.

In all of physical law, there’s arguably no principle more sacrosanct than the second law of thermodynamics — the notion that entropy, a measure of disorder, will always stay the same or increase. “If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell’s equations — then so much the worse for Maxwell’s equations,” wrote the British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington in his 1928 book The Nature of the Physical World. “If it is found to be contradicted by observation — well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.” No violation of this law has ever been observed, nor is any expected. Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant and the

Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant and the  THE CARTHAGINIANS WERE

THE CARTHAGINIANS WERE On 4 March, Christopher Jackson tweeted that he was leaving the University of Manchester, UK, to work at Jacobs, a scientific-consulting firm with headquarters in Dallas, Texas. Jackson, a prominent geoscientist, is part of a growing wave of researchers using the #leavingacademia hashtag when announcing their resignations from higher education. Like many, his discontent festered in part owing to increasing teaching demands and pressure to win grants amid lip-service-level support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On 4 March, Christopher Jackson tweeted that he was leaving the University of Manchester, UK, to work at Jacobs, a scientific-consulting firm with headquarters in Dallas, Texas. Jackson, a prominent geoscientist, is part of a growing wave of researchers using the #leavingacademia hashtag when announcing their resignations from higher education. Like many, his discontent festered in part owing to increasing teaching demands and pressure to win grants amid lip-service-level support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Doocot or dookit is the Scottish term for a dovecote or columbarium; a structure built to nest and breed domesticated pigeons. Some doo men keep their champion pigeons in doocots cut into attic spaces or adapted garden sheds, but on the schemes I lived on, we had neither attics nor gardens, and so the men who wanted to keep pigeons built their lofts out on any piece of unclaimed ground. Aesthetically they have little in common with the traditional stone dovecotes you might find on the grounds of a manor house. The doocots I remember were monolithic towers, twenty feet tall, and they were built from salvaged materials: old Formica tabletops, screwed to corrugated iron and offcuts of MDF. It gave most doocots a rickety charm, which the men tried to disguise by painting the whole thing a uniform colour.

Doocot or dookit is the Scottish term for a dovecote or columbarium; a structure built to nest and breed domesticated pigeons. Some doo men keep their champion pigeons in doocots cut into attic spaces or adapted garden sheds, but on the schemes I lived on, we had neither attics nor gardens, and so the men who wanted to keep pigeons built their lofts out on any piece of unclaimed ground. Aesthetically they have little in common with the traditional stone dovecotes you might find on the grounds of a manor house. The doocots I remember were monolithic towers, twenty feet tall, and they were built from salvaged materials: old Formica tabletops, screwed to corrugated iron and offcuts of MDF. It gave most doocots a rickety charm, which the men tried to disguise by painting the whole thing a uniform colour. In an afterword to Far from the Light of Heaven, Thompson asks himself if he’s writing space opera — “a conversation my editor, my agent, my cat and I had many times” — and if so, what would the tropes of that subgenre bring to his work. As a practicing psychiatrist who somehow manages another full-time career as a novelist, Thompson has shared

In an afterword to Far from the Light of Heaven, Thompson asks himself if he’s writing space opera — “a conversation my editor, my agent, my cat and I had many times” — and if so, what would the tropes of that subgenre bring to his work. As a practicing psychiatrist who somehow manages another full-time career as a novelist, Thompson has shared  A chasm divides our view of human knowledge and human nature. According to the logic of the chasm, facts are the province of experimental science, while values are the domain of religion and art; the body (and brain) is the machinery studied by scientists, while the mind is a quasi-mystical reality to be understood by direct subjective experience; reason is the faculty that produces knowledge, while emotion generates art; STEM is one kind of education, and the liberal arts are wholly other.

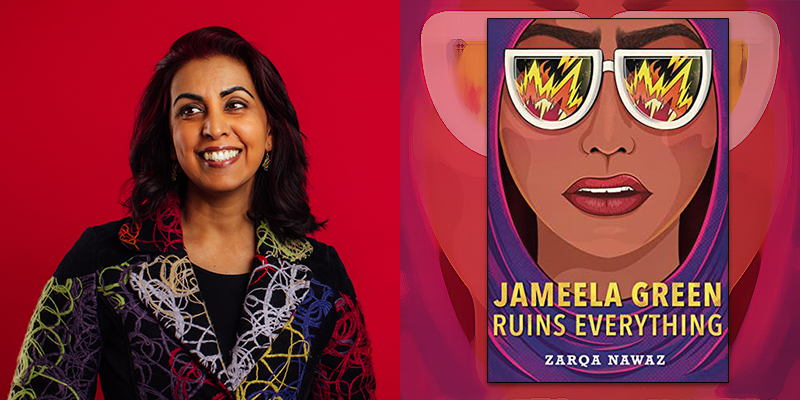

A chasm divides our view of human knowledge and human nature. According to the logic of the chasm, facts are the province of experimental science, while values are the domain of religion and art; the body (and brain) is the machinery studied by scientists, while the mind is a quasi-mystical reality to be understood by direct subjective experience; reason is the faculty that produces knowledge, while emotion generates art; STEM is one kind of education, and the liberal arts are wholly other. Zarqa Nawaz: When my memoir, Laughing All the Way to the Mosque, didn’t make it to the New York Times Best Seller list, I became a little cynical towards life. It was 2014 and ISIS had just emerged and was dominating the headlines. Muslims are forever fighting the PR war when it comes to their image. Political pundits were opining that radical Islamic jihadists were the norm in Muslim culture. I knew there was a deeper story behind ISIS, especially from the one the media was portraying. I started doing research and the novel began to emerge—a bitter writer, reeling from professional failure, gets embroiled in an ISIS like group and a series of unfortunate events ensue.

Zarqa Nawaz: When my memoir, Laughing All the Way to the Mosque, didn’t make it to the New York Times Best Seller list, I became a little cynical towards life. It was 2014 and ISIS had just emerged and was dominating the headlines. Muslims are forever fighting the PR war when it comes to their image. Political pundits were opining that radical Islamic jihadists were the norm in Muslim culture. I knew there was a deeper story behind ISIS, especially from the one the media was portraying. I started doing research and the novel began to emerge—a bitter writer, reeling from professional failure, gets embroiled in an ISIS like group and a series of unfortunate events ensue. A study looking at the economic lifetimes of 61 commercially used metals finds that more than half have a lifespan of less than 10 years. The research, published on 19 May in Nature Sustainability

A study looking at the economic lifetimes of 61 commercially used metals finds that more than half have a lifespan of less than 10 years. The research, published on 19 May in Nature Sustainability Depending on one’s pace, the season, and the ongoing state of war, it is a day’s hike from Andarab to the border of legendary Panjshir, the adjacent province in the highlands of Afghanistan. The two mountain districts, part of a five-hundred-mile-long stretch of the Hindu Kush extending from the Himalayas, are citadels that have rained doom on every bully ever to pass through Central Asia in endless dogged pursuit of cruelty and loot.

Depending on one’s pace, the season, and the ongoing state of war, it is a day’s hike from Andarab to the border of legendary Panjshir, the adjacent province in the highlands of Afghanistan. The two mountain districts, part of a five-hundred-mile-long stretch of the Hindu Kush extending from the Himalayas, are citadels that have rained doom on every bully ever to pass through Central Asia in endless dogged pursuit of cruelty and loot. May, a month we traditionally associate with spring, Mother’s Day, and graduations, was defined this year by a far different rite: funerals. In a single ten-day stretch, forty-four people were murdered in mass shootings throughout the country—a carnival of violence that confirmed, among other things, the political cowardice of a large portion of our elected leadership, the thin pretense of our moral credibility, and the sham of public displays of sympathy that translate into no actual changes in our laws, our culture, or our murderous propensities. In the two deadliest of these incidents, the oldest victim was an eighty-six-year-old grandmother, who was shot in a Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York; the youngest were nine-year-old fourth-grade students, who died in connected classrooms at Robb Elementary School, in Uvalde, Texas.

May, a month we traditionally associate with spring, Mother’s Day, and graduations, was defined this year by a far different rite: funerals. In a single ten-day stretch, forty-four people were murdered in mass shootings throughout the country—a carnival of violence that confirmed, among other things, the political cowardice of a large portion of our elected leadership, the thin pretense of our moral credibility, and the sham of public displays of sympathy that translate into no actual changes in our laws, our culture, or our murderous propensities. In the two deadliest of these incidents, the oldest victim was an eighty-six-year-old grandmother, who was shot in a Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York; the youngest were nine-year-old fourth-grade students, who died in connected classrooms at Robb Elementary School, in Uvalde, Texas. In a sense, writing a book is easy. You just keep putting one interesting sentence after another, then thread them all together along a more or less fine narrative line. Only, it isn’t easy – in fact, it’s famously difficult, a daunting and arduous labour that can frequently leave you in a state of utter nervous exhaustion, reaching for the bottle or the pills. Since his creative breakthrough with

In a sense, writing a book is easy. You just keep putting one interesting sentence after another, then thread them all together along a more or less fine narrative line. Only, it isn’t easy – in fact, it’s famously difficult, a daunting and arduous labour that can frequently leave you in a state of utter nervous exhaustion, reaching for the bottle or the pills. Since his creative breakthrough with