Raghavendra Gadagkar in Inference:

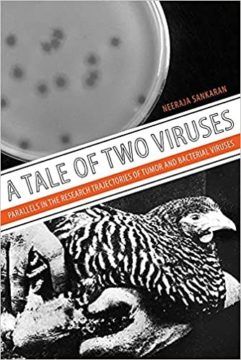

I SPENT THE SECOND HALF of the 1970s at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru immersed in studying the lysogenic mycobacteriophage I3. One floor below my laboratory, a close friend, Arun Srivastava, was studying the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV). We were both fascinated by animal and bacterial viruses, and spent our spare time reading every publication we could find about λ, T4, ΦX174, rinderpest, and Newcastle disease. We came to believe that we knew nearly everything there was to know about them.

I SPENT THE SECOND HALF of the 1970s at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru immersed in studying the lysogenic mycobacteriophage I3. One floor below my laboratory, a close friend, Arun Srivastava, was studying the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV). We were both fascinated by animal and bacterial viruses, and spent our spare time reading every publication we could find about λ, T4, ΦX174, rinderpest, and Newcastle disease. We came to believe that we knew nearly everything there was to know about them.

We were wrong.

In A Tale of Two Viruses, Neeraja Sankaran draws parallels between the stories of the bacteriophages, a group of viruses that infect bacteria, and RSV, which infects chickens. At first glance, this might seem an odd pairing for a work of comparative history. The two viruses behave very differently: phages induce lysis, which destroys bacterial cells, while RSV builds tumors. “[T]he pairing of these two viruses might seem rather arbitrary,” she writes, but “they have shared strangely parallel histories from the time of their respective discoveries in the early decades of the twentieth century until the early 1960s.”

In 1910, Peyton Rous, an American pathologist working at Rockefeller University in New York, observed that a highly filtered sarcoma extract from one test subject—a chicken, of course—could induce a sarcoma in a second test subject. He concluded correctly that, given the size of his filters, whatever the substance inducing the sarcoma, it could not have been a bacterium. It was for this work that he won the Nobel Prize almost half a century later. In 1915, Frederick Twort, a medical researcher in London, arrived at a similar conclusion with respect to substances that seemed to infect bacteria; in 1917, Félix d’Hérelle, a self-taught scientist working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, announced the discovery of “an invisible, antagonistic microbe of the dysentery bacillus.” Both men had discovered the bacteriophages.

More here.

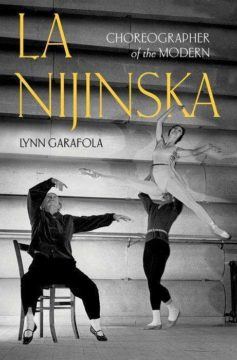

Bronislava Nijinska looked a lot like her brother, the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. This proved an advantage to her own career, and a disadvantage. They’d grown up together, studied at the Imperial Ballet school in St. Petersburg, and begun their performing careers in the Maryinsky Theater. Both were trained in the virtuosic skills of the time. Acclaimed as a prodigy from the first, Vaslav left the home company soon after graduation to join Serge Diaghilev, founder of what became the legendary Ballets Russes. Vaslav’s story—his relationship with Diaghilev, his meteoric stardom in the early ballets of Michel Fokine, his budding choreographic career fostered by the possessive Diaghilev, his expulsion from the company following his marriage to Romola de Pulzsky, and his long mental deterioration—has been told many times. It’s only a sideline in Lynn Garafola’s new book La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern.

Bronislava Nijinska looked a lot like her brother, the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. This proved an advantage to her own career, and a disadvantage. They’d grown up together, studied at the Imperial Ballet school in St. Petersburg, and begun their performing careers in the Maryinsky Theater. Both were trained in the virtuosic skills of the time. Acclaimed as a prodigy from the first, Vaslav left the home company soon after graduation to join Serge Diaghilev, founder of what became the legendary Ballets Russes. Vaslav’s story—his relationship with Diaghilev, his meteoric stardom in the early ballets of Michel Fokine, his budding choreographic career fostered by the possessive Diaghilev, his expulsion from the company following his marriage to Romola de Pulzsky, and his long mental deterioration—has been told many times. It’s only a sideline in Lynn Garafola’s new book La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern. Wispy, thick, swirled and streaking, the dark lines burst outward, racing or splintering. The strongest impression one is left with while paging through this exquisitely produced volume of Kafka’s complete drawings is of minimally delineated figures in states of maximally dramatised unrest.

Wispy, thick, swirled and streaking, the dark lines burst outward, racing or splintering. The strongest impression one is left with while paging through this exquisitely produced volume of Kafka’s complete drawings is of minimally delineated figures in states of maximally dramatised unrest. Living as I do, mostly by choice, in a post-Babel cacophony of languages, I find I often discern meanings that are not really there. This is particularly easy to do in the contact zones of the former Angevin Empire, where more than a millennium’s worth of cross-hybridity between English and French has brought it about that this empire’s ruins are populated principally by faux amis, so that one must not so much learn new words, as reconceive words one already knows. Thus deception becomes disappointment, to assist is not to help but only to be present, to report is to postpone, to defend is to prohibit (sometimes), to verbalise is to fine, to sense is to smell, to mount is to get in, to descend is to get out, a location is a rental, ice-cream has a perfume instead of a flavor, and so on.

Living as I do, mostly by choice, in a post-Babel cacophony of languages, I find I often discern meanings that are not really there. This is particularly easy to do in the contact zones of the former Angevin Empire, where more than a millennium’s worth of cross-hybridity between English and French has brought it about that this empire’s ruins are populated principally by faux amis, so that one must not so much learn new words, as reconceive words one already knows. Thus deception becomes disappointment, to assist is not to help but only to be present, to report is to postpone, to defend is to prohibit (sometimes), to verbalise is to fine, to sense is to smell, to mount is to get in, to descend is to get out, a location is a rental, ice-cream has a perfume instead of a flavor, and so on. Every now and then engineers make an advance, and scientists and lay people begin to ponder the question of whether that advance might yield important insight into the human mind. Descartes wondered whether the mind might work on hydraulic principles; throughout the second half of the 20th century, many wondered whether the digital computer would offer a

Every now and then engineers make an advance, and scientists and lay people begin to ponder the question of whether that advance might yield important insight into the human mind. Descartes wondered whether the mind might work on hydraulic principles; throughout the second half of the 20th century, many wondered whether the digital computer would offer a  In May 1959, DF Karaka, the founder editor of The Current, wrote a letter to then Finance Minister Moraji Desai about a book. Karaka explained that the book glorified a sexual relationship between a grown man and a teenage girl. He included a clipping from The Current that demanded an immediate ban on the “obscene” book.

In May 1959, DF Karaka, the founder editor of The Current, wrote a letter to then Finance Minister Moraji Desai about a book. Karaka explained that the book glorified a sexual relationship between a grown man and a teenage girl. He included a clipping from The Current that demanded an immediate ban on the “obscene” book. There’s always something relevant in clichés. If you think about it, every literary genre is a collection of clichés and commonplaces. It’s a system of expectations. The way events unfold in a fairy tale would be unacceptable in a noir novel or a science fiction story. Causal links are, to a great extent, predictable in each one of these genres. They are supposed to be predictable—even in their surprises. This is how we come to accept the reality of these worlds. And it’s so much fun to subvert those assumptions and clichés rather than to simply dismiss them, writing with one’s back turned to tradition. I should also say that these conventions usually have a heavy political load. Whenever something has calcified into a commonplace—as is the case with New York around the years of the boom and the crash—I think there is fascinating work to be done. Additionally, when I looked at the fossilized narratives from that period, I was surprised to find a void at their center: money. Even though, for obvious reasons, money is at the core of the American literature from that period, it remains a taboo—largely unquestioned and unexplored. I was unable to find many novels that talked about wealth and power in ways that were interesting to me. Class? Sure. Exploitation? Absolutely. Money? Not so much. And how bizarre is it that even though money has an almost transcendental quality in our culture it remains comparatively invisible in our literature?

There’s always something relevant in clichés. If you think about it, every literary genre is a collection of clichés and commonplaces. It’s a system of expectations. The way events unfold in a fairy tale would be unacceptable in a noir novel or a science fiction story. Causal links are, to a great extent, predictable in each one of these genres. They are supposed to be predictable—even in their surprises. This is how we come to accept the reality of these worlds. And it’s so much fun to subvert those assumptions and clichés rather than to simply dismiss them, writing with one’s back turned to tradition. I should also say that these conventions usually have a heavy political load. Whenever something has calcified into a commonplace—as is the case with New York around the years of the boom and the crash—I think there is fascinating work to be done. Additionally, when I looked at the fossilized narratives from that period, I was surprised to find a void at their center: money. Even though, for obvious reasons, money is at the core of the American literature from that period, it remains a taboo—largely unquestioned and unexplored. I was unable to find many novels that talked about wealth and power in ways that were interesting to me. Class? Sure. Exploitation? Absolutely. Money? Not so much. And how bizarre is it that even though money has an almost transcendental quality in our culture it remains comparatively invisible in our literature? In the parking areas, the drivers nestle their trucks in tightly packed rows. Their cabs function as kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices. At night, drivers can be seen through their windshields — eating dinner or reclining in their bunks, bathed in the light of a Nintendo Switch or FaceTime call home.

In the parking areas, the drivers nestle their trucks in tightly packed rows. Their cabs function as kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices. At night, drivers can be seen through their windshields — eating dinner or reclining in their bunks, bathed in the light of a Nintendo Switch or FaceTime call home. In March, Guy Reffitt, a supporter of the far-right militia group the Texas Three Percenters, became the first person convicted at trial for playing a role in the January 6, 2021,

In March, Guy Reffitt, a supporter of the far-right militia group the Texas Three Percenters, became the first person convicted at trial for playing a role in the January 6, 2021,  Francis Fukuyama is easily one of the most influential political thinkers of the last several decades.

Francis Fukuyama is easily one of the most influential political thinkers of the last several decades. Nietzsche’s protest that one cannot cleave to a moral system originating in Christianity after denying the Christian God has implications far more profound than appear at first blush. Nietzsche could already see that purportedly secular doctrines in the ascendancy in his time, and which looked set to become orthodoxy – the sanctity and inherent dignity of human life, the fundamental equality of human lives – were in their origin and character inescapably Christian. It was an absurdity, he felt, that people should, at the moment of the “death of God”, cleave all the more fiercely to the doctrines which depended on Him; or to imagine that one could keep and could promote the gamut of Christian virtues – lovingkindness, humility, charity, counsels of gentleness or forgiveness – when the religious-metaphysical belief system underpinning them had been renounced. If one gives up the God, one ought also, or must also, for the sake of what Nietzsche called one’s intellectual conscience, give up the teachings of the religion. In this Nietzsche foresaw the coming orthodoxy of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: secularised Christianity that calls itself by the names of humanism, egalitarianism, human rights, and which (quite unknowingly) preaches Christianity without Christ.

Nietzsche’s protest that one cannot cleave to a moral system originating in Christianity after denying the Christian God has implications far more profound than appear at first blush. Nietzsche could already see that purportedly secular doctrines in the ascendancy in his time, and which looked set to become orthodoxy – the sanctity and inherent dignity of human life, the fundamental equality of human lives – were in their origin and character inescapably Christian. It was an absurdity, he felt, that people should, at the moment of the “death of God”, cleave all the more fiercely to the doctrines which depended on Him; or to imagine that one could keep and could promote the gamut of Christian virtues – lovingkindness, humility, charity, counsels of gentleness or forgiveness – when the religious-metaphysical belief system underpinning them had been renounced. If one gives up the God, one ought also, or must also, for the sake of what Nietzsche called one’s intellectual conscience, give up the teachings of the religion. In this Nietzsche foresaw the coming orthodoxy of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: secularised Christianity that calls itself by the names of humanism, egalitarianism, human rights, and which (quite unknowingly) preaches Christianity without Christ. Artworks are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear.

Artworks are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear. Every so often stories of

Every so often stories of  Robert P. George: The current situation is one in which people in general—including people on college campuses, not only students, but faculty, not only untenured (and therefore, in a certain sense, insecure) faculty, but tenured faculty who are secure—are censoring themselves. All the studies that have been done on this subject reveal that people are not saying what they truly believe, or not raising certain questions they’d like to ask, because they fear the social or professional consequences of “saying the wrong thing,” or saying the right thing in “the wrong” way. Well, this, in my opinion, is terrible for institutions of higher learning, colleges and universities. It makes it impossible for us to prosecute our fundamental mission, the mission of pursuing knowledge of truth, but it’s also terrible for a democratic republic.

Robert P. George: The current situation is one in which people in general—including people on college campuses, not only students, but faculty, not only untenured (and therefore, in a certain sense, insecure) faculty, but tenured faculty who are secure—are censoring themselves. All the studies that have been done on this subject reveal that people are not saying what they truly believe, or not raising certain questions they’d like to ask, because they fear the social or professional consequences of “saying the wrong thing,” or saying the right thing in “the wrong” way. Well, this, in my opinion, is terrible for institutions of higher learning, colleges and universities. It makes it impossible for us to prosecute our fundamental mission, the mission of pursuing knowledge of truth, but it’s also terrible for a democratic republic.

I

I In an interview with the Guardian, filmmaker John Waters — creator of cult classics “Pink Flamingoes” and “Female Trouble” — lamented the rise of

In an interview with the Guardian, filmmaker John Waters — creator of cult classics “Pink Flamingoes” and “Female Trouble” — lamented the rise of