Category: Archives

Ronnie Hawkins (1935 – 2022) Rock And Roll Legend

Heddy Honigmann (1951 – 2022) Director And Documentarian

Saturday, June 4, 2022

These Data Nerds Think They’ve Found the Climate Silver Bullet: Nonvoting Environmentalists

Liza Featherstone in The New Republic:

Liza Featherstone in The New Republic:

Voters don’t care enough about climate, according to conventional wisdom. The best way to address climate change is for Democrats to win elections by talking about other subjects, consultants say. The problem with this political advice is that Democratic politicians, acting on the insight that voters don’t care, get into office and then don’t set a high priority on climate policy—because they want to be reelected.

Put this way, it sounds like we have an almost unsolvable problem on our hands, one that could lead us to believe that representative democracy was incompatible with human survival. Conversations with liberals and progressives these days, especially those engaged in climate issues, are unfailingly gloomy. The right seems to be on a winning streak; relatedly, we’re all doomed. But what if there was a way out of this existential cul-de-sac?

The data nerds and activists behind the Environmental Voter Project, or EVP, think there is. They’ve got extensive research and proven results to support this crazy bit of optimism, and they’re using it to try to sway the midterms, a looming political event that most liberals are hailing with unqualified despair.

More here.

Paraphrase me if you dare

Colin Burrow on Stanley Cavell’s Here and There in the LRB:

Colin Burrow on Stanley Cavell’s Here and There in the LRB:

When I was small we were sometimes visited by a moral philosopher. He always outstayed his welcome, and did many things which non-philosophers might regard as immoral or selfish, some of them more forgivable than others (I have forgiven him for confiscating the rubber ball that I enjoyed bouncing around the hall, but not for destroying it). Whenever my mother went to rebuke him for his misdeeds she would find him standing on his head, with his feet clad in purple socks, reciting over and over again the mantra: ‘Only I can feel my pain.’ It was, she would say, hard to address a pair of purple socks as though they were a moral agent.

Our unwelcome guest was one of the many enthusiastic followers of Wittgenstein in the 1960s and 1970s, and his meditations were no doubt intended to draw him into a deeper understanding of the discussions of pain and private language in the Philosophical Investigations. In the 1980s at Cambridge I was taught by a generation of critics who had developed a radically conservative aesthetics from a fusion of Wittgenstein’s writing on language and J.L. Austin’s on speech acts. Wittgenstein suggested that we could only say someone had grasped the rules of chess when they could offer a ‘criterion’ of having done so, by being able to make the right moves. In lectures I heard that claim developed into an argument to the effect that there were no mute inglorious Miltons out there, because the only criterion of having a beautifully complex thought was the ability to write in a beautiful and complex way.

More here.

General Theories

Nina Eichacker in Phenomenal World:

Nina Eichacker in Phenomenal World:

In 2022, the audience for books about John Maynard Keynes is probably as large as it has ever been. With two global economic crises followed by widespread use of government interventions, debates recently relegated to history books and academic journals have acquired new urgency. The curious reader can pick from a wealth of recent books. Geoff Mann’s In the Long Run We Are All Dead: Keynesianism, Political Economy, and Revolution (2017) and heterodox economist James Crotty’s Keynes Against Capitalism: His Economic Case for Liberal Socialism (2019) offer perspectives from critical political economy, while Zach Carter’s The Price of Peace: Money, Democracy, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes (2020) presents a detailed biography. But until now, there has been nothing quite like Stephen Marglin’s Raising Keynes, which subtly promises no less than A Twenty-first Century General Theory. The text runs to more than 896 pages, weighs four pounds in hardcover, and, as Marglin acknowledges, is not an easy read. But the result is truly original.

Marglin is uniquely positioned to carry forward the trajectory of the Keynesian tradition. Like Keynes, Marglin’s early career saw him transform from the star pupil of the reigning economic theories of his training—neoclassical economics—into a sort of a radical economist of his own category after receiving tenure. And, like Keynes, Marglin argues that it was his observation of the world around him that forced him to shed his allegiance to neoclassical theories and their claim to represent how the world works.

More here.

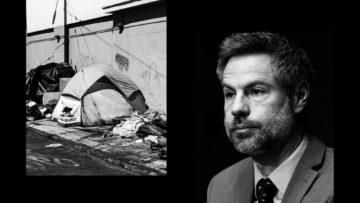

The Revolt Against Homelessness

Olga Khazan in The Atlantic:

SAN FRANCISCO—Michael Shellenberger was more excited to tour the Tenderloin than I was, even though it was my idea. I was nervous about provoking desperate people in various states of disrepair. Shellenberger, meanwhile, seemed intent on showing that many homeless people are addicted to drugs. (If that seems callous to you, Shellenberger would say you’re in thrall to liberal “victim ideology.”) He told me not to worry. “You seem like a tough Russian chick, right?” he said as we walked up narrow sidewalks where hundreds of humans sleep at night, passing people sitting on wheelchairs, under tarps, and in tents. Many were slumped over or nodding off—from fentanyl, Shellenberger said. One man walked down the street hooting repeatedly to no one.

SAN FRANCISCO—Michael Shellenberger was more excited to tour the Tenderloin than I was, even though it was my idea. I was nervous about provoking desperate people in various states of disrepair. Shellenberger, meanwhile, seemed intent on showing that many homeless people are addicted to drugs. (If that seems callous to you, Shellenberger would say you’re in thrall to liberal “victim ideology.”) He told me not to worry. “You seem like a tough Russian chick, right?” he said as we walked up narrow sidewalks where hundreds of humans sleep at night, passing people sitting on wheelchairs, under tarps, and in tents. Many were slumped over or nodding off—from fentanyl, Shellenberger said. One man walked down the street hooting repeatedly to no one.

As we talked with people, Shellenberger kept introducing himself as a “reporter,” even though he’s running for governor of California. His candidacy has indeed involved a lot of interviewing: He often films himself asking homeless people about their lives and tweets about it. He has also written several books, including last year’s San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities, which makes the argument that has become a central plank of his candidacy: What most homeless people need is not, in his words, “namby pamby” TLC from lefty nonprofits but a firm hand and a stint in rehab. He’s essentially a single-issue candidate running against homelessness and its consequences. Fortunately for him, that’s an issue Californians feel strongly about. And thanks to California’s top-two “jungle” primary system, there’s a chance he could make it past the June 7 primary and face off against California Governor Gavin Newsom in the general election.

More here.

“We’re losing the war against disinformation”: This American Life’s Ira Glass

Harry Clarke-Ezzidio in New Stateman:

Ira Glass worked through and missed our scheduled Zoom interview. “It’s really just been like a normal work week, but I just didn’t manage it as ideally as I could have,” he told me, apologetically, when we chat a few days later. He missed the call because that week’s episode of This American Life, the podcast and radio show he founded in 1995 and still hosts today, had to be completely re-edited and recorded. “Stuff just has to get done… it gets very complicated.”

Ira Glass worked through and missed our scheduled Zoom interview. “It’s really just been like a normal work week, but I just didn’t manage it as ideally as I could have,” he told me, apologetically, when we chat a few days later. He missed the call because that week’s episode of This American Life, the podcast and radio show he founded in 1995 and still hosts today, had to be completely re-edited and recorded. “Stuff just has to get done… it gets very complicated.”

Glass seems to be spinning a number of plates at any given time. This American Life has a wide remit and, despite its name, a global focus; telling stories in “acts” centred around a weekly theme, the show covers everything from the most inane and granular aspects of life to more existential issues including elections and protests. The programme attracts around four million listeners every week.

We spoke a few weeks after Glass, who lives in New York, came to London’s Southbank Centre in March to perform Seven Things I’ve Learned, his one-man show, delayed due to the pandemic. “I have Covid that I got in London,” he declared at the beginning of the call. “Nobody here wears a mask at all!” he previously joked to the London audience. “A British friend and I talked about this before my girlfriend and I came, and I was like, ‘OK, so what are our chances of me getting some mild case of Covid? Are they 100 per cent or 90 per cent?’”

More here.

Nell Zink Discusses Things

Lisa Borst interviews Nell Zink at Bookforum:

I was reading the kinds of essays, in German, that academics write about the kinds of things that Peter is obsessed with. But my big reading event of that period was the diaries of Victor Klemperer—one of the great reading experiences of my life. It’s like if Proust were not about venal parties. It’s nonfiction, and takes place from 1933 to 1945 in Germany, from the point of view of a middle-age Jewish intellectual who survived it all out in the open, because he had a so-called Aryan wife who stood by him. He lived without having to go to a camp. And it’s so incredibly moving, because it’s a diary, so as he’s writing it, he doesn’t know what’s going to happen. There are constant bits like, Hitler’s going to get voted out. He’s going to lose the war. Everybody secretly hates him, nobody takes this guy seriously. The Americans will be here next week. It’s the most magnificent book.

I was reading the kinds of essays, in German, that academics write about the kinds of things that Peter is obsessed with. But my big reading event of that period was the diaries of Victor Klemperer—one of the great reading experiences of my life. It’s like if Proust were not about venal parties. It’s nonfiction, and takes place from 1933 to 1945 in Germany, from the point of view of a middle-age Jewish intellectual who survived it all out in the open, because he had a so-called Aryan wife who stood by him. He lived without having to go to a camp. And it’s so incredibly moving, because it’s a diary, so as he’s writing it, he doesn’t know what’s going to happen. There are constant bits like, Hitler’s going to get voted out. He’s going to lose the war. Everybody secretly hates him, nobody takes this guy seriously. The Americans will be here next week. It’s the most magnificent book.

Because of that, I had it on the brain that it’s possible for a book to be truly good. And, not being Victor Klemperer, I thought—well, it’s not like he’s such a great writer, but he was unbelievably brave to do it at all, and his wife was unbelievably brave to smuggle his diary pages across town for safekeeping. Everybody was brave as shit to make this book exist. It makes you think writing books is not a complete waste of time, which is always a good starting point.

more here.

Nell Zink Presents “Avalon,” With Emily Gould

Atoms and Ashes by Serhii Plokhy

Robin McKie at The Guardian:

Once hailed as a source of electricity that would be too cheap to meter, atomic power has come a long way since the 1950s – mostly downhill. Far from being cost-free, nuclear-generated electricity is today more expensive than power produced by coal, gas, wind or solar plants while sites storing spent uranium and irradiated equipment litter the globe, a deadly radioactive legacy that will endure for hundreds of thousands of years. For good measure, most analysts now accept that the spread of atomic energy played a crucial role in driving nuclear weapon proliferation.

Once hailed as a source of electricity that would be too cheap to meter, atomic power has come a long way since the 1950s – mostly downhill. Far from being cost-free, nuclear-generated electricity is today more expensive than power produced by coal, gas, wind or solar plants while sites storing spent uranium and irradiated equipment litter the globe, a deadly radioactive legacy that will endure for hundreds of thousands of years. For good measure, most analysts now accept that the spread of atomic energy played a crucial role in driving nuclear weapon proliferation.

Then there are the disasters. Some of the world’s worst accidents have had nuclear origins and half a dozen especially egregious examples have been selected by Harvard historian Serhii Plokhy to support his thesis that atomic power is never going to be the energy saviour of our imperilled species.

more here.

Friday, June 3, 2022

The big idea: could the greatest works of literature be undiscovered?

Laura Spinney in The Guardian:

When the great library at Alexandria went up in flames, it is said that the books took six months to burn. We can’t know if this is true. Exactly how the library met its end, and whether it even existed, have been subjects of speculation for more than 2,000 years. For two millennia, we’ve been haunted by the idea that what has been passed down to us might not be representative of the vast corpus of literature and knowledge that humans have created. It’s a fear that has only been confirmed by new methods for estimating the extent of the losses.

When the great library at Alexandria went up in flames, it is said that the books took six months to burn. We can’t know if this is true. Exactly how the library met its end, and whether it even existed, have been subjects of speculation for more than 2,000 years. For two millennia, we’ve been haunted by the idea that what has been passed down to us might not be representative of the vast corpus of literature and knowledge that humans have created. It’s a fear that has only been confirmed by new methods for estimating the extent of the losses.

The latest attempt was led by scholars Mike Kestemont and Folgert Karsdorp. The Ptolemies who created the library at Alexandria had a suitably pharaonic vision: to bring every book that had ever been written under one roof. Kestemont and Karsdorp had a more modest goal – to estimate the survival rate of manuscripts created in different parts of Europe during the middle ages.

Using a statistical method borrowed from ecology, called “unseen species” modelling, they extrapolated from what has survived to gauge how much hasn’t – working backwards from the distribution of manuscripts we have today in order to estimate what must have existed in the past. The numbers they published in Science magazine earlier this year don’t make for happy reading, but they corroborate figures arrived at by other methods. The researchers concluded that a humbling 90% of medieval manuscripts preserving chivalric and heroic narratives – those relating to King Arthur, for example, or Sigurd (also known as Siegfried) – have gone.

More here.

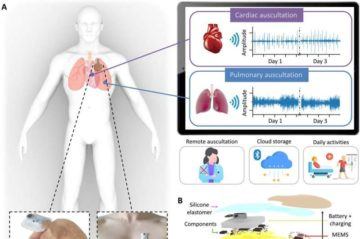

A soft wearable stethoscope designed for automated remote disease diagnosis

From Phys.Org:

Digital stethoscopes provide better results compared to conventional methods to record and visualize modern auscultation. Current stethoscopes are bulky, non-conformal, and not suited for remote use, while motion artifacts can lead to inaccurate diagnosis. In a new report now published in Science Advances, Sung Hoon Lee and a research team in engineering, nanotechnology, and medicine at the Georgia Institute of Technology, U.S., and the Chungnam National University Hospital in the Republic of Korea described a class of methods to offer real-time, wireless, continuous auscultation. The devices are part of a soft wearable system for quantitative disease diagnosis across various pathologies. Using the soft device, Lee et al detected continuous cardiopulmonary sounds with minimal noise to characterize signal abnormalities in real-time.

Digital stethoscopes provide better results compared to conventional methods to record and visualize modern auscultation. Current stethoscopes are bulky, non-conformal, and not suited for remote use, while motion artifacts can lead to inaccurate diagnosis. In a new report now published in Science Advances, Sung Hoon Lee and a research team in engineering, nanotechnology, and medicine at the Georgia Institute of Technology, U.S., and the Chungnam National University Hospital in the Republic of Korea described a class of methods to offer real-time, wireless, continuous auscultation. The devices are part of a soft wearable system for quantitative disease diagnosis across various pathologies. Using the soft device, Lee et al detected continuous cardiopulmonary sounds with minimal noise to characterize signal abnormalities in real-time.

The team conducted a clinical study with multiple patients and control subjects to understand the unique advantage of the wearable auscultation method, with integrated machine learning, to automate diagnoses of four types of disease in the lung, ranging from a crackle, to a wheeze, stridor and rhonchi, with 95% accuracy. The soft system is applicable for a sleep study to detect disordered breathing and to detect sleep apnea.

More here.

What is Time? Emily Thomas speaks with Justin E. H. Smith

From The Point:

In this episode of “What Is X?” Justin E.H. Smith and Emily Thomas tackle the timely yet timeless question: “What is time?” Is time an external, objective fact, or is the flow and tempo of the world internal to us—in some sense, all in our head? Could a robot have consciousness even if it didn’t understand time?

More here.

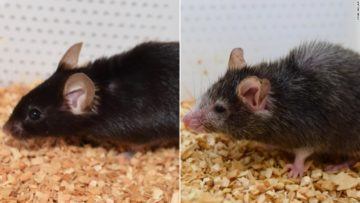

The ‘Benjamin Button’ effect: Scientists can reverse aging in mice

Sandee LaMotte at CNN:

In molecular biologist David Sinclair’s lab at Harvard Medical School, old mice are growing young again.

In molecular biologist David Sinclair’s lab at Harvard Medical School, old mice are growing young again.

Using proteins that can turn an adult cell into a stem cell, Sinclair and his team have reset aging cells in mice to earlier versions of themselves. In his team’s first breakthrough, published in late 2020, old mice with poor eyesight and damaged retinas could suddenly see again, with vision that at times rivaled their offspring’s.

“It’s a permanent reset, as far as we can tell, and we think it may be a universal process that could be applied across the body to reset our age,” said Sinclair, who has spent the last 20 years studying ways to reverse the ravages of time.

“If we reverse aging, these diseases should not happen. We have the technology today to be able to go into your hundreds without worrying about getting cancer in your 70s, heart disease in your 80s and Alzheimer’s in your 90s.” Sinclair told an audience at Life Itself, a health and wellness event presented in partnership with CNN.

“This is the world that is coming. It’s literally a question of when and for most of us, it’s going to happen in our lifetimes,” Sinclair told the audience.

More here.

Hugh Laurie Reads The 57 “Thank You” Notes He Mailed To Stephen Colbert

Why the “Bad Gays” of History Deserve More Attention

Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller in Literary Hub:

In 1891, Oscar Wilde’s star was on the rise. For a decade he had been the talk of London, a literary wit who pioneered the fashion and philosophy of aestheticism. He had successfully published works of prose and collections of poetry, and was preparing his first novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, for publication, a masterful account of a Faustian bargain dripping with desire, vanity, and corruption. England regarded this sparkling Irishman with a combination of fascination, admiration, and horror, but no one could deny he was becoming a titan of the national culture.

Yet within five years, Wilde’s reputation, and his health, were destroyed. Sentenced to two years of backbreaking hard labor, Wilde was spat at by strangers as he was transported via train to jail. Upon release, he fled into exile, living in penury under an assumed name. Nobody wanted to be known as his friend. Less than a decade after he had reached the heights of literary stardom, Wilde was dead.

It’s right and proper that we remember the role Wilde played within an otherwise staid and repressive Victorian culture, as well as the important, pioneering work he did describing, in public, a form of same-sex desire that otherwise lay hidden and criminalized on the margins.

More here.

In Our Time: The Davidian Revolution

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Od-HUxuUSno&ab_channel=InOurTime

A Dictator and His Books

Gary Saul Morson at The New Criterion:

When the novelist Mikhail Sholokhov, who later won the Nobel Prize for literature, had trouble getting the third part of The Quiet Don approved for publication, he appealed to Maxim Gorky, then the supreme authority in Soviet literary affairs. Gorky invited him to his mansion, which had been a gift from Stalin to lure Gorky home from self-imposed exile. When Sholokhov arrived, he discovered that Gorky had company: Stalin himself.

When the novelist Mikhail Sholokhov, who later won the Nobel Prize for literature, had trouble getting the third part of The Quiet Don approved for publication, he appealed to Maxim Gorky, then the supreme authority in Soviet literary affairs. Gorky invited him to his mansion, which had been a gift from Stalin to lure Gorky home from self-imposed exile. When Sholokhov arrived, he discovered that Gorky had company: Stalin himself.

Stalin interrogated Sholokhov about ideologically problematic passages but agreed to the book’s publication on condition that Sholokhov also write a novel glorifying the Soviet collectivization of agriculture. Still more important, he gave Sholokhov a piece of paper explaining how to contact Stalin’s personal secretary, Aleksandr Poskrebyshev, and providing the number of his direct phone line.

more here.

Rachel Carson’s Epic

Dean Flower at The Hudson Review:

Perhaps the most Melvillean chapter of The Sea Around Us is “Wind and Water,” which goes into fascinating detail about how winds (and volcanoes) create waves (and tsunamis), how many thousands of miles they travel, how each one is measured (five hundred miles of fetch!), and what destruction the largest of them can cause, especially when they come ashore “armed with stones and rock fragments.” Maritime history is replete with legends of gigantic waves, many of which can sound apocryphal, but Carson’s information about waves in excess of 60 feet is relentlessly persuasive. To cite only one of these, she tells of a huge wave that lifted a 135-pound rock and “hurled [it] high above the lightkeeper’s house on Tillamook Rock [in Oregon] . . . 100 feet above sea level,” smashing it to pieces. She also quotes Lord Bryce’s observation about storm surf on the coast of Tierra del Fuego, “There is not in the world a coast more terrible than this!” Charles Darwin agreed, not mincing his words: “The sight of such a coast is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about death, peril, and shipwreck.”

Perhaps the most Melvillean chapter of The Sea Around Us is “Wind and Water,” which goes into fascinating detail about how winds (and volcanoes) create waves (and tsunamis), how many thousands of miles they travel, how each one is measured (five hundred miles of fetch!), and what destruction the largest of them can cause, especially when they come ashore “armed with stones and rock fragments.” Maritime history is replete with legends of gigantic waves, many of which can sound apocryphal, but Carson’s information about waves in excess of 60 feet is relentlessly persuasive. To cite only one of these, she tells of a huge wave that lifted a 135-pound rock and “hurled [it] high above the lightkeeper’s house on Tillamook Rock [in Oregon] . . . 100 feet above sea level,” smashing it to pieces. She also quotes Lord Bryce’s observation about storm surf on the coast of Tierra del Fuego, “There is not in the world a coast more terrible than this!” Charles Darwin agreed, not mincing his words: “The sight of such a coast is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about death, peril, and shipwreck.”

more here.