Category: Archives

Monty Norman (1929 – 2022) Film Composer

Harvey Dinnerstein (1928 – 2022) Realist Painter

Sunday Poem

F this and F that

One of the fringe benefits

……………………. of turning sixteen:

…………. a boy can tell the whole world

to get fucked and fly

…………………….down the street,

…………. as if his car were on fire

and the only way to put the fire out

…………………….is driving

…………. as fast as he can.

O fuck for when he opens the letter

…………………….that says exactly

…………. what he’s afraid it would.

Go fuck yourself

…………………….for when his father tries

…………. to persuade him

nothing will be different

…………………….now that his mother’s moving out.

…………. Motherfucker for the walls

that get in the boy’s way

…………………….in the hospital

…………. where his grandpop’s dying.

Fuck. The teeth biting into

…………………….the lower lip

…………. then the ck—just as good

as spitting into someone’s face.

…………………….Nothing else will do,

…………. Just when the boy’s sure

he’ll never be able to say what he feels,

…………………….this one syllable rises

…………. out of the great silence

all words inhabit

…………………….till they’re spoken.

…………. Fucking A! It’s the

kiss of a basketball

…………………….off the backboard.

…………. A key fitting

into the door he thought

…………………….locked forever.

…………. Light in a girl’s just-washed hair.

Fucking A. Once again

…………………….words

…………. had not failed him.

by Christopher Bursk

from The First Inhabitant of Arcadia

The University of Arkansas Press, 2006

The Case Against the Trauma Plot

Parul Sehgal in The New Yorker:

t was on a train journey, from Richmond to Waterloo, that Virginia Woolf encountered the weeping woman. A pinched little thing, with her silent tears, she had no way of knowing that she was about to be enlisted into an argument about the fate of fiction. Woolf summoned her in the 1924 essay “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown,” writing that “all novels begin with an old lady in the corner opposite”—a character who awakens the imagination. Unless the English novel recalled that fact, Woolf thought, the form would be finished. Plot and originality count for crumbs if a writer cannot bring the unhappy lady to life. And here Woolf, almost helplessly, began to spin a story herself—the cottage that the old lady kept, decorated with sea urchins, her way of picking her meals off a saucer—alighting on details of odd, dark density to convey something of this woman’s essence.

t was on a train journey, from Richmond to Waterloo, that Virginia Woolf encountered the weeping woman. A pinched little thing, with her silent tears, she had no way of knowing that she was about to be enlisted into an argument about the fate of fiction. Woolf summoned her in the 1924 essay “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown,” writing that “all novels begin with an old lady in the corner opposite”—a character who awakens the imagination. Unless the English novel recalled that fact, Woolf thought, the form would be finished. Plot and originality count for crumbs if a writer cannot bring the unhappy lady to life. And here Woolf, almost helplessly, began to spin a story herself—the cottage that the old lady kept, decorated with sea urchins, her way of picking her meals off a saucer—alighting on details of odd, dark density to convey something of this woman’s essence.

Those details: the sea urchins, that saucer, that slant of personality. To conjure them, Woolf said, a writer draws from her temperament, her time, her country. An English novelist would portray the woman as an eccentric, warty and beribboned. A Russian would turn her into an untethered soul wandering the street, “asking of life some tremendous question.”

More here.

Migraine Treatment Has Come a Long Way

Melinda Moyer in The New York Times:

If you don’t suffer from migraine headaches, you probably know at least one person who does. Nearly 40 million Americans get them — 28 million of them women and girls — making migraine the second most disabling condition in the world after low back pain. Several studies have found that migraine became more frequent during the pandemic, too. I get migraine headaches, but thankfully they’re more bizarre than excruciating. Every few weeks, ocular migraine clouds my vision with strange zig-zagging lights for a half-hour; and once or twice a year I get attacks that cause temporary memory loss. (One came on while I was grocery shopping, and I couldn’t remember what month or year it was, what I was there to buy or how old my kids were.)

If you don’t suffer from migraine headaches, you probably know at least one person who does. Nearly 40 million Americans get them — 28 million of them women and girls — making migraine the second most disabling condition in the world after low back pain. Several studies have found that migraine became more frequent during the pandemic, too. I get migraine headaches, but thankfully they’re more bizarre than excruciating. Every few weeks, ocular migraine clouds my vision with strange zig-zagging lights for a half-hour; and once or twice a year I get attacks that cause temporary memory loss. (One came on while I was grocery shopping, and I couldn’t remember what month or year it was, what I was there to buy or how old my kids were.)

Despite its ubiquity, research on migraine has long been underfunded. The National Institutes of Health spent only $40 million on migraine research in 2021; by comparison, it spent $218 million researching epilepsy, which afflicts one-twelfth as many Americans. Why is this devastating condition so woefully understudied?

More here.

Saturday, July 16, 2022

Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Thomas Oatley:

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the West’s response have fractured global order. Western governments will not be able to piece the system back together. The invasion, as well as the broader foreign policy that produced it, indicate that Putin’s Russia is unwilling to continue as a subordinate member of a Western-led international order.

Debate over the West’s supposed responsibility for triggering the invasion has focused narrowly on the developing relationship between Ukraine and NATO and the extent to which this threatens Russian security. This focus has led analysts to neglect the broader question of how Putin views Russia’s place in the contemporary world order, as well as the extent to which the invasion constitutes an attempt to change this system.

Yet these broader concerns appear to play an important role in the regime’s calculations. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has commented that Russia’s invasion

is “rooted in the U.S. and West’s desire to rule the world,” and reflects a determination by Russia to create “a multipolar, just, democratic world order.”

Regardless of the outcome in Ukraine, therefore, Russia’s dissatisfaction with its subordinate status in the Liberal Order (does one peer tell another that it stands on the “wrong side of history”?) and determination to restructure it will persist. Consequently, Russia will not reintegrate into this order.

More here.

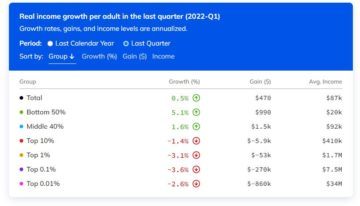

Who Benefits from Income and Wealth Growth in the United States?

Thomas Blanchet, Emmanuel Saez, Gabriel Zucman of the Department of Economics at University of California, Berkeley have created a tool to track income and wealth inequality in near real time.

Realtime Inequality provides the first timely statistics on how economic growth is distributed across groups. When new growth numbers come out each quarter, we show how each income and wealth group benefits. Controlling for price inflation, average national income per adult in the United States increased at an annualized rate of 0.5% in the first quarter of 2022, and average income for the bottom 50% grew by 5.1%. National income is similar to GDP and a better indicator of income earned by US residents. Visit the Methodology page for complete methodological details.

More here.

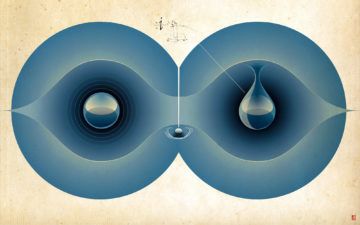

Imaginary numbers are real

Karmela Padavic-Callaghani in Aeon (Illustration by Richard Wilkinson):

Karmela Padavic-Callaghani in Aeon (Illustration by Richard Wilkinson):

Many science students may imagine a ball rolling down a hill or a car skidding because of friction as prototypical examples of the systems physicists care about. But much of modern physics consists of searching for objects and phenomena that are virtually invisible: the tiny electrons of quantum physics and the particles hidden within strange metals of materials science along with their highly energetic counterparts that only exist briefly within giant particle colliders.

In their quest to grasp these hidden building blocks of reality scientists have looked to mathematical theories and formalism. Ideally, an unexpected experimental observation leads a physicist to a new mathematical theory, and then mathematical work on said theory leads them to new experiments and new observations. Some part of this process inevitably happens in the physicist’s mind, where symbols and numbers help make invisible theoretical ideas visible in the tangible, measurable physical world.

Sometimes, however, as in the case of imaginary numbers – that is, numbers with negative square values – mathematics manages to stay ahead of experiments for a long time. Though imaginary numbers have been integral to quantum theory since its very beginnings in the 1920s, scientists have only recently been able to find their physical signatures in experiments and empirically prove their necessity.

More here.

Blake Lemoine On AI Sentience

What We Talk About When We Talk About Israel

Matti Friedman in The Atlantic:

The American Colony, where I’m writing these lines on a table in the courtyard, is one physical incarnation of the thesis of The Arc of a Covenant: The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People. Mead, a distinguished professor of foreign affairs, columnist, and author, would like to take us on a tour not of Israel but of the manifestations of Israel in the American mind—an even weirder place than the actual country where I live and report.

The American Colony, where I’m writing these lines on a table in the courtyard, is one physical incarnation of the thesis of The Arc of a Covenant: The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People. Mead, a distinguished professor of foreign affairs, columnist, and author, would like to take us on a tour not of Israel but of the manifestations of Israel in the American mind—an even weirder place than the actual country where I live and report.

The American fascination with Israel and with Jews, Mead believes, is not driven primarily by Israel or real Jews. Instead, “Israel” is a political instrument or a way of thinking about unrelated problems, just as those American settlers of the 1800s believed the Jews might serve as tools in a Christian end-times drama. The “idea that the Jews would return to the lands of the Bible and build a state there,” Mead writes, “touches on some of the most powerful themes and cherished hopes of American religion and culture.” And today, too, America’s furious debates about Israel policy have other homespun sources, and are more about conflicts over “American identity, the direction of world politics, and the place that the United States should aspire to occupy in world history than about anything that real-world Israelis and Palestinians may happen to be doing at any particular time.”

In that vein, Mead leads us with an even tone and expert hand through centuries of history, and through disparate topics including Puritan theology, the politics at the court of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the personality of Billy Graham. Eleanor Roosevelt’s support for the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, we learn, was primarily a way of supporting a new “liberal order” after World War II. Growing Republican Party backing for Israel beginning in the 1970s was thanks not to any Jewish lobby but to the party’s understanding that this was an issue that could unite a fractious coalition of “pious evangelicals, honky-tonking southern good ol’ boys, blue-collar Midwestern Catholics, and elite neoconservative policy intellectuals”—just as today, hostility toward Israel is a way to mobilize a progressive movement that wants to somehow embrace both Dearborn and the Dyke March. For millions of American Christians in the late 1800s, a Jewish return to Zion was less about helping Jews than about proving the truth of biblical prophecy in a country where many seemed to be losing their religion.

More here.

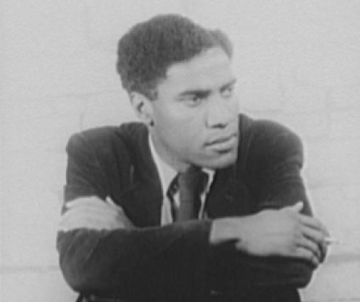

George Lamming (1927–2022)

John Plotz at Public Books:

The epigraph to In the Castle of My Skin (“Something startles where I thought I was safe”) comes from Walt Whitman. Lamming takes heart from Whitman’s embrace of the sometimes paradoxical multiplicity that comes with giving one another room, with hearing and assimilating others’ viewpoints: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes).” There is even a subtle lesson in the names of Lamming’s first and last novels. As phrases, both In the Castle of My Skin and Natives of My Person allude to the complex interior state of the speaker. Both configure that interior as a populous place, shot through with other voices, other lives.

The epigraph to In the Castle of My Skin (“Something startles where I thought I was safe”) comes from Walt Whitman. Lamming takes heart from Whitman’s embrace of the sometimes paradoxical multiplicity that comes with giving one another room, with hearing and assimilating others’ viewpoints: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes).” There is even a subtle lesson in the names of Lamming’s first and last novels. As phrases, both In the Castle of My Skin and Natives of My Person allude to the complex interior state of the speaker. Both configure that interior as a populous place, shot through with other voices, other lives.

Natives of My Person, a torqued retelling of the post-Columbus era of European exploration and land grabs, concludes with a poignant scene between the wives of characters who have staked their lives on a mad venture westward.

more here.

Taking the Magic Out of Magic Mushrooms

Dana Smith in The New York Times:

Nick Fernandez was in hell — one filled with fire and skulls and the long-legged elephants from a Salvador Dalí painting. A spirit had guided him there after his funeral; other stops on their journey included Grand Central Terminal, the top of the Empire State Building and the sewers flowing beneath New York City. Their final destination was a cave where Mr. Fernandez encountered his own body, hung up on a clothes hanger. By examining his body in this way, he was able to come to peace with all that it had been through and accept it as his own.

Nick Fernandez was in hell — one filled with fire and skulls and the long-legged elephants from a Salvador Dalí painting. A spirit had guided him there after his funeral; other stops on their journey included Grand Central Terminal, the top of the Empire State Building and the sewers flowing beneath New York City. Their final destination was a cave where Mr. Fernandez encountered his own body, hung up on a clothes hanger. By examining his body in this way, he was able to come to peace with all that it had been through and accept it as his own.

Mr. Fernandez was tripping on a very large dose of psilocybin, the psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms. He took the drug as part of a clinical trial at New York University for people dealing with anxiety and depression following a cancer diagnosis. That study and several others have found that psychedelic drugs like psilocybin are remarkably good at alleviating symptoms of depression and anxiety — even in many people who do not respond to currently prescribed medications. They need to be taken only a few times (most clinical trials consist of two or three psychedelic sessions) instead of daily for months or years. Some experts say the therapy could be thought of as a surgery that solves a problem with a single procedure instead of a continuing treatment to manage a chronic condition.

More here.

‘Carnality,’ by Lina Wolff

Molly Young at the New York Times:

“Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life.

“Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life.

Premise established, we are safely buckled in for the ride, which rumbles along a scenic track for roughly five minutes before a crazed carnival operator assumes the controls and we take off at warp speed through loops, inversions and spins. The third-person narration turns into a monologue from a secondary character, which morphs into a memoir in the form of letters from a third character.

more here.

Saturday Poem

This is a Political Poem

Three people stand in a shop in Paris looking

at an old piano. It might have been played by

Beethoven. The veneer is sumptuous, though

blistered where separated from the shaping

pieces. Inside, no cast-iron frame, but thick,

wooden struts. The woman attempts a scale, but

many of the notes are missing. “It’s like trying

to capture moonlight in a net.” The man marvels

at the piano’s age and that it had been made

entirely by hand. The shop owner tells them,

“The trees for the wood were most likely planted

in the late sixteenth century. The woodworking

guilds of Germany planted trees so their children’s

children’s children would have the right kind of wood

harvested, sometimes, 250 years later. Then it was

cured from 10 to 40 years. Even in the nineteenth century,

such wood was rare, but now it is a substance

that has gone out of the world we live in.”

by Nils Peterson

Author’s note: This poem is gathered from a few pages of Thad Carhart’s

fine book “Piano Shop on the Left Bank”.

Friday, July 15, 2022

Robert Pinsky reviews Lucasta Miller’s “Keats: A Brief Life in Nine Poems and One Epitaph”

Robert Pinsky in the New York Times:

Early in her book about John Keats, Lucasta Miller calls Lord Byron an “aristocratic megastar.” That funny epithet is accurate for Byron’s more-than-superstar celebrity in his day. It also suggests the many ways Byron was the opposite of Keats. Miller quotes Byron, in a letter, referring to the younger and much less well-known poet as “Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are.”

Early in her book about John Keats, Lucasta Miller calls Lord Byron an “aristocratic megastar.” That funny epithet is accurate for Byron’s more-than-superstar celebrity in his day. It also suggests the many ways Byron was the opposite of Keats. Miller quotes Byron, in a letter, referring to the younger and much less well-known poet as “Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are.”

Posterity, as Miller says, has since then “leveled … up” the two poets. And “leveled” is an understatement. For a certain lyrical essence of poetry written in English, Keats in his greatest poems surpasses every writer since Shakespeare. For poets, he embodies something central to the art, a little like what Shakespeare embodied for Keats. That lyrical core survives the tangle of mythology that exaggerates his actual life.

Well beyond the contrast with Byron, the words “aristocratic” and “megastar” are germane to Miller’s job of refreshing and clarifying an old story. Social class and fame were both powerful, daily presences for Keats. They still infuse the shifty cloud of half-truths, myths, stereotypes, facts and genuine marvels that surround his astonishing career.

More here.

The Lost ACLU Lecture of Carl Sagan

Steven Pinker and Harvey Silverglate in Quillette:

Around 1987, Sagan gave an uncannily prescient lecture to the Illinois state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union on the intersection between his area of expertise and theirs. We were fortunate to obtain a recording of that lecture, which we have transcribed, lightly edited, and annotated to update its historical allusions and contemporary relevance. Sagan spoke prophetically of the irrationality that plagued public discourse, the imperative of international cooperation, the dangers posed by advances in technology, and the threats to free speech and democracy in the United States. A 35-year retrospective reveals both increments of progress (some owing to Sagan’s own efforts) and

Around 1987, Sagan gave an uncannily prescient lecture to the Illinois state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union on the intersection between his area of expertise and theirs. We were fortunate to obtain a recording of that lecture, which we have transcribed, lightly edited, and annotated to update its historical allusions and contemporary relevance. Sagan spoke prophetically of the irrationality that plagued public discourse, the imperative of international cooperation, the dangers posed by advances in technology, and the threats to free speech and democracy in the United States. A 35-year retrospective reveals both increments of progress (some owing to Sagan’s own efforts) and

continuing menaces.

Most importantly, he highlighted the virtues common to science and civil liberties that are needed to deal with these challenges: freedom of speech, skepticism, constraints on authority, openness to opposing arguments, and an acknowledgment of one’s own fallibility.

The two of us, a cognitive scientist and a civil liberties lawyer, are presenting this lecture to the public at a time when Sagan’s insights are needed even more urgently than they were when originally expressed.

More here.

Three Poems by Tony Hoagland

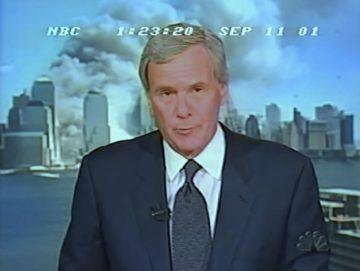

Reality Is Just a Game Now

Jon Askonas in The New Atlantis:

If you ask Americans when was the last time they recall feeling truly united as a country, people over the age of thirty will almost certainly point to the aftermath of 9/11. However briefly, everyone was united in grief and anger, and a palpable sense of social solidarity pervaded our communities.

If you ask Americans when was the last time they recall feeling truly united as a country, people over the age of thirty will almost certainly point to the aftermath of 9/11. However briefly, everyone was united in grief and anger, and a palpable sense of social solidarity pervaded our communities.

Today, just about the only thing everyone agrees on is how divided we are. On issue after issue of vital public importance, people feel that those on the other side are not merely wrong but crazy — crazy to believe what they do about voter ID, Russiagate, critical race theory, pronouns and gender affirmation, take your pick. Americans have always been divided on important issues, but this level of pulling-your-hair-out, how-can-you-possibly-believe-that division feels like something else.

It is hard to imagine how we would have experienced 9/11 in the era of Facebook and Twitter, but the pandemic provides a suggestive example.

More here.

Alasdair MacIntyre – Moral Relativisms Reconsidered