Ian Rose at JSTOR Daily:

One hundred years ago, in 1922, the American musician and scholar W. B. Olds contributed to this debate with “Bird-Music,” an essay whose very title itself demonstrates his position. Olds makes the case that not only is birdsong music, but it’s uniquely beautiful and powerful. To him, each species of bird is a star in its own right, and he gives special mention to a few common American birds; the field sparrow’s song is “a perfect accelerando,” while the song of the white-throated sparrow compels him to ask, “Where is there to be heard a finer legato or more definite rhythm?” Above all, Olds seems most inspired by the tiny ruby-crowned kinglet: “It seems scarcely believable that such a cascade of sparkling tones, extremely high in pitch but wonderfully clear, could proceed from so small a throat. The musician who has not heard it has something to live for.”

more here.

Grief is painful. We all know that. But Is there a “good grief”? Eminent essayist and man of letters

Grief is painful. We all know that. But Is there a “good grief”? Eminent essayist and man of letters  It wasn’t until my mid-forties that I began to write about the world of medicine. Before that, I was busy building a career as a hematologist-oncologist: caring for patients with blood diseases, cancer, and, later, aids; establishing a research laboratory; publishing papers; training junior physicians. A doctor’s workload tends to crowd out everything but the most immediate concerns. But, as the years pass, the things you’ve pushed to the back of your mind start to pile up, demanding to be addressed. For two decades, I had seen my patients and their loved ones face some of life’s most uncertain moments, and I now felt driven to bear witness to their stories.

It wasn’t until my mid-forties that I began to write about the world of medicine. Before that, I was busy building a career as a hematologist-oncologist: caring for patients with blood diseases, cancer, and, later, aids; establishing a research laboratory; publishing papers; training junior physicians. A doctor’s workload tends to crowd out everything but the most immediate concerns. But, as the years pass, the things you’ve pushed to the back of your mind start to pile up, demanding to be addressed. For two decades, I had seen my patients and their loved ones face some of life’s most uncertain moments, and I now felt driven to bear witness to their stories. CHILE’S VILLARRICA NATIONAL PARK—

CHILE’S VILLARRICA NATIONAL PARK— For many generations in societies shaped by Christianity, monogamy has been the almost undisputed champion of relationship norms. In Britain and the US, it has been held up as the dominant – really the only – ideal for serious romantic partnerships, toward which all of us should always be striving. According to the authors of a 2019 article in Archives of Sexual Behavior, focused on the US context, a “halo surrounds monogamous relationships . . . monogamous people are perceived to have various positive qualities based solely on the fact they are monogamous.” Other relationship models, or even just being persistently single, have often been seen as suspect, if not morally wrong.

For many generations in societies shaped by Christianity, monogamy has been the almost undisputed champion of relationship norms. In Britain and the US, it has been held up as the dominant – really the only – ideal for serious romantic partnerships, toward which all of us should always be striving. According to the authors of a 2019 article in Archives of Sexual Behavior, focused on the US context, a “halo surrounds monogamous relationships . . . monogamous people are perceived to have various positive qualities based solely on the fact they are monogamous.” Other relationship models, or even just being persistently single, have often been seen as suspect, if not morally wrong. Germans call it

Germans call it  Published in 1953, The Captive Mind remains possibly the best book ever written about the lure and trap of totalitarian ideology. In his riveting collection of linked essays, the great poet Czesław Miłosz probed the motivations of Polish writers and intellectuals (Miłosz, at one time, included) who joined the Communist regime after World War II. The rewards of the book begin with its epigraph, which Miłosz attributes to “An Old Jew of Galicia”:

Published in 1953, The Captive Mind remains possibly the best book ever written about the lure and trap of totalitarian ideology. In his riveting collection of linked essays, the great poet Czesław Miłosz probed the motivations of Polish writers and intellectuals (Miłosz, at one time, included) who joined the Communist regime after World War II. The rewards of the book begin with its epigraph, which Miłosz attributes to “An Old Jew of Galicia”: I

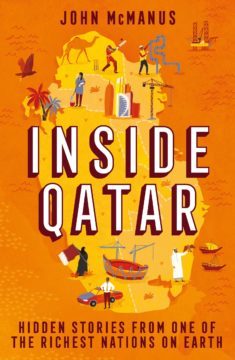

I In Arabia Through the Looking Glass, when he wasn’t comparing everything to Alice in Wonderland, Jonathan Raban likened his experiences in the Gulf States at the height of the 1970s oil boom to passing through a ‘time loop’ into Britain at the heyday of the Industrial Revolution. Today – in polite academic circles, at least – it would constitute a major faux pas to compare the societies of the Middle East with those at some earlier stage of Western historical development. Yet, forty years on, one gains a strikingly similar impression from John McManus’s picture of life in 21st-century Qatar, from the outsized ambition, the extraordinary rate of economic growth and the transformation of the urban environment to the dreadful working conditions, the open racial hierarchies and the persistence of traditional rentier elites. To venture ‘inside Qatar’ in 2022, as McManus puts it, is to get a ‘glimpse of life at the coalface of globalisation’.

In Arabia Through the Looking Glass, when he wasn’t comparing everything to Alice in Wonderland, Jonathan Raban likened his experiences in the Gulf States at the height of the 1970s oil boom to passing through a ‘time loop’ into Britain at the heyday of the Industrial Revolution. Today – in polite academic circles, at least – it would constitute a major faux pas to compare the societies of the Middle East with those at some earlier stage of Western historical development. Yet, forty years on, one gains a strikingly similar impression from John McManus’s picture of life in 21st-century Qatar, from the outsized ambition, the extraordinary rate of economic growth and the transformation of the urban environment to the dreadful working conditions, the open racial hierarchies and the persistence of traditional rentier elites. To venture ‘inside Qatar’ in 2022, as McManus puts it, is to get a ‘glimpse of life at the coalface of globalisation’. Flora Bigelow Dodge had not traveled to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in January 1903 for the same reason so many women of her acquaintance had. She did not do anything for the same reason other women did—at least not if you believed the newspapers. A fixture in the society pages, Flora was the “most daring, most original, cleverest woman in New York.” She was a wonderful musician, a graceful dancer, an expert horsewoman, and a captivating storyteller, an author of plays and short stories. She was “both courageous and imaginative.” She was witty, ambitious, generous, and beautiful, a woman of “unusual individuality” with a retinue of admirers.

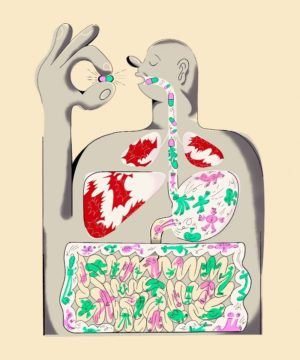

Flora Bigelow Dodge had not traveled to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in January 1903 for the same reason so many women of her acquaintance had. She did not do anything for the same reason other women did—at least not if you believed the newspapers. A fixture in the society pages, Flora was the “most daring, most original, cleverest woman in New York.” She was a wonderful musician, a graceful dancer, an expert horsewoman, and a captivating storyteller, an author of plays and short stories. She was “both courageous and imaginative.” She was witty, ambitious, generous, and beautiful, a woman of “unusual individuality” with a retinue of admirers. Zion Levy remembers the excitement that he and his daughter felt while poring over body scans in 2019, watching small black dots, representing melanoma metastases, shrink away and eventually vanish. They weren’t Levy’s scans. He didn’t even know who the scans came from, but he did share a connection with them.

Zion Levy remembers the excitement that he and his daughter felt while poring over body scans in 2019, watching small black dots, representing melanoma metastases, shrink away and eventually vanish. They weren’t Levy’s scans. He didn’t even know who the scans came from, but he did share a connection with them. Published by Thunder Bay Press, The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics: 1963-1970 offers an attractive, if strangely incomplete, collection of the lyrics that John, Paul, George, and (very rarely) Ringo produced during their 1960s heyday. The brevity of the Beatles’ career—seven short years from “Please Please Me” to “The Long and Winding Road”—remains the most mystifying element of the band, of how so much music poured out of the band in a remarkably brief amount of time. The Beatles Illustrated does not offer any answers or provide any new insight on the Fab Four’s magic—the commentary is limited to Steve Turner’s one-page introduction—but instead captures the bulk of the Beatles’ lyrics alongside some great photos of the band and illustrations that nicely compliment the songs.

Published by Thunder Bay Press, The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics: 1963-1970 offers an attractive, if strangely incomplete, collection of the lyrics that John, Paul, George, and (very rarely) Ringo produced during their 1960s heyday. The brevity of the Beatles’ career—seven short years from “Please Please Me” to “The Long and Winding Road”—remains the most mystifying element of the band, of how so much music poured out of the band in a remarkably brief amount of time. The Beatles Illustrated does not offer any answers or provide any new insight on the Fab Four’s magic—the commentary is limited to Steve Turner’s one-page introduction—but instead captures the bulk of the Beatles’ lyrics alongside some great photos of the band and illustrations that nicely compliment the songs. With its recent

With its recent  Anita’s case was far from unique. According to hospital records, the women’s ward in Herat saw 900 such cases that April. In 2021, the facility recorded 12,678 cases, up from 10,800 cases in 2020.

Anita’s case was far from unique. According to hospital records, the women’s ward in Herat saw 900 such cases that April. In 2021, the facility recorded 12,678 cases, up from 10,800 cases in 2020. Suppose that I am polyamorous and that my mother disapproves. She tolerates my love life but thinks it’s wrong that I have not one partner but two. What her half-accepting, half-critical attitude reveals is a duality at the heart of toleration, an ambivalence that is beautifully captured by the British philosopher

Suppose that I am polyamorous and that my mother disapproves. She tolerates my love life but thinks it’s wrong that I have not one partner but two. What her half-accepting, half-critical attitude reveals is a duality at the heart of toleration, an ambivalence that is beautifully captured by the British philosopher