Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay on the Jain Family Institute’s new project:

What crisis?

A year ago, one might be forgiven for thinking there was a moment of relative calm for wealthy countries: a year of vaccinations had made the pandemic less acute, inflation hadn’t yet provoked interest rate hikes, and labor markets were strong. In the climate world, the energy transition was progressing and, after years of struggle in the UN climate diplomacy track, there was even some sign from rich countries that the poorest and most vulnerable states might be compensated for the loss and damage from climate-fueled disasters.

In reality, all was not well. As anticipated early in the pandemic, dozens of low-income and smaller middle-income countries were continuing to grind towards sovereign debt crises provoked by a sudden drop in foreign income and climbing healthcare costs. Creditors (the wealthy Paris Club countries, multilateral banks, bondholders, and China) had all failed to head off this debt crisis. Meanwhile, vaccines remained unavailable to many people in the poorest countries. Energy costs were climbing.

Then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and historic coordinated economic sanctions by Western governments, made everything much worse—in ways that even the world’s richest countries couldn’t avoid.

Energy costs in Europe were already high going into the winter of 2021. This was driven in part by the curtailment of China’s coal-fired generation leading to more demand for imported gas. In 2022, it’s spilled over into other countries: Europe and richer east Asia countries are now in a bidding war for limited gas supplies. Others have been priced out of the market entirely.

More here.

F

F It’s an anti-Trumper’s nightmare, but it could happen: 47 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents want Trump to be the nominee in 2024, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News

It’s an anti-Trumper’s nightmare, but it could happen: 47 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents want Trump to be the nominee in 2024, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News  O

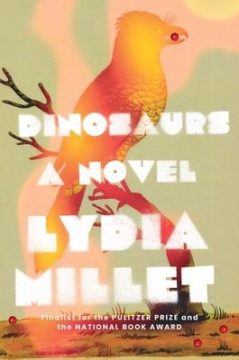

O The novelist Lydia Millet once told an interviewer that when she first moved to New York, in 1996, she was “amazed” by how people were “relentlessly interested in exclusively the human self.” This myopia—a sort of “inarticulate, ambient smugness about everything”—wasn’t her creed. Millet, who now lives near Tucson, has written more than a dozen books of fiction, one of which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, but she works at the Center for Biological Diversity and holds a master’s in environmental policy. As in life, so in art. Increasingly, fiction studies the “arc of the private individual,” Millet told another interviewer: “The personal struggles of a self and the ultimate triumph of that self over the obstacles in its path.” But Millet is energized, instead, by how feelings are “intermeshed with abstract thought,” with “our place in the wider landscape.” Why, her work demands, are we afraid to die? What are the ethics of wanting what we want?

The novelist Lydia Millet once told an interviewer that when she first moved to New York, in 1996, she was “amazed” by how people were “relentlessly interested in exclusively the human self.” This myopia—a sort of “inarticulate, ambient smugness about everything”—wasn’t her creed. Millet, who now lives near Tucson, has written more than a dozen books of fiction, one of which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, but she works at the Center for Biological Diversity and holds a master’s in environmental policy. As in life, so in art. Increasingly, fiction studies the “arc of the private individual,” Millet told another interviewer: “The personal struggles of a self and the ultimate triumph of that self over the obstacles in its path.” But Millet is energized, instead, by how feelings are “intermeshed with abstract thought,” with “our place in the wider landscape.” Why, her work demands, are we afraid to die? What are the ethics of wanting what we want? Down in the crypt of the basilica of Saint-Maximin-La-Sainte-Baume, in the South of France, there is an exquisitely rare object. It is a skull, behind a wall of glass, and it is described by two separate and very different labels. The one label tells you it comes from a woman in her fifties, likely born in the eastern Mediterranean in the early first century CE. The other label tells you it is the skull of Mary Magdalene. Legends of her late-life migration to Southern Gaul had already been circulating for some time when the discovery of her skeletal remains in Saint-Maximin was announced in 1279, and the basilica was subsequently built up around this gravesite. In the fourteenth century the Genoese Dominican author Jacobus de Voragine tells the full story of Mary Magdalene’s shipwreck off the coast of Marseille, and of her subsequent long career of miracle-working throughout Provence. Europe was made Christian not just by real-time conversion, but also a great deal of retroactive inscription of Biblical personages, apostles, and early Church Fathers into the ancient history of what was not yet a well-delineated cultural-geographical sphere.

Down in the crypt of the basilica of Saint-Maximin-La-Sainte-Baume, in the South of France, there is an exquisitely rare object. It is a skull, behind a wall of glass, and it is described by two separate and very different labels. The one label tells you it comes from a woman in her fifties, likely born in the eastern Mediterranean in the early first century CE. The other label tells you it is the skull of Mary Magdalene. Legends of her late-life migration to Southern Gaul had already been circulating for some time when the discovery of her skeletal remains in Saint-Maximin was announced in 1279, and the basilica was subsequently built up around this gravesite. In the fourteenth century the Genoese Dominican author Jacobus de Voragine tells the full story of Mary Magdalene’s shipwreck off the coast of Marseille, and of her subsequent long career of miracle-working throughout Provence. Europe was made Christian not just by real-time conversion, but also a great deal of retroactive inscription of Biblical personages, apostles, and early Church Fathers into the ancient history of what was not yet a well-delineated cultural-geographical sphere. What Carroll wants is to give readers something of the mathematical essence which, after all, is how physics is done. To accomplish this goal he proposes a novel approach. As he rightly notes, to become a practicing physicist, a student must not only learn the equations

What Carroll wants is to give readers something of the mathematical essence which, after all, is how physics is done. To accomplish this goal he proposes a novel approach. As he rightly notes, to become a practicing physicist, a student must not only learn the equations  IT TAKES A STRONG STOMACH for paradox to write that Paul Cézanne “cannot be written about any more.” When art historian T.J. Clark began a 2010 London Review of Books article on the painter this way, he meant no insult. The post-Impressionist and proto-modernist Cézanne was one of the keenest observers of the industrial disenchantment of late 19th-century Western Europe. In the 21st century, Clark argued, his paintings had become “remote to the temper of our times,” ergo, a tough subject. Accordingly, Clark’s new study of the painter, If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present, is a book about Cézanne, but also about the difficulties of writing such a book.

IT TAKES A STRONG STOMACH for paradox to write that Paul Cézanne “cannot be written about any more.” When art historian T.J. Clark began a 2010 London Review of Books article on the painter this way, he meant no insult. The post-Impressionist and proto-modernist Cézanne was one of the keenest observers of the industrial disenchantment of late 19th-century Western Europe. In the 21st century, Clark argued, his paintings had become “remote to the temper of our times,” ergo, a tough subject. Accordingly, Clark’s new study of the painter, If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present, is a book about Cézanne, but also about the difficulties of writing such a book. Giant pandas are found in the wild only in a few mountain ranges in China, primarily in Sichuan province, which means that China controls the supply of one of the world’s most beloved animals. Pandas became a key component of China’s diplomatic relations beginning in the mid-twentieth century, with the first instance of such “panda diplomacy”—as the practice of offering the bears as the highest official gift came to be called—occurring in 1941 when Madame Chiang Kai-shek and her sister gave a pair of pandas to the United States in gratitude for assisting the country in its war with Japan. This began a tradition that continued through the Cold War to the present day, with the animal playing a vital role in China’s relationship with countries including Taiwan, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In 1936, the first living panda arrived in the West. It was brought to the United States illegally by Ruth Elizabeth Harkness, a fashion designer from New York whose husband, William, had died that February in Shanghai while preparing an expedition to capture pandas in Sichuan.

Giant pandas are found in the wild only in a few mountain ranges in China, primarily in Sichuan province, which means that China controls the supply of one of the world’s most beloved animals. Pandas became a key component of China’s diplomatic relations beginning in the mid-twentieth century, with the first instance of such “panda diplomacy”—as the practice of offering the bears as the highest official gift came to be called—occurring in 1941 when Madame Chiang Kai-shek and her sister gave a pair of pandas to the United States in gratitude for assisting the country in its war with Japan. This began a tradition that continued through the Cold War to the present day, with the animal playing a vital role in China’s relationship with countries including Taiwan, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In 1936, the first living panda arrived in the West. It was brought to the United States illegally by Ruth Elizabeth Harkness, a fashion designer from New York whose husband, William, had died that February in Shanghai while preparing an expedition to capture pandas in Sichuan. Historians will look back and see a point of origin to the current madness, one that explains how a new prime minister could see her administration fall apart in a matter of weeks, even if we struggle to name that cause out loud right now. When the textbooks of the future come to the chapter we are living through, in the autumn of 2022, they will start with the summer of 2016:

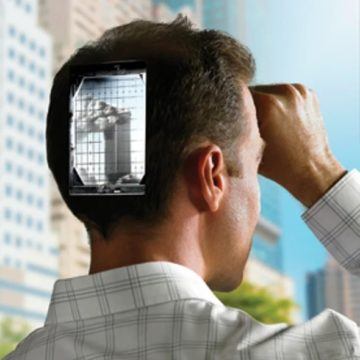

Historians will look back and see a point of origin to the current madness, one that explains how a new prime minister could see her administration fall apart in a matter of weeks, even if we struggle to name that cause out loud right now. When the textbooks of the future come to the chapter we are living through, in the autumn of 2022, they will start with the summer of 2016:  Amid the endless stream of everyday experience, emotion is like a blazing neon tag that alerts the brain, “Yoo-hoo, this is a moment worth remembering!” The salience of the humdrum sandwich you ate for lunch pales in comparison, consigning its memory to the dustbin. Yet emotions regulate our recall of not just our most riveting moments. Researchers now recognize that the same neural mechanisms involved in flashbulb memories underlie recollections along the continuum of human emotional experience. When people view a series of pictures or words in the laboratory, any emotionally laden content sticks in their head better than neutral information.

Amid the endless stream of everyday experience, emotion is like a blazing neon tag that alerts the brain, “Yoo-hoo, this is a moment worth remembering!” The salience of the humdrum sandwich you ate for lunch pales in comparison, consigning its memory to the dustbin. Yet emotions regulate our recall of not just our most riveting moments. Researchers now recognize that the same neural mechanisms involved in flashbulb memories underlie recollections along the continuum of human emotional experience. When people view a series of pictures or words in the laboratory, any emotionally laden content sticks in their head better than neutral information. There are many good reasons to take care of your hearing — from the sound of birds chirping to being able to carry on a conversation in a restaurant. But the best reason to take care of your hearing is to take care of your brain. Hearing loss in middle age — ages 45 to 65 — is the most significant risk factor for dementia, accounting for more than 8 percent of all dementia cases, Richard Sima reports in this week’s

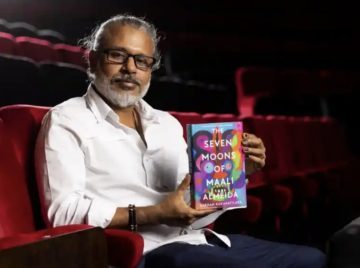

There are many good reasons to take care of your hearing — from the sound of birds chirping to being able to carry on a conversation in a restaurant. But the best reason to take care of your hearing is to take care of your brain. Hearing loss in middle age — ages 45 to 65 — is the most significant risk factor for dementia, accounting for more than 8 percent of all dementia cases, Richard Sima reports in this week’s  The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Sri Lankan author

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Sri Lankan author  Now some computational neuroscientists have begun to explore neural networks that have been trained with little or no human-labeled data. These “self-supervised learning” algorithms have proved enormously successful at

Now some computational neuroscientists have begun to explore neural networks that have been trained with little or no human-labeled data. These “self-supervised learning” algorithms have proved enormously successful at