Bill Gates in his blog, Gates Notes:

When I first started learning about climate change 15 years ago, I came to three conclusions. First, avoiding a climate disaster would be the hardest challenge people had ever faced. Second, the only way to do it was to invest aggressively in clean-energy innovation and deployment. And third, we needed to get going.

When I first started learning about climate change 15 years ago, I came to three conclusions. First, avoiding a climate disaster would be the hardest challenge people had ever faced. Second, the only way to do it was to invest aggressively in clean-energy innovation and deployment. And third, we needed to get going.

Since then, an influx of private and public investment has accelerated innovation faster than I dared hope. This progress makes me optimistic about the future.

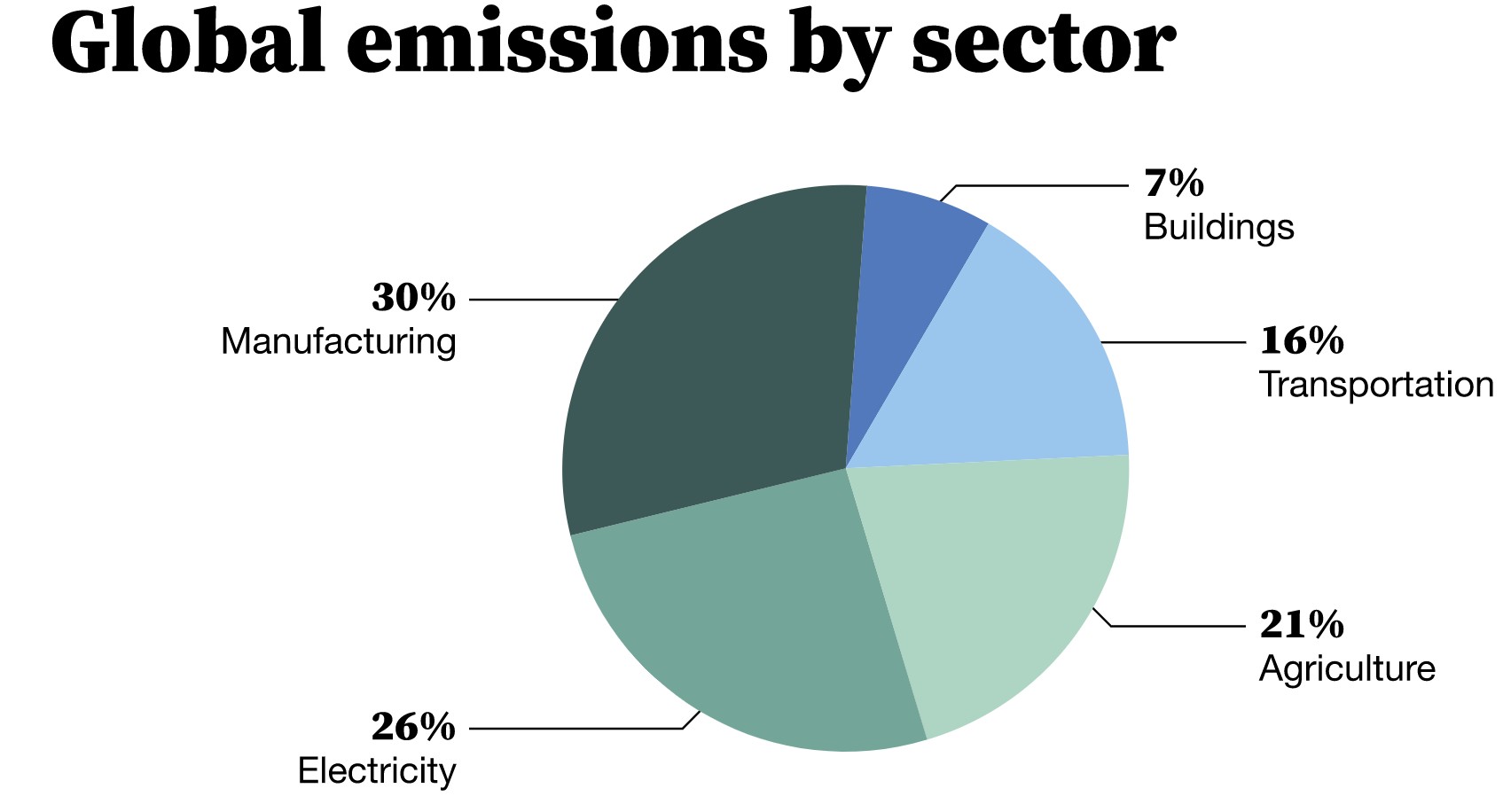

But I am also realistic about the present. The world still needs to reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions from 51 billion tons to zero, but global emissions continue to increase every year. If you follow the annual IPCC reports, you’ve watched as the scenarios for limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 or even 2 degrees Celsius become increasingly remote. And some of the clean technologies we need are still very far from becoming practical, cost-effective solutions we can deploy at scale.

More here.

OVER A DECADE AGO,

OVER A DECADE AGO, I am a recovering perfectionist.

I am a recovering perfectionist. Science is “a shared experience, subject both to the best of what creativity and imagination have to offer and to humankind’s worst excesses”. So wrote the guest editors of this special issue of Nature, Melissa Nobles, Chad Womack, Ambroise Wonkam and Elizabeth Wathuti, in a

Science is “a shared experience, subject both to the best of what creativity and imagination have to offer and to humankind’s worst excesses”. So wrote the guest editors of this special issue of Nature, Melissa Nobles, Chad Womack, Ambroise Wonkam and Elizabeth Wathuti, in a  I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.

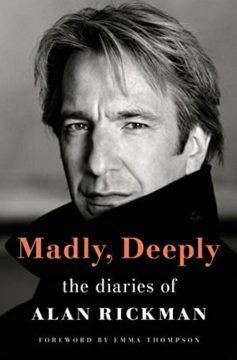

I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread. For anyone with a sneaker for the man and his work, these diaries are a delight. For one thing, they’re filled with his acerbic verdicts on the films and plays he sees. Vicky Cristina Barcelona he dismisses as ‘Woman’s Weekly tosh’, which seems about right. He’s no fan of the over-praised Last Seduction, noting that ‘an espresso is more rewarding’. As for Marvin’s Room, he complains it’s ‘another of those American plays which insist that you feel something’, before adding wryly, ‘I don’t think anger & frustration is what they had in mind.’

For anyone with a sneaker for the man and his work, these diaries are a delight. For one thing, they’re filled with his acerbic verdicts on the films and plays he sees. Vicky Cristina Barcelona he dismisses as ‘Woman’s Weekly tosh’, which seems about right. He’s no fan of the over-praised Last Seduction, noting that ‘an espresso is more rewarding’. As for Marvin’s Room, he complains it’s ‘another of those American plays which insist that you feel something’, before adding wryly, ‘I don’t think anger & frustration is what they had in mind.’ Life Studies is Robert Lowell’s best-known and most influential book. It won the National Book Award for poetry in 1960. I read it in 1962 and I hated it. In a shallow way, my dislike was a matter of social class. I said aloud to Lowell’s book, “Yeah, I had a grandfather, too.” Like my fellow would-be urban Beatniks at Rutgers, I preferred the manners of Allen Ginsberg’s “Kaddish”—the poet reading the Hebrew prayer for the dead while listening to Ray Charles and walking the streets of Greenwich Village.

Life Studies is Robert Lowell’s best-known and most influential book. It won the National Book Award for poetry in 1960. I read it in 1962 and I hated it. In a shallow way, my dislike was a matter of social class. I said aloud to Lowell’s book, “Yeah, I had a grandfather, too.” Like my fellow would-be urban Beatniks at Rutgers, I preferred the manners of Allen Ginsberg’s “Kaddish”—the poet reading the Hebrew prayer for the dead while listening to Ray Charles and walking the streets of Greenwich Village. IN THE SPRING

IN THE SPRING 1) What are the most exciting projects that you’re currently working on? And the most exciting projects that you know of that others are working on?

1) What are the most exciting projects that you’re currently working on? And the most exciting projects that you know of that others are working on?  The U.S. Mint will begin shipping coins featuring actress Anna May Wong on Monday, the first U.S. currency to feature an Asian American. Dubbed Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star, Wong championed the need for more representation and less stereotypical roles for Asian Americans on screen. Wong, who died in 1961, struggled to land roles in Hollywood in the early 20th century, a time of “

The U.S. Mint will begin shipping coins featuring actress Anna May Wong on Monday, the first U.S. currency to feature an Asian American. Dubbed Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star, Wong championed the need for more representation and less stereotypical roles for Asian Americans on screen. Wong, who died in 1961, struggled to land roles in Hollywood in the early 20th century, a time of “

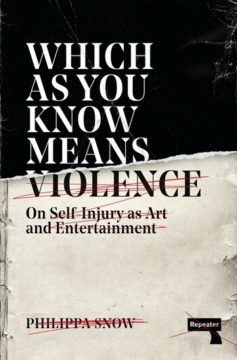

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in monk’s robes and a bloody cilice, or flagellating his back in penance, a commitment to suffering so all-consuming and ridiculous that, by his third murderous jump-scare, it’s a challenge not to laugh mid-flinch.

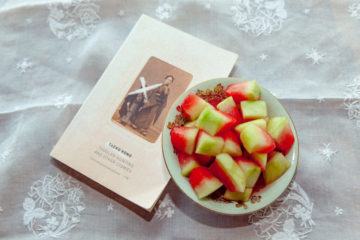

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in monk’s robes and a bloody cilice, or flagellating his back in penance, a commitment to suffering so all-consuming and ridiculous that, by his third murderous jump-scare, it’s a challenge not to laugh mid-flinch. The Japanese writer Taeko Kōno is a maestro of transgressive desire whose stories often—and deliciously—use food as a metaphor for sexual appetite. Kōno, who died in 2015, is considered one of Japan’s foremost feminist writers and one of its foremost writers of any kind. She won many of the country’s top literary prizes, including the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri. The single selection of her work in English, Toddler-Hunting & Other Stories, first published by New Directions in 1996 and translated by Lucy North and Lucy Lower, contains ten dark, deceptively simple stories about women who find the gender roles in Japanese society unbearable, and are warped by them.

The Japanese writer Taeko Kōno is a maestro of transgressive desire whose stories often—and deliciously—use food as a metaphor for sexual appetite. Kōno, who died in 2015, is considered one of Japan’s foremost feminist writers and one of its foremost writers of any kind. She won many of the country’s top literary prizes, including the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri. The single selection of her work in English, Toddler-Hunting & Other Stories, first published by New Directions in 1996 and translated by Lucy North and Lucy Lower, contains ten dark, deceptively simple stories about women who find the gender roles in Japanese society unbearable, and are warped by them.