Zack Savitsky in Science:

When American novelist Kurt Vonnegut addressed the Bennington College class of 1970—1 year after publishing his best-selling novel, Slaughterhouse-Five—he hit the crowd with his signature one-two punch. “I fully expected that by the time I was 21, some scientist … would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine,” he said. “What actually happened … was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima.” This weary skepticism for the scientific endeavor rings through many of Vonnegut’s 14 novels and dozens of short stories. For what would have been the famed author’s 100th birthday, Science talked to literary scholars, philosophers of science, and political theorists about the messages Vonnegut left for the scientific community—and why he’s more relevant than ever.

When American novelist Kurt Vonnegut addressed the Bennington College class of 1970—1 year after publishing his best-selling novel, Slaughterhouse-Five—he hit the crowd with his signature one-two punch. “I fully expected that by the time I was 21, some scientist … would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine,” he said. “What actually happened … was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima.” This weary skepticism for the scientific endeavor rings through many of Vonnegut’s 14 novels and dozens of short stories. For what would have been the famed author’s 100th birthday, Science talked to literary scholars, philosophers of science, and political theorists about the messages Vonnegut left for the scientific community—and why he’s more relevant than ever.

More here.

Francis Fukuyama’s work is generally treated much the way pigeons treat statues: as something on which to deposit badly digested ideas, which are then left for others to clean up. His notoriety for the “End of History” thesis is based on a misreading of that phrase, not a real reading of his 1989 National Interest article “The End of History?” or his less sanguine 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. His subsequent work has received respectful public attention, but little scholarly engagement; he is treated more as a symptom than an intellect. Even with this book, the pattern of neglect-by-vague-praise continues: None of its many reviewers, for all their pretense at comprehension, noticed that his drive-by definition of “deontology” (“not linked to any ontology or substantive theory of human nature”) is totally wrong: Deontology comes from deon, a Greek word here meaning something like “duty” and refers to the study of ethics.

Francis Fukuyama’s work is generally treated much the way pigeons treat statues: as something on which to deposit badly digested ideas, which are then left for others to clean up. His notoriety for the “End of History” thesis is based on a misreading of that phrase, not a real reading of his 1989 National Interest article “The End of History?” or his less sanguine 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. His subsequent work has received respectful public attention, but little scholarly engagement; he is treated more as a symptom than an intellect. Even with this book, the pattern of neglect-by-vague-praise continues: None of its many reviewers, for all their pretense at comprehension, noticed that his drive-by definition of “deontology” (“not linked to any ontology or substantive theory of human nature”) is totally wrong: Deontology comes from deon, a Greek word here meaning something like “duty” and refers to the study of ethics. I teach in and co-direct the undergraduate program in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. During the promotion of my recent book on testosterone and sex differences, I appeared on “Fox and Friends,” a Fox News program, and explained that sex is binary and biological. In response, the director of my department’s Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging task force (a graduate student) accused me on Twitter of transphobia and harming undergraduates, and I responded. The tweets went viral, receiving international news coverage. The public attack by the task force director runs contrary to Harvard’s stated academic freedom principles, yet no disciplinary action was taken, nor did any university administrators publicly support my right to express my views in an environment free of harassment. Unfortunately, what happened to me is not unusual, and an increasing number of scholars face restrictions imposed by formal sanctions or the creation of hostile work environments. In this article, I describe what happened to me, discuss why clear talk about the science of sex and gender is increasingly met with hostility on college campuses, why administrators are largely failing in their responsibilities to protect scholars and their rights to express their views, and what we can do to remedy the situation.

I teach in and co-direct the undergraduate program in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. During the promotion of my recent book on testosterone and sex differences, I appeared on “Fox and Friends,” a Fox News program, and explained that sex is binary and biological. In response, the director of my department’s Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging task force (a graduate student) accused me on Twitter of transphobia and harming undergraduates, and I responded. The tweets went viral, receiving international news coverage. The public attack by the task force director runs contrary to Harvard’s stated academic freedom principles, yet no disciplinary action was taken, nor did any university administrators publicly support my right to express my views in an environment free of harassment. Unfortunately, what happened to me is not unusual, and an increasing number of scholars face restrictions imposed by formal sanctions or the creation of hostile work environments. In this article, I describe what happened to me, discuss why clear talk about the science of sex and gender is increasingly met with hostility on college campuses, why administrators are largely failing in their responsibilities to protect scholars and their rights to express their views, and what we can do to remedy the situation. With the centre-left divided and in perpetual crisis, none of its well-known leaders appears remotely capable of forming an effective opposition movement against the far-right government.

With the centre-left divided and in perpetual crisis, none of its well-known leaders appears remotely capable of forming an effective opposition movement against the far-right government. Low

Low A MONTH BEFORE Atlanta hosted the first hip-hop-focused spinoff of the BET Awards in 2006, an executive at the cable network joked the event would likely not benefit the local economy. He was probably right. Rap dollars already coursed through the Southern city like its ceaseless traffic, bankrolling recording studios, propping up nightclubs and music-publishing companies, and sustaining a vast corps of DJs, strippers, bodyguards, and lawyers. After the inaugural BET Hip Hop Awards aired and nearly half the honors went to Atlantans, local rapper T. I.—who won four awards that night, the largest individual takeaway—described the show’s location as the city’s due: “We control and monopolize so much of this hip-hop industry, it’s only right that they start bringing these awards down here.”

A MONTH BEFORE Atlanta hosted the first hip-hop-focused spinoff of the BET Awards in 2006, an executive at the cable network joked the event would likely not benefit the local economy. He was probably right. Rap dollars already coursed through the Southern city like its ceaseless traffic, bankrolling recording studios, propping up nightclubs and music-publishing companies, and sustaining a vast corps of DJs, strippers, bodyguards, and lawyers. After the inaugural BET Hip Hop Awards aired and nearly half the honors went to Atlantans, local rapper T. I.—who won four awards that night, the largest individual takeaway—described the show’s location as the city’s due: “We control and monopolize so much of this hip-hop industry, it’s only right that they start bringing these awards down here.” Case studies showing bone metastasis

Case studies showing bone metastasis  The day after the midterm election of 2022 that both parties had agreed was the most consequential ever—except for the previous election, and the next one, of course—one thing was clear: the Democrats had defied both history and expectations. There had been no red wave, never mind Donald Trump’s promised “great red wave.” Was it a red ripple or merely a red drizzle? A blue escape? Purple rain? Even Fox News decreed the results to be no more than a pro-Republican “trickle.” Whatever it was called, President Biden and his Democrats, by limiting their losses in the House to less than the average for such elections and likely keeping the Senate as well, scored an against-the-odds political upset that suggests the country remains deeply skeptical of handing too much national power to the Trumpified Republican Party.

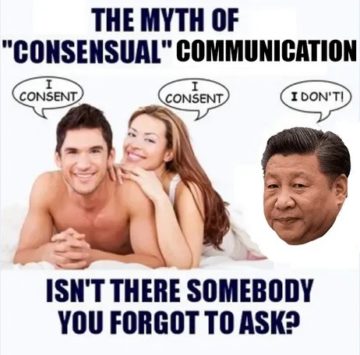

The day after the midterm election of 2022 that both parties had agreed was the most consequential ever—except for the previous election, and the next one, of course—one thing was clear: the Democrats had defied both history and expectations. There had been no red wave, never mind Donald Trump’s promised “great red wave.” Was it a red ripple or merely a red drizzle? A blue escape? Purple rain? Even Fox News decreed the results to be no more than a pro-Republican “trickle.” Whatever it was called, President Biden and his Democrats, by limiting their losses in the House to less than the average for such elections and likely keeping the Senate as well, scored an against-the-odds political upset that suggests the country remains deeply skeptical of handing too much national power to the Trumpified Republican Party. This is a point I keep seeing people miss in the debate about social media.

This is a point I keep seeing people miss in the debate about social media. Knot theory began as an attempt to understand the fundamental makeup of the universe. In 1867, when scientists were eagerly trying to figure out what could possibly account for all the different kinds of matter, the Scottish mathematician and physicist Peter Guthrie Tait showed his friend and compatriot Sir William Thomson his device for generating smoke rings. Thomson — later to become Lord Kelvin (namesake of the temperature scale) — was captivated by the rings’ beguiling shapes, their stability and their interactions. His inspiration led him in a surprising direction: Perhaps, he thought, just as the smoke rings were vortices in the air, atoms were knotted vortex rings in the luminiferous ether, an invisible medium through which, physicists believed, light propagated.

Knot theory began as an attempt to understand the fundamental makeup of the universe. In 1867, when scientists were eagerly trying to figure out what could possibly account for all the different kinds of matter, the Scottish mathematician and physicist Peter Guthrie Tait showed his friend and compatriot Sir William Thomson his device for generating smoke rings. Thomson — later to become Lord Kelvin (namesake of the temperature scale) — was captivated by the rings’ beguiling shapes, their stability and their interactions. His inspiration led him in a surprising direction: Perhaps, he thought, just as the smoke rings were vortices in the air, atoms were knotted vortex rings in the luminiferous ether, an invisible medium through which, physicists believed, light propagated. This book is as much a manifesto as a work of history. The manifesto is timely, important, and utterly persuasive. The history is a bit more complicated, but nevertheless offers an eloquent explanation of much that happened in the long history of Rome and its empire.

This book is as much a manifesto as a work of history. The manifesto is timely, important, and utterly persuasive. The history is a bit more complicated, but nevertheless offers an eloquent explanation of much that happened in the long history of Rome and its empire. The carnivalesque has always been at its core a theological construct, a method of religious critique. Knowing which faiths deserve our opprobrium makes all the difference in how effective such a rebellion shall be. When Medieval society crowned an Abbot of Unreason, that daring act of blasphemy paradoxically depended on an acknowledgment of the sacred; heresy and the divine mutually reinforcing and always dependent on one another. To similarly mock Christianity today is toothless because even with the dangerous rise of fascistic Christian Nationalism, we must take stock of who the real gods of this world are. Adam Kotsko in Neoliberalism’s Demons: On the Political Theology of Late Capital writes that our contemporary normative economic thinking “Aspires to be a complete way of life and a holistic worldview . . . [a] combination of policy agenda and moral ethos.” Just as the Roman Catholic Church was the overreaching and dominant ideology of Western Christendom in the era when the Lord of Misrule poked at the pieties of both pope and prince, now our hegemonic faith is deregulated, privatized, free-market absolutist capitalism. If secularism means anything at all it’s not the demise of religion, but rather the replacement of that previous total system with a new one in the form of neoliberal capitalism.

The carnivalesque has always been at its core a theological construct, a method of religious critique. Knowing which faiths deserve our opprobrium makes all the difference in how effective such a rebellion shall be. When Medieval society crowned an Abbot of Unreason, that daring act of blasphemy paradoxically depended on an acknowledgment of the sacred; heresy and the divine mutually reinforcing and always dependent on one another. To similarly mock Christianity today is toothless because even with the dangerous rise of fascistic Christian Nationalism, we must take stock of who the real gods of this world are. Adam Kotsko in Neoliberalism’s Demons: On the Political Theology of Late Capital writes that our contemporary normative economic thinking “Aspires to be a complete way of life and a holistic worldview . . . [a] combination of policy agenda and moral ethos.” Just as the Roman Catholic Church was the overreaching and dominant ideology of Western Christendom in the era when the Lord of Misrule poked at the pieties of both pope and prince, now our hegemonic faith is deregulated, privatized, free-market absolutist capitalism. If secularism means anything at all it’s not the demise of religion, but rather the replacement of that previous total system with a new one in the form of neoliberal capitalism. It takes a particularly agile intelligence to continue coming to terms with several generations of new art, as regularly, and for as long, as Peter did. Things change and so must arguments, though without losing credibility. One way Peter maintained that trust was by narrating his own inner process, attending to ambivalence and contradiction in print. Changing your mind was not a failure, but a freedom to be carefully guarded. Once, he described this to me as his willingness to entertain the thought that anything, no matter how sacred or unimpeachable, might just be bullshit after all. Then what? Could you trace it backward back into meaning? In conversation Peter often evoked the fourteenth-century spiritual tract The Cloud of Unknowing, which teaches a method of contemplation for willfully releasing all prior conceptions of life on this earth and pushing into this great “unknowing” where God finds you. Acclimate to being uncomfortable and just stay there until the miraculous appears. It lent a theological framework to the techniques he’d developed for encountering art.

It takes a particularly agile intelligence to continue coming to terms with several generations of new art, as regularly, and for as long, as Peter did. Things change and so must arguments, though without losing credibility. One way Peter maintained that trust was by narrating his own inner process, attending to ambivalence and contradiction in print. Changing your mind was not a failure, but a freedom to be carefully guarded. Once, he described this to me as his willingness to entertain the thought that anything, no matter how sacred or unimpeachable, might just be bullshit after all. Then what? Could you trace it backward back into meaning? In conversation Peter often evoked the fourteenth-century spiritual tract The Cloud of Unknowing, which teaches a method of contemplation for willfully releasing all prior conceptions of life on this earth and pushing into this great “unknowing” where God finds you. Acclimate to being uncomfortable and just stay there until the miraculous appears. It lent a theological framework to the techniques he’d developed for encountering art. Last week, in a much heralded-speech at Union Station in Washington, D.C., President Joe Biden

Last week, in a much heralded-speech at Union Station in Washington, D.C., President Joe Biden