Category: Archives

Meet the Mice Who Make the Forest

Brandon Keim in The New York Times:

It’s easy to look at a forest and think it’s inevitable: that the trees came into being through a stately procession of seasons and seeds and soil, and will replenish themselves so long as environmental conditions allow. Hidden from sight are the creatures whose labor makes the forest possible — the multitudes of microorganisms and invertebrates involved in maintaining that soil, and the animals responsible for delivering seeds too heavy to be wind-borne to the places where they will sprout. If one is interested in the future of a forest — which tree species will thrive and which will diminish, or whether those threatened by a fast-changing climate will successfully migrate to newly hospitable lands — one should look to these seed-dispersing animals.

It’s easy to look at a forest and think it’s inevitable: that the trees came into being through a stately procession of seasons and seeds and soil, and will replenish themselves so long as environmental conditions allow. Hidden from sight are the creatures whose labor makes the forest possible — the multitudes of microorganisms and invertebrates involved in maintaining that soil, and the animals responsible for delivering seeds too heavy to be wind-borne to the places where they will sprout. If one is interested in the future of a forest — which tree species will thrive and which will diminish, or whether those threatened by a fast-changing climate will successfully migrate to newly hospitable lands — one should look to these seed-dispersing animals.

“All the oaks that are trying to move up north are trying to track the habitable range,” said Ivy Yen, a biologist at the University of Maine who could be found late one recent afternoon at the Penobscot Experimental Forest in nearby Milford, arranging acorns on a tray for mice and voles to find.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Meal Ticket

We’ve made the turkey’s breast

so large it’s an obstacle to mating,

the birds artificially imbued,

lots of creatures these days

needing an assist with things

they used to do for themselves.

No other earthlings consume as we do,

the planet’s tender rotations

always tempting, commerce

done to a last turn. And the turkeys,

their so-called stupidity

a kind of innocence, stand in

crowded metal pens,

rain falling on those outside,

snoods and wattles trembling,

yellow bills turned up to sky

that once meant promise.

Instinct stirs, hope nesting

in a dark branch of cloud,

just enough to drown them.

by Sally Molini

from Rattle, Winter 2009

Whitson Publishing

Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne

Katherine Rundell in Delancey Place:

Donne was not sent to school. He was missing very little; the schools of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England were grim, ice cold metaphorically and literally. Eton’s dormitory was full of rats; at many of the public schools at the time, the boys burned the furniture to keep warm, threw each other around in their blankets, broke each other’s ribs and occasionally heads. The Merchant Taylors’ school had in its rules the stipulation, ‘unto their urine the scholars shall go to the places appointed them in the lane or street without the court’, which, assuming the interdiction was necessary for a reason, suggests the school would have smelled strongly of youthful pee. Because smoking was believed to keep the plague at bay, at Eton they were flogged for the crime of not smoking. Discipline could be murderous. It became necessary to enforce startling legal limits: ‘when a schoolmaster, in correcting his scholar, happens to occasion his death, if in such correction he is so barbarous as to exceed all bounds of moderation, he is at least guilty of manslaughter; and if he makes use of an instrument improper for correction, as an iron bar or sword … he is guilty of murder.’

Donne was not sent to school. He was missing very little; the schools of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England were grim, ice cold metaphorically and literally. Eton’s dormitory was full of rats; at many of the public schools at the time, the boys burned the furniture to keep warm, threw each other around in their blankets, broke each other’s ribs and occasionally heads. The Merchant Taylors’ school had in its rules the stipulation, ‘unto their urine the scholars shall go to the places appointed them in the lane or street without the court’, which, assuming the interdiction was necessary for a reason, suggests the school would have smelled strongly of youthful pee. Because smoking was believed to keep the plague at bay, at Eton they were flogged for the crime of not smoking. Discipline could be murderous. It became necessary to enforce startling legal limits: ‘when a schoolmaster, in correcting his scholar, happens to occasion his death, if in such correction he is so barbarous as to exceed all bounds of moderation, he is at least guilty of manslaughter; and if he makes use of an instrument improper for correction, as an iron bar or sword … he is guilty of murder.’

Instead, Donne was educated at home.

More here.

Sunday, November 27, 2022

Gone Bad, Come to Life: On Fermentation, Distillation, and Sobriety

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack newsletter, The Hinternet:

Is any product of bourgeois consumer ideology more noxious than the “bucket list”? At just the moment a person should be adjusting their orientation, in conformity with their true nature, to focus exclusively on the horizon of mortality, they are rudely solicited one last time, before it’s really too late, for a final blow-out tour of the amusement parks and spectacles that still held out some plausible hope of providing satisfaction back in ignorant youth, when life could still be imagined to be made up of such things. “Travel is a meat thing”, William Gibson wrote, to which we might add that the quest for new experiences in general is really only fitting for those whose meat is still fresh.

Is any product of bourgeois consumer ideology more noxious than the “bucket list”? At just the moment a person should be adjusting their orientation, in conformity with their true nature, to focus exclusively on the horizon of mortality, they are rudely solicited one last time, before it’s really too late, for a final blow-out tour of the amusement parks and spectacles that still held out some plausible hope of providing satisfaction back in ignorant youth, when life could still be imagined to be made up of such things. “Travel is a meat thing”, William Gibson wrote, to which we might add that the quest for new experiences in general is really only fitting for those whose meat is still fresh.

But our economic order cannot accept this. Capitalism obscures from view first the meaning of life, which properly understood is a preparation for death, and then it obscures the meaning of death, which properly understood is the all-surrounding horizon of a mortal life.

More here.

Promising universal flu vaccine could protect against all 20 known strains

Carissa Wong in New Scientist:

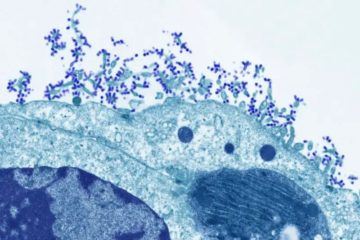

An experimental vaccine has generated antibody responses against all 20 known strains of influenza A and B in animal tests, raising hopes for developing a universal flu vaccine.

An experimental vaccine has generated antibody responses against all 20 known strains of influenza A and B in animal tests, raising hopes for developing a universal flu vaccine.

Influenza viruses are constantly evolving, making them a moving target for vaccine developers. The annual flu vaccines available now are tailored to give immunity against specific strains predicted to circulate each year. However, researchers sometimes get the prediction wrong, meaning the vaccine is less effective than it could be in those years.

Some researchers think annual flu jabs could be replaced by a universal flu vaccine that is effective against all flu strains. Researchers have tried to achieve this by making vaccines containing protein fragments that are common to several influenza strains, but no universal vaccine has yet gained approval for wider use.

Now, Scott Hensley at the University of Pennsylvania and his colleagues have created a vaccine based on mRNA molecules – the same approach that was pioneered by the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna covid-19 vaccines.

More here.

Making Sense of Moral Change

Christopher Leslie Brown interviewed at Asterisk Magazine:

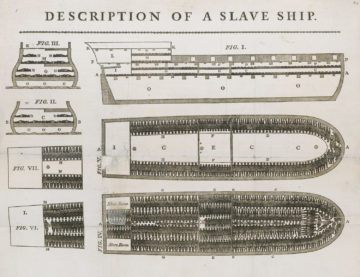

Asterisk: Your book Moral Capital is about why the movement to abolish the slave trade in Britain happened in the late 1780s and not earlier. Would you mind briefly walking through the thrust of that argument?

Asterisk: Your book Moral Capital is about why the movement to abolish the slave trade in Britain happened in the late 1780s and not earlier. Would you mind briefly walking through the thrust of that argument?

Christopher: While it’s not easy to boil down the entire book, essentially, there’s a group of people who gather in the late 1780s and commit themselves to convincing British authorities to abolish Britain’s slave trade. The book explains how that group came together, who they were and why they chose that particular issue. The broad answer is that the circumstances of the American Revolution and its aftermath created an environment with new political, moral and cultural values that did not exist before. I don’t argue that the American Revolution caused the antislavery movement, but that it created the conditions that made the movement possible.

More here.

Interview with David Hume

Richard Marshall at 3:16 AM:

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

David Hume: When I turned my eye inward, I found nothing but doubt and ignorance. Truth is, Richard, all the world conspires to oppose and contradict me; tho’ such is my weakness that I feel all my opinions loosen and fall of themselves, when unsupported by the approbation of others. Can I be sure, that, in leaving all established opinions, I am following truth? and by what criterion shall I distinguish her, even if fortune should at last guide me on her footsteps? After the most accurate and exact of my reasonings, I can give no reason why I should assent to it; and feel nothing but a strong propensity to consider objects strongly in that view under which they appear to me. The memory, senses, and understanding, are all of them founded on the imagination. No wonder a principle so inconstant and fallacious should lead us into errors, when implicitly followed (as it must be) in all its variations. The understanding, when it acts alone, and according to its most general principles, entirely subverts itself, and leaves not the lowest degree of evidence in any proposition either in philosophy or common life. We have no choice left, but betwixt a false reason and none at all. Should I endeavor to banish these sentiments, I feel I should be a loser in point of pleasure; and this is the origin of my philosophy.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Return to Sibiu

After a year of absence

I find my house strewn with feathers.

From the paintings, what first disappeared

was the sea.

Only a fish’s gasping mouth remained alive,

bubbling words.

Moon rays curled obediently

in my coffee cup

and an invisible bird measured invisible time

inside a clock where she’d built her nest.

“Georg,” she whispered.

“Philipp,” the echo sang back.

“Telemann,” I say aloud

while the record is spinning

and the violin strings

accompany your body

a world away.

Like an unseen orchestra:

Presto, say your fingers

Corsicana, answer my fingers

Allegrezza, say your eyes

Scherzo, answer my eyes

Gigue, say your patent-leather shoes

Polacca, answers my white dress

Menuet, answer our bodies, dancing in a ring

on the perfect Street of the Bards . . .

by Lilliana Ursu

from Blackbird

Proust’s death, 100 years ago, was an ending but not the end

Charles Arrowsmith in The Washington Post:

Does solitude equate to loneliness?

Peter Attia in peterattiamd.com:

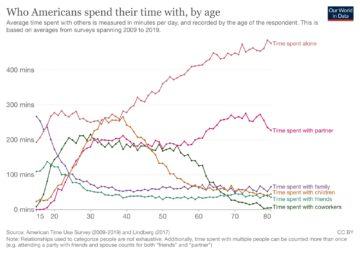

I recently shared a graph on Instagram representing whom we spend time with across our lifetime, collected from 2009 to 2019 as part of the American Time Use Survey (Figure 1). For the most part, the numbers make intuitive sense. The amount of time we spend with our coworkers starts dropping in our mid-fifties as we begin to retire, and time with partners rises concurrently. Time spent with children spikes during the typical child-bearing years of our twenties and thirties and falls again as we reach the “empty nest” stage.

I recently shared a graph on Instagram representing whom we spend time with across our lifetime, collected from 2009 to 2019 as part of the American Time Use Survey (Figure 1). For the most part, the numbers make intuitive sense. The amount of time we spend with our coworkers starts dropping in our mid-fifties as we begin to retire, and time with partners rises concurrently. Time spent with children spikes during the typical child-bearing years of our twenties and thirties and falls again as we reach the “empty nest” stage.

Figure 1: Who Americans spend their time with, by age.

These data demonstrate that most of us enjoy a diversity of social connections daily, and yet, throughout virtually all of our lifespan, we spend more time alone than with any given relationship. Especially eye-catching is the rapid increase in time spent alone after the age of forty, and beyond our early sixties, we spend, on average, more than seven waking hours alone.

Guaranteed loneliness?

The same article, published by Our World in Data, interestingly shows that the percentage of Americans living alone across all age groups has been increasing throughout history, as shown in Figure 2 (one exception being a recent decline in the age 75 group, though this is likely an artifact of increased life expectancy). In just the past half-century, the proportion of people living alone has almost doubled. In fact, more than 40% of people over the age of 89 live alone. So not only do we spend more time alone as we age, we also spend more time alone than our historical counterparts at all ages. These combined trends raise the question: are we growing lonely?

Despite these statistics, time spent alone does not reflect a loss of meaningful social connection and does not predict loneliness.

More here.

Saturday, November 26, 2022

Bad Trade

Michael Pettis in American Compass:

Michael Pettis in American Compass:

“China will compete for some low-wage jobs with Americans,” lectured Nobel laureate Robert Solow from the White House podium, amidst the U.S. debate over China’s ascension to the World Trade Organization. “And their market will provide jobs for higher wage, more skilled people. And that’s a bargain for us.” More than 20 years later, economists and policymakers are still searching for that bargain. Belatedly, they are discovering that whether or not trade benefits the global economy or any particular nation depends, like most things in economics, on the specific underlying economic conditions.

When it comes to trade, the key conditions are the approaches that countries take in their quests for international competitiveness. Trade can directly boost production and indirectly boost demand, so that the global economy is generally better off. But trade can also make the global economy worse off by directly constraining demand and so indirectly constraining production. The outcome depends on whether a country’s higher export revenues are recycled into higher consumption and imports or into higher savings.

In the traditional view, international trade allows a country or region to specialize in producing things that it can produce relatively more efficiently than its trading partners, and so trade shifts production to the locale in which a given amount of labor and capital yields the greatest output. In a world of scarce inputs, this allows the global economy to maximize production. According to that model, by definition, anything that impedes or distorts free trade, whether a regulation or tariff or quota, reduces global production. Mainstream economists accept that the benefits of free trade may be badly distributed, even to the point at which free trade can leave some sectors worse off, but this, they insist, is a distribution problem that should be solved politically.

More here.

Rearguard Battle

Martijn Konings in Sidecar:

Martijn Konings in Sidecar:

The award of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences to Ben Bernanke last month unleashed a wave of indignation among those who view the former chair of the Federal Reserve as the epitome of unoriginal establishment thinking. Bernanke received the prize for work demonstrating that bank runs were possible and that they could impact real economic activity. Both of those things had been perfectly obvious since at least the 1930s. But the Keynesian models that the economics profession built during the post-war era were unable to account for such events, having no real explanation for the volatile dynamics of debt and finance.

This aporia became more obvious when the era of ‘fiscal dominance’ came to an end and financial instability made a comeback from the second half of the 1960s, challenging the Keynesian paradigm and lending credibility to rival strands of thought. Rational expectations theorists underscored the inherent futility of government attempts to interfere with the inner workings of the market, while Milton Friedman’s monetarism fostered the notion that Keynesian inflationism was responsible for the corruption of America’s monetary standard.

Bernanke and other New Keynesians didn’t buy the idea that the problems of the present could be solved by returning to a pure free market. Yet the shallowness of their take on the problem of capitalism’s instability was evident in the subsequent evolution of Bernanke’s work into a framework for inflation targeting and monetary fine-tuning that looked with suspicion on any attempts to manage stock markets or asset prices.

More here.

The Wall Street Consensus at COP27

Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World:

Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World:

At COP26, US Special Envoy for Climate John Kerry sanguinely declared the need to “derisk the investment, and create the capacity to have bankable deals. That’s doable for water, it’s doable for electricity, it’s doable for transportation.” Derisking is financial speak for the public sector—be it through official development aid, multilateral resources or national fiscal resources—accepting to take some risks from private financiers in order to persuade them to invest, public efforts variously described as “mobilizing private finance”or “blended finance.” In response, the UN Special Envoy for Climate and head of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) Mark Carney announced GFANZ’s intentions to work in partnership with governments and multilateral development institutions to mobilize its $130 trillion for green purposes.

At this year’s COP27 in Egypt, Carney was less triumphant. On the contrary, he defensively explained why the GFANZ financiers had dropped the partnership with UN Race to Zero, intended to police their green pledges and reduce pervasive greenwashing. No longer flanked by top financiers like BlackRock’s Larry Fink (who reportedly stayed away to avoid further incensing the US Republican party), and amid several reports denouncing the systematic failure of the GFANZ-Global North mobilization drive, Carney cut a lonely figure.

More here.

Between Tragedy and Techno-Optimism: The New Climate Realpolitik

Mona Ali in Green:

Mona Ali in Green:

The Prado and the Reina Sofia museums were closed to the public for the two-day NATO summit held in Madrid in the last week of June. A day before the summit, at the Sophia, in front of Picasso’s Guernica, Extinction Rebellion, and Fridays for Future staged a die-in. Five thousand NATO delegates had descended upon Madrid. They were doubled by a security entourage numbering ten thousand. That same week the US Supreme Court had rescinded the reproductive rights of women, clamped down on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to curb greenhouse gas emissions, and eased the right to carry concealed weapons in the United States. Yet the chaos that America’s legal machine had unleashed, was temporarily set aside by Biden’s team at the Madrid summit, replaced by revivified notions of hegemonic stability.

In NATO’s hierarchy, the US occupies the role of supreme commander. NATO’s Strategic Concept, its vision statement, explicitly affirms America’s nuclear capability as the crux of North Atlantic security 1 . Following Russia’s war on Ukraine, NATO’s newly updated policy manifesto strikes out its planned strategic partnership with Russia in 2010 to an aggressive stance against the Eurasian power. A more constant feature of the Strategic Concept over the decades is the reminder that if one NATO member is attacked, Article 5 may be invoked, allowing the alliance to engage in retaliatory attack. Ukraine’s EU membership may take years but over a hundred thousand US troops are now stationed in Europe. Since January, this number has increased by twenty thousand.

America’s largest military expansion in Europe since the Cold War—is accompanied by its refueling of Europe. US liquified natural gas now accounts for almost half of European LNG imports, a stunning reversal from just last year when US LNG was shunned by Europe out of ESG concerns.

More here.

The accidental book review that made Jack Kerouac famous

Ronald Collins in The Washington Post:

In early September 1957, Jack Kerouac achieved the dream of every writer. Around midnight he and his girlfriend, Joyce Glassman, left her brownstone apartment in New York City for a nearby newsstand at Broadway and 66th Street. They waited while the nightman cut the twine around the morning edition of the New York Times. Rifling through the paper, they found on Page 27 an expected review of Kerouac’s new book, “On the Road.”

In early September 1957, Jack Kerouac achieved the dream of every writer. Around midnight he and his girlfriend, Joyce Glassman, left her brownstone apartment in New York City for a nearby newsstand at Broadway and 66th Street. They waited while the nightman cut the twine around the morning edition of the New York Times. Rifling through the paper, they found on Page 27 an expected review of Kerouac’s new book, “On the Road.”

Glassman recalled that she “felt dizzy reading the first paragraph.”

Kerouac was reading along, too. “It’s good, isn’t it?” he asked.

“Yes, it’s very, very good,” Glassman recounted in her 1983 memoir.

That breakthrough review, written by Gilbert Millstein in the “Books of the Times” column, changed the course of literary history and the career of Kerouac, who died 50 years ago this fall, on Oct. 21, 1969. If not for that review, Kerouac might have remained a minor writer and the Beat Generation so fully associated with his name may never have flourished as it did. After all, seven years earlier, Kerouac had published his first book, “The Town and the City,” to modest reviews, which were not enough to propel him to fame.

With the first line of his critique of “On the Road,” Millstein announced a work of transcendent proportions. “Its publication is a historic occasion,” he proclaimed. In the piece, he probed the depths of Kerouac the writer and explored the breadth of “On the Road.” Millstein billed the pseudo-philosophic road novel as an “authentic work of art.” After examining the sociological and psychological dimensions of the book, he rhapsodized over its style, declaring, “The writing is of a beauty almost breathtaking.” And he quoted what would become the canonical lines from the novel: “The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles.”

More here.

Elite Capture: How can studying, thinking, reading and writing change the world?

Nicholas Whittaker in The Point:

In their controversial 2013 opus The Undercommons, radicals Fred Moten and Stefano Harney detail the eponymous academic-activist ferment to which they owe their radicality. The undercommons is located in the university—more generally, in the swarm of relations and systems we could call “academia” or “intellectual life”—but is not a physical place; rather, it is a “downlow lowdown maroon community of the university … where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still black, still strong.”

In their controversial 2013 opus The Undercommons, radicals Fred Moten and Stefano Harney detail the eponymous academic-activist ferment to which they owe their radicality. The undercommons is located in the university—more generally, in the swarm of relations and systems we could call “academia” or “intellectual life”—but is not a physical place; rather, it is a “downlow lowdown maroon community of the university … where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still black, still strong.”

The undercommons is defined both by a particular kind of community and a particular kind of work. Who makes up this community? Those who “steal” from the university: those who do their work while eliding—working alongside, underneath, without much concern or attention to, or with an eye toward gaming—the structures of professionalization, profit-chasing, respectability politics, solipsistic individualism and statism that many see as entrenched within modern academia. The undercommons, in other words, is the set of social relationships that interlinks academics and intellectuals who steal paychecks, lecturing positions, office space and so on in order to do work the university would rather they not do.

What, then, is this work? It is the work Adrian Piper accomplishes when, fed up with the obsessive professionalism and bad faith of the system of academic publishing, she releases her magnum opus for free online, where it circulates to this day. It is the work Edward Said accomplishes when he is photographed throwing a stone across the Israel-Lebanon Blue Line, two years after his documentary detailing the atrocities of Israel’s colonial occupation of Palestine is blacklisted from American broadcasting.

More here.

Saturday Poem

On the Shelf

On the kitchen shelf a huntsman spider has left

its skin, which looks so much like itself

I thought twice before touching it. It was still.

The body left and left behind the soul,

feather-light and eight-legged, able to frighten

even when all it wanted was new life.

Perhaps you’ll come upon my own shed skins

in houses where my name has been removed,

the habitations I once thought were home,

or find some words of mine in an old book.

I meant them. The words. Every one of them,

but left them on the shelf to go on living.

by David Mason

from Pacific Light

Red Hen Press, Pasadena, CA, 2022

Friday, November 25, 2022

“On Freedom”: A Reading and Conversation with Maggie Nelson

Young Eliot: From St. Louis to The Waste Land

Michael Thurston at The Hudson Review:

Of most interest to us, the readers of Eliot’s poetry, is the writing of verse for which he somehow found the time and energy. The early drama in Crawford’s account is Eliot’s composition of “The Hollow Men” and “Ash Wednesday” out of his struggles with the frailty of the body (exemplified in Vivien’s constant and severe intestinal illness and his own frequent bouts of flu and bronchitis) and the soul (tormented by shame over the body’s needs and failures, including the repeated fall into sexual guilt). Tormented, Eliot turned to an array of cultural resources. While Baudelaire and Dante continued to inform his thinking, they were joined now by an increasing interest in the theatre, especially the non-naturalistic modes available in puppetry, ballet, and mechanistic work. The poetry of other languages and the suspension of access to meaning entailed in the act of translation helped him to incorporate estrangement into his own poems; Eliot’s labor on a translation of Saint-John Perse’s Anabasis shaped the lines and phrases of his work of the mid-1920s. But the cultural resources Eliot brought to the processing of pain were not limited to the literary.

Of most interest to us, the readers of Eliot’s poetry, is the writing of verse for which he somehow found the time and energy. The early drama in Crawford’s account is Eliot’s composition of “The Hollow Men” and “Ash Wednesday” out of his struggles with the frailty of the body (exemplified in Vivien’s constant and severe intestinal illness and his own frequent bouts of flu and bronchitis) and the soul (tormented by shame over the body’s needs and failures, including the repeated fall into sexual guilt). Tormented, Eliot turned to an array of cultural resources. While Baudelaire and Dante continued to inform his thinking, they were joined now by an increasing interest in the theatre, especially the non-naturalistic modes available in puppetry, ballet, and mechanistic work. The poetry of other languages and the suspension of access to meaning entailed in the act of translation helped him to incorporate estrangement into his own poems; Eliot’s labor on a translation of Saint-John Perse’s Anabasis shaped the lines and phrases of his work of the mid-1920s. But the cultural resources Eliot brought to the processing of pain were not limited to the literary.

more here.

One hundred years ago, on Nov. 18, 1922, Marcel Proust breathed his last in Paris at age 51. His death, from pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess, was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the belle epoque, an age of gentility, civility and artistic achievement that had mostly ended with the outbreak of World War I. At the time, several volumes of Proust’s gargantuan, seven-part novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu” (“

One hundred years ago, on Nov. 18, 1922, Marcel Proust breathed his last in Paris at age 51. His death, from pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess, was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the belle epoque, an age of gentility, civility and artistic achievement that had mostly ended with the outbreak of World War I. At the time, several volumes of Proust’s gargantuan, seven-part novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu” (“