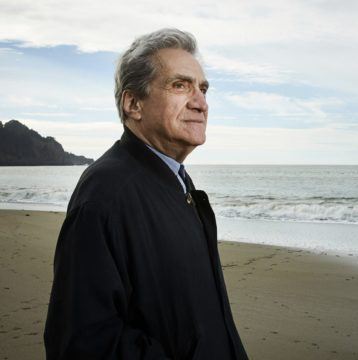

Brian Stewart in Quillette:

Barely four decades into its existence, the Islamic republic is confronted by another eruption of public rage, this time brought about by the nation’s women, that may yet end in revolutionary change. A majority of Iranians now groaning under this austere order have no recollection of the revolution that produced it, and reject its central justification—an Islamic concept known as velayat-e faqih, or “guardianship of the jurist.” Originally conceived as a license for the clergy to assume responsibility for orphans and the infirm, the late Ayatollah Khomeini amended it to encompass the whole of society. By these means were his unfortunate subjects relegated to the status of state property.

Barely four decades into its existence, the Islamic republic is confronted by another eruption of public rage, this time brought about by the nation’s women, that may yet end in revolutionary change. A majority of Iranians now groaning under this austere order have no recollection of the revolution that produced it, and reject its central justification—an Islamic concept known as velayat-e faqih, or “guardianship of the jurist.” Originally conceived as a license for the clergy to assume responsibility for orphans and the infirm, the late Ayatollah Khomeini amended it to encompass the whole of society. By these means were his unfortunate subjects relegated to the status of state property.

More here.

Today more than 2.3 million people live in Doha, while Qatar as a whole has a population of 2.9 million, just 300,000 of whom are Qatari citizens. The rest are migrant workers, only a small proportion of whom – Arabic Levantine and Indian families that arrived a generation or two back – have residence rights. Everyone else is there on a temporary work visa: professionals from the Global North; Filipinos, who make up a large proportion of Qatar’s domestic workers and cleaners; Africans, many of whom work as taxi drivers or security guards; and almost a million men from South Asia, Nepal and Bhutan who have toiled to build the new city. This racialised hierarchy, as John McManus argues in his anthropological account of Qatar, is a modern version of the British Empire’s ethnic division of labour.

Today more than 2.3 million people live in Doha, while Qatar as a whole has a population of 2.9 million, just 300,000 of whom are Qatari citizens. The rest are migrant workers, only a small proportion of whom – Arabic Levantine and Indian families that arrived a generation or two back – have residence rights. Everyone else is there on a temporary work visa: professionals from the Global North; Filipinos, who make up a large proportion of Qatar’s domestic workers and cleaners; Africans, many of whom work as taxi drivers or security guards; and almost a million men from South Asia, Nepal and Bhutan who have toiled to build the new city. This racialised hierarchy, as John McManus argues in his anthropological account of Qatar, is a modern version of the British Empire’s ethnic division of labour. In the three-minute short MANGOES (1999) by Berlin-based Pakistani artist Bani Abidi, two women sit next to each other on a white table, each with a mango on a plate in front of them. Both women are played by Abidi. One character has her hair up in a bun, the other loose and flowing down her shoulders. One is Indian, the other Pakistani, both members of the diaspora of an unspecified country. They slice and pull open their respective mangoes, sucking the flesh clean off the skin. The fruit is an oblique symbol of their melancholy and wistful nationalism. As they eat, they speak about the mango-eating traditions of both nation states, but the conversation soon grows strained as they compete over which has more varieties of mango. It’s an arbitrary, quasi-comic tension, but perfectly representative of the sentiments of animosity and hostility that have ruled Indian and Pakistani relations for over seven decades since the Partition of the subcontinent in 1947. Much of Indian/Pakistani difference is mediated and maintained by trivial, and often untrue, distinctions. But it is the myth of this difference that reinforces the border and fuels its continuing clashes. Abidi uses the mango to disturb the border relation: while the Indo-Pak border is a physical site of military presence, surveillance and catastrophe, it is also something a bit more intangible, something conjured and retained in the imagination of those that inhabit it.

In the three-minute short MANGOES (1999) by Berlin-based Pakistani artist Bani Abidi, two women sit next to each other on a white table, each with a mango on a plate in front of them. Both women are played by Abidi. One character has her hair up in a bun, the other loose and flowing down her shoulders. One is Indian, the other Pakistani, both members of the diaspora of an unspecified country. They slice and pull open their respective mangoes, sucking the flesh clean off the skin. The fruit is an oblique symbol of their melancholy and wistful nationalism. As they eat, they speak about the mango-eating traditions of both nation states, but the conversation soon grows strained as they compete over which has more varieties of mango. It’s an arbitrary, quasi-comic tension, but perfectly representative of the sentiments of animosity and hostility that have ruled Indian and Pakistani relations for over seven decades since the Partition of the subcontinent in 1947. Much of Indian/Pakistani difference is mediated and maintained by trivial, and often untrue, distinctions. But it is the myth of this difference that reinforces the border and fuels its continuing clashes. Abidi uses the mango to disturb the border relation: while the Indo-Pak border is a physical site of military presence, surveillance and catastrophe, it is also something a bit more intangible, something conjured and retained in the imagination of those that inhabit it. The Blindest Man follows the story of the elusive Chouette d’Or (or ‘golden owl’)—a golden sculpture buried somewhere in France in 1993 by an author working under the pseudonym of Max Valentin. The same year, Valentin—whose real name was later revealed to be Régis Hauser—released an accompanying book entitled On The Trail of the Golden Owl, which included 11 cryptic clues as to the statuette’s exact location. It became something of a phenomenon in France back then, and almost 30 years later, many people continue to search for it. To this day, however, it remains unfound, and the author has long since passed. Made in France between 2015 and 2018, the pictures in The Blindest Man introduce us to a number of different people on the hunt for the golden owl, following along on their failed routes. These people are referred to as ‘the searchers’.

The Blindest Man follows the story of the elusive Chouette d’Or (or ‘golden owl’)—a golden sculpture buried somewhere in France in 1993 by an author working under the pseudonym of Max Valentin. The same year, Valentin—whose real name was later revealed to be Régis Hauser—released an accompanying book entitled On The Trail of the Golden Owl, which included 11 cryptic clues as to the statuette’s exact location. It became something of a phenomenon in France back then, and almost 30 years later, many people continue to search for it. To this day, however, it remains unfound, and the author has long since passed. Made in France between 2015 and 2018, the pictures in The Blindest Man introduce us to a number of different people on the hunt for the golden owl, following along on their failed routes. These people are referred to as ‘the searchers’. THERE IS NO other novel quite like Michael Fessier’s 1935 genre-bending Fully Dressed and in His Right Mind. At first glance, the San Francisco–set tale is classic noir, narrated in the steely patter of Depression-era hard-boiled crime fiction. An average Joe, John Price, happens upon a murder in the street; he then becomes unwillingly entangled in the perpetrator’s subsequent killings; and finally, he must prove his innocence when the police try to railroad Price for the other’s crimes. But what elevates Fully Dressed into a class all its own is how Fessier incorporates fantastical characters and events that are alien to noir. The incongruity between the novel’s deadpan, tough-guy prose and its wildly surreal content makes Fully Dressed and in His Right Mind a haunting novel that’s impossible to put down.

THERE IS NO other novel quite like Michael Fessier’s 1935 genre-bending Fully Dressed and in His Right Mind. At first glance, the San Francisco–set tale is classic noir, narrated in the steely patter of Depression-era hard-boiled crime fiction. An average Joe, John Price, happens upon a murder in the street; he then becomes unwillingly entangled in the perpetrator’s subsequent killings; and finally, he must prove his innocence when the police try to railroad Price for the other’s crimes. But what elevates Fully Dressed into a class all its own is how Fessier incorporates fantastical characters and events that are alien to noir. The incongruity between the novel’s deadpan, tough-guy prose and its wildly surreal content makes Fully Dressed and in His Right Mind a haunting novel that’s impossible to put down. What books would you recommend to somebody who wants to understand present-day Japan?

What books would you recommend to somebody who wants to understand present-day Japan? Just how anti-American is Pakistan?

Just how anti-American is Pakistan? In “

In “ Tycoons are susceptible to the misconception that if you know how to make billions you know how to spend them. Sam Bankman-Fried, the “

Tycoons are susceptible to the misconception that if you know how to make billions you know how to spend them. Sam Bankman-Fried, the “ A ROMANIAN FILMMAKER who regularly deflates Romanian myths of national greatness, Radu Jude recently graced the New York Film Festival with a compact, farcical essay on the material basis of historical memory, or, to use Trotsky’s term, “the dustbin of history.”

A ROMANIAN FILMMAKER who regularly deflates Romanian myths of national greatness, Radu Jude recently graced the New York Film Festival with a compact, farcical essay on the material basis of historical memory, or, to use Trotsky’s term, “the dustbin of history.” The creation of Steven Knight of Peaky Blinders fame, it shares with that series a fondness for mythologising and aphoristic dialogue. Set in the Egyptian desert in 1941 as the British army struggles to defend besieged Tobruk from the Germans, its tone is midway between the war comics my brother used to read as a boy (he favoured Battle) and a Duran Duran video – and I mean this as a compliment.

The creation of Steven Knight of Peaky Blinders fame, it shares with that series a fondness for mythologising and aphoristic dialogue. Set in the Egyptian desert in 1941 as the British army struggles to defend besieged Tobruk from the Germans, its tone is midway between the war comics my brother used to read as a boy (he favoured Battle) and a Duran Duran video – and I mean this as a compliment. It is hard to imagine anyone who has done more to champion poetry than Robert Pinsky. The author of 10 collections of poems—including the Pulitzer Prize–nominated The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems, 1966-1996—Pinsky has edited anthologies, written more than a half-dozen prose books about poetry, and translated Dante’s Inferno and the poems of Czesław Miłosz. As director of

It is hard to imagine anyone who has done more to champion poetry than Robert Pinsky. The author of 10 collections of poems—including the Pulitzer Prize–nominated The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems, 1966-1996—Pinsky has edited anthologies, written more than a half-dozen prose books about poetry, and translated Dante’s Inferno and the poems of Czesław Miłosz. As director of