Category: Archives

New Human Metabolism Research Upends Conventional Wisdom about How We Burn Calories

Herman Pontzer in Scientific American:

It was my daughter Clara’s seventh birthday party, a scene at once familiar and bizarre. The celebration was an American take on a classic script: a shared meal of pizza and picnic food, a few close COVID-compliant friends and family, a beaming kid blowing out candles on a heavily iced cake. With roughly 380,000 boys and girls around the world turning seven each day, it was a ritual no doubt repeated by many, the world’s most prolific primate singing “Happy Birthday” in an unbroken global chorus.

It was my daughter Clara’s seventh birthday party, a scene at once familiar and bizarre. The celebration was an American take on a classic script: a shared meal of pizza and picnic food, a few close COVID-compliant friends and family, a beaming kid blowing out candles on a heavily iced cake. With roughly 380,000 boys and girls around the world turning seven each day, it was a ritual no doubt repeated by many, the world’s most prolific primate singing “Happy Birthday” in an unbroken global chorus.

Such a wholesome setting seems an unlikely place for rampant rule breaking. But as an evolutionary anthropologist, I can’t help but notice the blatant disregard our species shows for the natural order. Nearly every aspect of our modern lives marks a cheerfully outrageous departure from the laws that govern every other species on the planet, and this birthday party was no exception. Aside from the fresh veggies left wilting in the sun, none of the food was recognizable as a product of nature. The cake was a heat-treated amalgam of pulverized grass seed, chicken eggs, cow milk and extracted beet sugar. The raw materials for the snacks and drinks would take a forensic chemist years to reconstruct. It was a calorie bonanza that animals foraging in the wild could only dream about, and we were giving it away to people who didn’t even share our genes.

More here.

Friday Poem

Lost Things, Found Hopes

For Nietzsche, hope was the beginning of loss.

But we can be even more radical:

the beginning of anything is the beginning of loss.

We all lose, but some lose more slowly

than others.

‘How’s it going?’ we ask mercilessly.

‘Slowly’, we answer, without really knowing.

Losing slowly is what we call winning.

But I, who do not love losing, love to lose myself in the forest.

Especially in forests

of music and breath,

skin and bark.

by Harkaitz Cano

from: Malgu da gaua / Flexible is the night

publisher: Etxepare Institutua, San Sebastián, 2014

How Should We Think About Our Different Styles of Thinking?

Joshua Rothman in The New Yorker:

I was nineteen, maybe twenty, when I realized I was empty-headed. I was in a college English class, and we were in a sunny seminar room, discussing “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” or possibly “The Waves.” I raised my hand to say something and suddenly realized that I had no idea what I planned to say. For a moment, I panicked. Then the teacher called on me, I opened my mouth, and words emerged. Where had they come from? Evidently, I’d had a thought—that was why I’d raised my hand. But I hadn’t known what the thought would be until I spoke it. How weird was that?

I was nineteen, maybe twenty, when I realized I was empty-headed. I was in a college English class, and we were in a sunny seminar room, discussing “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” or possibly “The Waves.” I raised my hand to say something and suddenly realized that I had no idea what I planned to say. For a moment, I panicked. Then the teacher called on me, I opened my mouth, and words emerged. Where had they come from? Evidently, I’d had a thought—that was why I’d raised my hand. But I hadn’t known what the thought would be until I spoke it. How weird was that?

Later, describing the moment to a friend, I recalled how, when I was a kid, my mother had often asked my father, “What are you thinking?” He’d shrug and say, “Nothing”—a response that irritated her to no end. (“How can he be thinking about nothing?” she’d ask me.) I’ve always been on Team Dad; I spend a lot of time thoughtless, just living life. At the same time, whenever I speak, ideas condense out of the mental cloud. It was happening even then, as I talked with my friend: I was articulating thoughts that had been unspecified yet present in my mind. My head isn’t entirely word-free; like many people, I occasionally talk to myself in an inner monologue. (Remember the milk! Ten more reps!) On the whole, though, silence reigns. Blankness, too: I see hardly any visual images, rarely picturing things, people, or places. Thinking happens as a kind of pressure behind my eyes, but I need to talk out loud in order to complete most of my thoughts.

More here.

Thursday, January 12, 2023

The Dissidents

Clayton Fox in Tablet:

Last year I spoke to a long list of leading scientists and doctors for a piece I was reporting. Of all the things they shared with me, one quote stood out:

Last year I spoke to a long list of leading scientists and doctors for a piece I was reporting. Of all the things they shared with me, one quote stood out:

There is no scientific truth, only replicable science. Then it becomes theory, but not law. And not truth. There are fundamental laws of physics that have been overturned. Law is not truth, law is law, and in science, law can be overturned.

Somehow, in the madness, fear, confusion, and paranoia of our two-year sojourn through COVID-19, that basic definition of scientific truth—that it is ever-evolving, and inimical to dogmatism—has been largely mocked, denigrated, and ignored, if not met with slogans like “believe science.”

This anti-scientific attitude has become common among scientists, too—ones who, like Dr. Anthony Fauci, assume that “attacks on me quite frankly are attacks on science.” There are the medical doctors, who are convinced that results from a single clinical trial, conducted by Pfizer, of Pfizer’s own new antiviral pill are more legitimate than hundreds of clinical trials and observational studies of existing medications not produced by Pfizer. There are scientific and medical journal editors who refuse to publish papers that they believe might undermine existing consensus, preferring instead to publish papers that must later be retracted as fraudulent. Then there are the politicians who have been curiously uninterested in the origins of a novel, mysterious, and paradigm-shifting virus, and the journalists and “fact-checkers” whose work has invariably supported ever-shifting public health wisdom, often by simply quoting press releases from the pharmaceutical companies and government agencies whose claims they’re supposed to be evaluating in the first place.

More here.

The Secret Lives of Words

John McWhorter in the New York Times:

Some time ago, I fell into conversation with a colleague about what we had been reading lately, and the person suggested that I absolutely must give Henry James’s “The Ambassadors” a try.

Some time ago, I fell into conversation with a colleague about what we had been reading lately, and the person suggested that I absolutely must give Henry James’s “The Ambassadors” a try.

The pandemic intervened, and I forgot the recommendation. But I remembered recently and picked up the novel. Frankly, despite my profound respect for the book, it was a bit of a slog. James’s writing, especially in his last few novels, is not exactly for the beach. His tapeworm sentences qualify as literary Cubism at best or obsessive obfuscation at worst. Even James once recommended reading only five pages of “The Ambassadors” at a time.

But I was struck repeatedly by the fact that, sentence structure aside, so much of the challenge posed by James’s prose is that words often had different meanings around the turn of the century than they do now. This quiet evolution of language is a facet that can be damnably hard to notice day to day, yet its importance is hard to overstate.

More here.

US government approves use of world’s first vaccine for honeybees

Oliver Milman in The Guardian:

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has granted a conditional license for a vaccine created by Dalan Animal Health, a US biotech company, to help protect honeybees from American foulbrood disease.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has granted a conditional license for a vaccine created by Dalan Animal Health, a US biotech company, to help protect honeybees from American foulbrood disease.

“Our vaccine is a breakthrough in protecting honeybees,” said Annette Kleiser, chief executive of Dalan Animal Health. “We are ready to change how we care for insects, impacting food production on a global scale.”

The vaccine, which will initially be available to commercial beekeepers, aims to curb foulbrood, a serious disease caused by the bacterium Paenibacillus larvae that can weaken and kill hives. There is currently no cure for the disease, which in parts of the US has been found in a quarter of hives, requiring beekeepers to destroy and burn any infected colonies and administer antibiotics to prevent further spread.

More here.

Ukraine and the Eclipse of Pacifism

Stephen Milder in the Boston Review:

German leaders’ vigorous efforts over the last year to better equip the Bundeswehr—and thus prove their commitment to the security of Europe—have been described as a dramatic turning point in postwar German history. Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself used such language last February to justify his pledge to take out an unprecedented €100 billion loan, which he referred to as a “special fund” for “necessary investments and armament projects.” Unwilling to leave any doubt about his commitment to strengthening the armed forces, Scholz announced that annual defense budget increases would follow. Speaking to parliament three days after the war began, Scholz justified this orgy of defense spending by arguing that the Russian invasion marked a “watershed in the history of our continent.” The claim must be understood in reference to the elephant in the German historical imagination: World War II. “Many of us,” the chancellor explained, “still remember our parents’ or grandparents’ tales of war. And for younger people it is almost inconceivable—war in Europe.” His arguments were widely accepted. By June parliament had passed the constitutional amendment required to follow through on Scholz’s plan for the huge increase in Bundeswehr funding.

German leaders’ vigorous efforts over the last year to better equip the Bundeswehr—and thus prove their commitment to the security of Europe—have been described as a dramatic turning point in postwar German history. Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself used such language last February to justify his pledge to take out an unprecedented €100 billion loan, which he referred to as a “special fund” for “necessary investments and armament projects.” Unwilling to leave any doubt about his commitment to strengthening the armed forces, Scholz announced that annual defense budget increases would follow. Speaking to parliament three days after the war began, Scholz justified this orgy of defense spending by arguing that the Russian invasion marked a “watershed in the history of our continent.” The claim must be understood in reference to the elephant in the German historical imagination: World War II. “Many of us,” the chancellor explained, “still remember our parents’ or grandparents’ tales of war. And for younger people it is almost inconceivable—war in Europe.” His arguments were widely accepted. By June parliament had passed the constitutional amendment required to follow through on Scholz’s plan for the huge increase in Bundeswehr funding.

More here.

Felix Flicker: The Physics of Magnetic Monopoles

Triangle Of Sadness

Anju Devadas in High On Films:

Two-time Palme d’Or winner, Ruben Ostlund’s sadistic comedy Triangle of Sadness is a provocative and biting class satire of wealth and beauty privilege that plays out like a social psychology experiment. This ship-borne narrative offers a carnivalesque analysis of the ultra-rich wealth hoarders and beauty influencers and arrives at the apparent theme of the savagery of human nature. Structured into three parts, the film is held together by model couple Carl (Harris Dickinson) and Yaya (the late Charlbi Dean). Originally titled Sans filter, which translates to “Without Filter,” this film utilizes grotesque and scatological humor to lampoon social hierarchies and class divide induced by the capitalist society.

Two-time Palme d’Or winner, Ruben Ostlund’s sadistic comedy Triangle of Sadness is a provocative and biting class satire of wealth and beauty privilege that plays out like a social psychology experiment. This ship-borne narrative offers a carnivalesque analysis of the ultra-rich wealth hoarders and beauty influencers and arrives at the apparent theme of the savagery of human nature. Structured into three parts, the film is held together by model couple Carl (Harris Dickinson) and Yaya (the late Charlbi Dean). Originally titled Sans filter, which translates to “Without Filter,” this film utilizes grotesque and scatological humor to lampoon social hierarchies and class divide induced by the capitalist society.

The film, which won the Palme d’Or at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival, is a satirical black comedy set against the world of fashion and the uber-rich in which we get a glimpse of social hierarchies, gender-based power dynamics, conflicting political ideologies, financial inequality, and race power structures. Like his previous anti-capitalist films Force Majeure (2014) and The Square (2017), Triangle of Sadness also satirizes the cruelties of the super-rich upper classes. Ostlund’s reversal of power dynamics and social class in which the powerful become powerless in the face of mother nature is influenced by William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, Eugene O’Neill’s Thirst, Lina Wertmüller’s Swept Away, and Bong Joon-ho Parasite.

More here. (Note: The best film of 2022! Please watch. You will not be disappointed.)

Jafar Panahi After The Ban

Mark Krotov at n+1:

PANAHI IS A FILMMAKER of exquisite efficiency, and the basic contours of No Bears are apparent from its first five minutes. Bakhtiar and Zara are in Turkey with the production, and Panahi himself—actually, let’s call him Jafar to avoid any suggestion of documentary; for all their ambiguous refractions of reality, Panahi’s films are carefully scripted—is directing a semi-documentary film based on their life remotely from a village in Iran, on the other side of the border. (Like Panahi, Jafar has been banned from leaving Iran, but he believes that relative proximity to his cast and crew is better than none at all.) As the film goes on, the particularities, intensities, and terrors of the village where Jafar is staying come into clear focus, while the film-within-a-film falls apart. If Kiarostami’s gorgeous rural compositions occasionally led critics to confuse him for someone working in a lyrical or pastoral mode, before the ban Panahi had always been too single-minded in his focus on the city to be anything other than a quintessentially urban filmmaker.

PANAHI IS A FILMMAKER of exquisite efficiency, and the basic contours of No Bears are apparent from its first five minutes. Bakhtiar and Zara are in Turkey with the production, and Panahi himself—actually, let’s call him Jafar to avoid any suggestion of documentary; for all their ambiguous refractions of reality, Panahi’s films are carefully scripted—is directing a semi-documentary film based on their life remotely from a village in Iran, on the other side of the border. (Like Panahi, Jafar has been banned from leaving Iran, but he believes that relative proximity to his cast and crew is better than none at all.) As the film goes on, the particularities, intensities, and terrors of the village where Jafar is staying come into clear focus, while the film-within-a-film falls apart. If Kiarostami’s gorgeous rural compositions occasionally led critics to confuse him for someone working in a lyrical or pastoral mode, before the ban Panahi had always been too single-minded in his focus on the city to be anything other than a quintessentially urban filmmaker.

more here.

Crimson Gold By Jafar Panahi

A Solar Land Rush In The West

Hillary Angelo at Harper’s Magazine:

In a 1947 article for this magazine, the essayist and historian Bernard DeVoto warned of the “forever-recurrent lust to liquidate the West.” “Almost invariably the first phase was a ‘rush,’ ” he wrote. “Those who participated were practically all Easterners whose sole desire was to wash out of Western soil as much wealth as they could and take it home.” For DeVoto, the New Deal offered a chance for more sustainable and locally beneficial uses of Western resources, but, in the end, Eastern capital was “able to direct much of this development in the old pattern.”

In a 1947 article for this magazine, the essayist and historian Bernard DeVoto warned of the “forever-recurrent lust to liquidate the West.” “Almost invariably the first phase was a ‘rush,’ ” he wrote. “Those who participated were practically all Easterners whose sole desire was to wash out of Western soil as much wealth as they could and take it home.” For DeVoto, the New Deal offered a chance for more sustainable and locally beneficial uses of Western resources, but, in the end, Eastern capital was “able to direct much of this development in the old pattern.”

When outsiders try to describe the solar rush, they reach for historical analogies: the 1889 Oklahoma land rush; the early-twentieth-century eucalyptus boom that tore up the desert; housing speculation and development in the Aughts. But in Beatty such boom-and-bust cycles—the sort they’ve been trying to break out of for the past ten years—are part of the everyday landscape. In the desert, the past is close to the surface.

more here.

Thursday Poem

“A 22-year-old Iranian woman died after being arrested for allegedly violating strict hijab rules — sparking protests against the Islamic Republic’s morality police.” —NY Post

Moan of the Mirror (Ahe Ayeneh)

Digging in the pit,

her family knew it was her

by her long hair.

O earth –

is this the same innocent body?

Is a woman only this pile of dirt?

She used to comb

the treasure of her hair,

and braid beyond the mirror frame

the wind of her thoughts.

She used to greet in the morning, ‘Salam!’

And her smile would pick a flower

from the reflection.

Lifting her hand to her temple

she would brush the night aside

to reveal

the sun in the mirror.

Her mind would wake on the rising day,

a rain of stars shaken loose

from the sky of her eyes,

then that sweet smile

would open a door through her reflection

onto the sun-garden of her soul.

Thieves have blinded the mirror

by stealing those eyes

from the sill of morning.

Oh you – burnt youth –

the ash of spring!

Your image has flown away from the empty mirror.

Holding the memory of your long hair

the mirror moans in the hanging dust of morning.

Birds in the garden sing for no reason.

This is no occasion for bloom.

by H.E. Sayeh

from Poetry International

Translated from the Farsi by

Chad Sweeney and Mojdeh Marashi

Wednesday, January 11, 2023

On “Jersey Breaks: Becoming an American Poet”, a memoir by Robert Pinsky

Ron Slate at On the Seawall:

Jersey Breaks is largely about insisting on having things your own way and getting away with it. Such was the example set by grandfather Dave Pinsky, Prohibition bootlegger, then bar proprietor. Young Robert was a mediocre student, or rather, he was an avid reader who spurned the orthodoxies of schooling. Music became his expressive refuge; he played the horn at school dances and later during ROTC drills at Rutgers where Paul Fussell became his first notable teacher. Before college, he read Lewis Carroll’s Alice, Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee, R. L. Stevenson, James Joyce, and Walter Scott. Then later, the first poetry – Ginsberg, Moore, Eliot, Yeats. He heard something similar in the work of Eliot and Ginsberg, though his instructors said otherwise.

More here.

In Bioethics, the Public Deserves More Than a Seat at the Table

Parmin Sedigh in Undark:

In August 2022, two research groups published papers in Nature and Cell that demonstrated scientists’ newfound ability to create synthetic mouse embryos in the laboratory until 8.5 days post-fertilization — no egg cells, sperm cells, or wombs needed. The outcry was immediate: If this can be done with mice, are humans next?

In August 2022, two research groups published papers in Nature and Cell that demonstrated scientists’ newfound ability to create synthetic mouse embryos in the laboratory until 8.5 days post-fertilization — no egg cells, sperm cells, or wombs needed. The outcry was immediate: If this can be done with mice, are humans next?

Scientists were quick to ease the public’s worries: It’s not yet possible to create synthetic human embryos. Yet their response was concerning. Why did we need to wait until such a scientific advance to occur before we could discuss its implications? How can we have important discussions about bioethical issues — issues at the intersection of ethics and biological research — that already impact society?

More here.

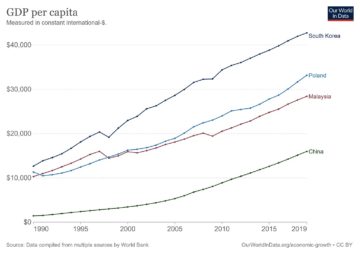

The Poland/Malaysia model: A get-upper-middle-class-quick scheme

Noah Smith in Noahpinion:

The generally acknowledged development champion of the modern world is South Korea. Joe Studwell, the author of How Asia Works, uses Korea as his paradigmatic success story, as does the economist Ha-Joon Chang (who grew up there). Chang and Studwell’s ideas have forced mainstream economists to take another look at industrial policy — in particular, at the idea that poor countries should promote manufactured exports in order to raise their productivity levels. Korea, which has fully made the transition from poverty to developed-country status over the last half century, has used this strategy to great effect. In general, in this series of posts, I’ve tried to look at developing countries through the lens of the Chang/Studwell model, which means I’ve been implicitly comparing them to South Korea all along.

The generally acknowledged development champion of the modern world is South Korea. Joe Studwell, the author of How Asia Works, uses Korea as his paradigmatic success story, as does the economist Ha-Joon Chang (who grew up there). Chang and Studwell’s ideas have forced mainstream economists to take another look at industrial policy — in particular, at the idea that poor countries should promote manufactured exports in order to raise their productivity levels. Korea, which has fully made the transition from poverty to developed-country status over the last half century, has used this strategy to great effect. In general, in this series of posts, I’ve tried to look at developing countries through the lens of the Chang/Studwell model, which means I’ve been implicitly comparing them to South Korea all along.

But anyway, South Korea is not the only big development success story that we’ve seen in recent decades. Two others that are almost as impressive are Poland and Malaysia, which are now on the cusp of developed-country status.

More here.

Sarah Sharples: Where next for self-driving vehicles?

Janelle Monáe Peels the Onion

Michael Schulman at The New Yorker:

So who is Janelle Monáe? Since she emerged on the music scene, she’s been less a pop star than a world-builder, refracting herself through sci-fi and Afrofuturist imagery. Her first EP, “Metropolis: The Chase Suite,” from 2007, drew on Fritz Lang’s German Expressionist classic and cast Monáe as her android alter ego, Cindi Mayweather. With her tuxedos and protruding pompadours, she was a glam retro-futurist androgyne, and her three studio albums—“The ArchAndroid” (2010), “The Electric Lady” (2013), and “Dirty Computer” (2018)—leaned into her funk-robot persona. “I’m a cyber-girl without a face, a heart, or a mind,” she sang on one track. Monáe used Mayweather and other spinoff characters as metaphors for her sense of otherness, as a queer Black woman from Kansas City, Kansas. (In 2018, she came out as pansexual, and last April revealed herself to be nonbinary; she uses she/her or they/them pronouns but says that her preferred pronoun is “freeassmuthafucka.”) Monaé’s forty-eight-minute visual album—or “emotion picture”—for “Dirty Computer” featured her as Jane 57821, a Sapphic android in a “Blade Runner”-esque dystopia, and in 2022 she expanded the “Dirty Computer” universe into a sci-fi story collection, “The Memory Librarian.”

So who is Janelle Monáe? Since she emerged on the music scene, she’s been less a pop star than a world-builder, refracting herself through sci-fi and Afrofuturist imagery. Her first EP, “Metropolis: The Chase Suite,” from 2007, drew on Fritz Lang’s German Expressionist classic and cast Monáe as her android alter ego, Cindi Mayweather. With her tuxedos and protruding pompadours, she was a glam retro-futurist androgyne, and her three studio albums—“The ArchAndroid” (2010), “The Electric Lady” (2013), and “Dirty Computer” (2018)—leaned into her funk-robot persona. “I’m a cyber-girl without a face, a heart, or a mind,” she sang on one track. Monáe used Mayweather and other spinoff characters as metaphors for her sense of otherness, as a queer Black woman from Kansas City, Kansas. (In 2018, she came out as pansexual, and last April revealed herself to be nonbinary; she uses she/her or they/them pronouns but says that her preferred pronoun is “freeassmuthafucka.”) Monaé’s forty-eight-minute visual album—or “emotion picture”—for “Dirty Computer” featured her as Jane 57821, a Sapphic android in a “Blade Runner”-esque dystopia, and in 2022 she expanded the “Dirty Computer” universe into a sci-fi story collection, “The Memory Librarian.”

more here.