Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

Among the resources that have been plundered by modern technology, the ruins of our attention have commanded a lot of attention. We can’t focus anymore. Getting any “deep work” done requires formidable willpower or a broken modem. Reading has degenerated into skimming and scrolling. The only real way out is to adopt a meditation practice and cultivate a monkish existence. But in actual historical fact, a life of prayer and seclusion has never meant a life without distraction. As Jamie Kreiner puts it in her new book, “The Wandering Mind,” the monks of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages (around A.D. 300 to 900) struggled mightily with attention. Connecting one’s mind to God was no easy task. The goal was “clearsighted calm above the chaos,” Kreiner writes. John of Dalyatha, an eighth-century monk who lived in what is now northern Iraq, lamented in a letter to his brother, “All I do is eat, sleep, drink and be negligent.”

Among the resources that have been plundered by modern technology, the ruins of our attention have commanded a lot of attention. We can’t focus anymore. Getting any “deep work” done requires formidable willpower or a broken modem. Reading has degenerated into skimming and scrolling. The only real way out is to adopt a meditation practice and cultivate a monkish existence. But in actual historical fact, a life of prayer and seclusion has never meant a life without distraction. As Jamie Kreiner puts it in her new book, “The Wandering Mind,” the monks of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages (around A.D. 300 to 900) struggled mightily with attention. Connecting one’s mind to God was no easy task. The goal was “clearsighted calm above the chaos,” Kreiner writes. John of Dalyatha, an eighth-century monk who lived in what is now northern Iraq, lamented in a letter to his brother, “All I do is eat, sleep, drink and be negligent.”

Kreiner, a historian at the University of Georgia, organizes the book around the various sources of distraction that a Christian monk had to face, from “the world” to the smaller “community,” all the way down to “memory” and the “mind.” Abandoning the familiar and profane was only the first step in what would turn out to be an unrelenting process — though as Kreiner explains, many monks continued to reside at home, committing themselves to lives of renunciation and prayer. For the monks who did leave, there were any number of possibilities beyond the confines of a monastery, which could pose its own distractions. Caves and deserts were obvious alternatives. Macedonius “the Pit” was partial to holes in the ground. Frange dwelled in a pharaoh’s tomb. Simeon, a “stylite,” lived on top of a pillar.

More here.

The United States has made remarkable progress over the last two years toward a future where every home is powered by clean energy. Thanks in part to historic federal investments, we’re on a path to use more clean electricity sources than ever before—including wind, solar, nuclear, and geothermal energy—which would reduce household costs, cut pollution, and diversify our energy supply so we’re not dependent on any one thing.

The United States has made remarkable progress over the last two years toward a future where every home is powered by clean energy. Thanks in part to historic federal investments, we’re on a path to use more clean electricity sources than ever before—including wind, solar, nuclear, and geothermal energy—which would reduce household costs, cut pollution, and diversify our energy supply so we’re not dependent on any one thing. The Moon doesn’t currently have an independent time. Each lunar mission uses its own timescale that is linked, through its handlers on Earth, to coordinated universal time, or

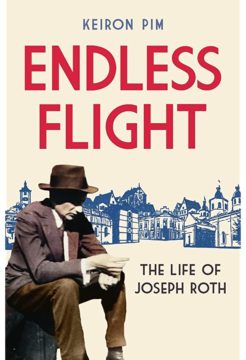

The Moon doesn’t currently have an independent time. Each lunar mission uses its own timescale that is linked, through its handlers on Earth, to coordinated universal time, or  When Joseph Roth died in penury in Paris in 1939, he left little behind. No trace of his collection of penknives, watches, walking canes and clothes bought for him by Stefan Zweig. The knives had been gathered to protect himself from both imagined and very real enemies. Soon after war’s end, his cousin visited one of his translators, Blanche Gidon, and was presented with “an old worn out coupe case”. Within it was a treasure trove ‑ some manuscripts, never published in his lifetime, books and letters. Throughout the long dark night of Nazi occupation Gidon had kept it hidden under the bed of the concierge. There have been other custodians of Roth’s reputation along the way, Hermann Kesten, a friend, and Roth’s translator, Michael Hofmann. Yet his literary significance was often ignored. Roth had been an early and vocal critic of Hitlerism. His masterpiece, The Radetsky March, had been among the first books committed for incendiary destruction when the Nazis came to power. Yet, as this magisterial biography by Kieron Pim shows, the phrase “man of many contradictions” is scarcely fit for purpose when trying to grapple with the complex contrarian Moses Joseph Roth. If Joseph Roth hadn’t been born, he’d have been invented, as a picaresque character in a novel probably by an impoverished disillusioned Mitteleuropa writer fleeing from Nazi Germany for his life.

When Joseph Roth died in penury in Paris in 1939, he left little behind. No trace of his collection of penknives, watches, walking canes and clothes bought for him by Stefan Zweig. The knives had been gathered to protect himself from both imagined and very real enemies. Soon after war’s end, his cousin visited one of his translators, Blanche Gidon, and was presented with “an old worn out coupe case”. Within it was a treasure trove ‑ some manuscripts, never published in his lifetime, books and letters. Throughout the long dark night of Nazi occupation Gidon had kept it hidden under the bed of the concierge. There have been other custodians of Roth’s reputation along the way, Hermann Kesten, a friend, and Roth’s translator, Michael Hofmann. Yet his literary significance was often ignored. Roth had been an early and vocal critic of Hitlerism. His masterpiece, The Radetsky March, had been among the first books committed for incendiary destruction when the Nazis came to power. Yet, as this magisterial biography by Kieron Pim shows, the phrase “man of many contradictions” is scarcely fit for purpose when trying to grapple with the complex contrarian Moses Joseph Roth. If Joseph Roth hadn’t been born, he’d have been invented, as a picaresque character in a novel probably by an impoverished disillusioned Mitteleuropa writer fleeing from Nazi Germany for his life. The most ambitious moment on Rat Saw God arrives via the eight-and-a-half-minute opus “

The most ambitious moment on Rat Saw God arrives via the eight-and-a-half-minute opus “ Physiologist Alejandro Caicedo of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine is preparing a grant proposal to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). He is feeling unusually stressed because of a new requirement that takes effect today. Along with his research idea, to study why islet cells in the pancreas stop making insulin in people with diabetes, he will be required to submit a plan for managing the data the project produces and sharing them in public repositories.

Physiologist Alejandro Caicedo of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine is preparing a grant proposal to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). He is feeling unusually stressed because of a new requirement that takes effect today. Along with his research idea, to study why islet cells in the pancreas stop making insulin in people with diabetes, he will be required to submit a plan for managing the data the project produces and sharing them in public repositories. I think the century will probably not belong to China or India – or any country, for that matter. Chinese achievements in the last few decades have been phenomenal, but it is now experiencing a palpable – and expected – slowdown. And while international financial media have been hyping the arrival of “India’s moment,” a cold look at the facts suggests that such assessments are premature at best.

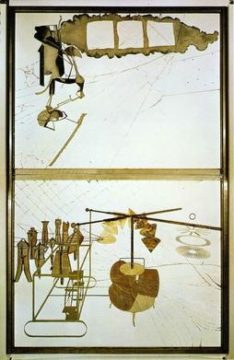

I think the century will probably not belong to China or India – or any country, for that matter. Chinese achievements in the last few decades have been phenomenal, but it is now experiencing a palpable – and expected – slowdown. And while international financial media have been hyping the arrival of “India’s moment,” a cold look at the facts suggests that such assessments are premature at best. “Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the younger brother of the sculptor Duchamp-Villon, was perhaps the most stimulating intellectual to be concerned with the visual arts in the twentieth century — ironic, witty and penetrating. He was also a born anarchist. Like his brother, he began (after some exploratory years in various current styles) with a dynamic Futurist version of Cubism, of which his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is the best known example. It caused a scandal at the famous Armory Show of modern art in New York in 1913. Duchamp’s ready-mades are everyday manufactured objects converted into works of art simply by the artist’s act of choosing them. Duchamp did nothing to them except present them for contemplation as ‘art’. They represent in many ways the most iconoclastic gesture that any artist has ever made — a gesture of total rejection and revolt against accepted artistic canons. For by reducing the creative act simply to one of choice ‘ready-mades’ discredit the ‘work of art’ and the taste, skill, craftsmanship — not to mention any higher artistic values — that it traditionally embodies. Duchamp insisted again and again that his ‘choice of these ready-mades was never dictated by an aesthetic delectation. The choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste, in fact a complete anaesthesia.’

“Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the younger brother of the sculptor Duchamp-Villon, was perhaps the most stimulating intellectual to be concerned with the visual arts in the twentieth century — ironic, witty and penetrating. He was also a born anarchist. Like his brother, he began (after some exploratory years in various current styles) with a dynamic Futurist version of Cubism, of which his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is the best known example. It caused a scandal at the famous Armory Show of modern art in New York in 1913. Duchamp’s ready-mades are everyday manufactured objects converted into works of art simply by the artist’s act of choosing them. Duchamp did nothing to them except present them for contemplation as ‘art’. They represent in many ways the most iconoclastic gesture that any artist has ever made — a gesture of total rejection and revolt against accepted artistic canons. For by reducing the creative act simply to one of choice ‘ready-mades’ discredit the ‘work of art’ and the taste, skill, craftsmanship — not to mention any higher artistic values — that it traditionally embodies. Duchamp insisted again and again that his ‘choice of these ready-mades was never dictated by an aesthetic delectation. The choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste, in fact a complete anaesthesia.’ Sigrid Undset was an unlikely literary star. Modernist themes were on the ascendancy in those days, but she wanted to write medieval romances. So at night, after work, she researched her subject, studying the sagas, old ballads, and chronicles of the Middle Ages.

Sigrid Undset was an unlikely literary star. Modernist themes were on the ascendancy in those days, but she wanted to write medieval romances. So at night, after work, she researched her subject, studying the sagas, old ballads, and chronicles of the Middle Ages.

In “Victory City,” a new novel by Salman Rushdie, a gifted storyteller and poet creates a new civilization through the sheer power of her imagination. Blessed by a goddess, she lives nearly 240 years, long enough to witness the rise and fall of her empire in southern India, but her lasting legacy is an epic poem.

In “Victory City,” a new novel by Salman Rushdie, a gifted storyteller and poet creates a new civilization through the sheer power of her imagination. Blessed by a goddess, she lives nearly 240 years, long enough to witness the rise and fall of her empire in southern India, but her lasting legacy is an epic poem. The wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 are some of the best-studied mammals on the planet. Biological technician and park ranger Rick McIntyre has spent over two decades scrutinising their daily lives, venturing into the park every single day. Where his

The wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 are some of the best-studied mammals on the planet. Biological technician and park ranger Rick McIntyre has spent over two decades scrutinising their daily lives, venturing into the park every single day. Where his  Military artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled technology might still be in the relatively fledgling stages but the debate on how to regulate its use is already in full swing. Much of the discussion revolves around autonomous weapons systems (AWS) and the ‘responsibility gap’ they would ostensibly produce. This contribution argues that while some military AI technologies may indeed cause a range of conceptual hurdles in the realm of individual responsibility, they do not raise any unique issues under the law of state responsibility. The following analysis considers the latter regime and maps out crucial junctions in applying it to potential violations of the cornerstone of international humanitarian law (IHL) – the principle of distinction – resulting from the use of AI-enabled military technologies. It reveals that any challenges in ascribing responsibility in cases involving AWS would not be caused by the incorporation of AI, but stem from pre-existing systemic shortcomings of IHL and the unclear reverberations of mistakes thereunder. The article reiterates that state responsibility for the effects of AWS deployment is always retained through the commander’s ultimate responsibility to authorise weapon deployment in accordance with IHL. It is proposed, however, that should the so-called fully autonomous weapon systems – that is, machine learning-based lethal systems that are capable of changing their own rules of operation beyond a predetermined framework – ever be fielded, it might be fairer to attribute their conduct to the fielding state, by conceptualising them as state agents, and treat them akin to state organs.

Military artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled technology might still be in the relatively fledgling stages but the debate on how to regulate its use is already in full swing. Much of the discussion revolves around autonomous weapons systems (AWS) and the ‘responsibility gap’ they would ostensibly produce. This contribution argues that while some military AI technologies may indeed cause a range of conceptual hurdles in the realm of individual responsibility, they do not raise any unique issues under the law of state responsibility. The following analysis considers the latter regime and maps out crucial junctions in applying it to potential violations of the cornerstone of international humanitarian law (IHL) – the principle of distinction – resulting from the use of AI-enabled military technologies. It reveals that any challenges in ascribing responsibility in cases involving AWS would not be caused by the incorporation of AI, but stem from pre-existing systemic shortcomings of IHL and the unclear reverberations of mistakes thereunder. The article reiterates that state responsibility for the effects of AWS deployment is always retained through the commander’s ultimate responsibility to authorise weapon deployment in accordance with IHL. It is proposed, however, that should the so-called fully autonomous weapon systems – that is, machine learning-based lethal systems that are capable of changing their own rules of operation beyond a predetermined framework – ever be fielded, it might be fairer to attribute their conduct to the fielding state, by conceptualising them as state agents, and treat them akin to state organs. Any close follower of the British media should not have been surprised that after Prince Harry fell in love with Meghan Markle, the biracial American actress, years of vitriolic, even racist coverage followed. Whipping hatred and spreading lies — including on issues far more consequential than a royal romance — is a specialty of Britain’s atrocious but politically influential tabloids.

Any close follower of the British media should not have been surprised that after Prince Harry fell in love with Meghan Markle, the biracial American actress, years of vitriolic, even racist coverage followed. Whipping hatred and spreading lies — including on issues far more consequential than a royal romance — is a specialty of Britain’s atrocious but politically influential tabloids. Crystal Mackall remembers her scepticism the first time she heard a talk about a way to engineer T cells to recognize and kill cancer. Sitting in the audience at a 1996 meeting in Germany, the paediatric oncologist turned to the person next to her and said: “No way. That’s too crazy.”

Crystal Mackall remembers her scepticism the first time she heard a talk about a way to engineer T cells to recognize and kill cancer. Sitting in the audience at a 1996 meeting in Germany, the paediatric oncologist turned to the person next to her and said: “No way. That’s too crazy.”