Julian Baggini in The Guardian:

Epicurus’s distinctive feature is his insistence that pleasure is the source of all happiness and is the only truly good thing. Hence the modern use of “epicurean” to mean gourmand. But Epicurus was no debauched hedonist. He thought the greatest pleasure was ataraxia: a state of tranquility in which we are free from anxiety. This raises the suspicion of false advertising – freedom from anxiety may be nice, but few would say it is positively pleasurable.

Epicurus’s distinctive feature is his insistence that pleasure is the source of all happiness and is the only truly good thing. Hence the modern use of “epicurean” to mean gourmand. But Epicurus was no debauched hedonist. He thought the greatest pleasure was ataraxia: a state of tranquility in which we are free from anxiety. This raises the suspicion of false advertising – freedom from anxiety may be nice, but few would say it is positively pleasurable.

Still, in a world where even the possibility of missing out inspires fear, freedom from anxiety sounds pretty attractive. How can we get it? Mainly by satisfying the right desires and ignoring the rest. Epicurus thought that desires could be natural or unnatural, and necessary or unnecessary. Our natural and necessary desires are few: healthy food, shelter, clothes, company. As long as we live in a stable, supportive community, they are easy to achieve.

We become anxious when we devote energy to pursuing things that are unnatural, unnecessary or both.

More here.

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, mutineer couturier and inexhaustible activist, had a genius for suturing extremes: rebellion and tradition, deconstruction and craft. Born Vivienne Isabel Swire in Cheshire, England, Westwood was a primary-school teacher for many years before she and her second husband, Malcolm McLaren, pioneered the styles, sounds, and attitudes that evolved into the movement known as punk. Her commitment to history and radical politics continued to infuse her work over her six-decade-long career, and when she died on December 29, age eighty-one, the world lost one of its last great iconoclasts. In the pages that follow, writer

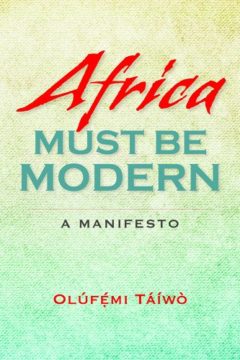

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, mutineer couturier and inexhaustible activist, had a genius for suturing extremes: rebellion and tradition, deconstruction and craft. Born Vivienne Isabel Swire in Cheshire, England, Westwood was a primary-school teacher for many years before she and her second husband, Malcolm McLaren, pioneered the styles, sounds, and attitudes that evolved into the movement known as punk. Her commitment to history and radical politics continued to infuse her work over her six-decade-long career, and when she died on December 29, age eighty-one, the world lost one of its last great iconoclasts. In the pages that follow, writer  Táíwò is a fearless and original thinker and, at times, a polemical one. To be sure, Táíwò in his ferocious mode is often witty (one chapter is called “Decolonise This!”) and scores some tidy hits, though sometimes Táíwò lets his polemical gifts carry him too far. (“Here is the deal,” he writes, “the world, the so-called West or Global North, does not owe Africa”—overlooking the many obstacles to African development, such as heavy-handed interventions in African economies by Western-dominated entities like the World Bank, and subsidies to Western farmers that price out their African counterparts.) But Táíwò’s excesses should not overshadow his insights. These are especially on display in his less scathing moments, in which he comes not to destroy decolonization but to take it over, by channeling its liberationist energies in a more productive direction. The race-based account of writers such as Mills, Táíwò points out, is complicated by colonialism’s white subjects—the Irish, Québécois and Afrikaners, for example. Many discussions of colonialism in Africa also pass over in silence what Táíwò terms “the single outstanding colonial issue in the continent,” the occupation of Western Sahara, which has been ongoing since 1975, and which features an African aggressor, Morocco. The fact that most African borders were originally drawn by colonial powers is often cited as evidence of colonialism’s ongoing presence. Táíwò counters that countries such as Nigeria, Cameroon, South Sudan and Eritrea have redrawn national borders since the colonial period, suggesting that the continent’s current borders also reflect African influence.

Táíwò is a fearless and original thinker and, at times, a polemical one. To be sure, Táíwò in his ferocious mode is often witty (one chapter is called “Decolonise This!”) and scores some tidy hits, though sometimes Táíwò lets his polemical gifts carry him too far. (“Here is the deal,” he writes, “the world, the so-called West or Global North, does not owe Africa”—overlooking the many obstacles to African development, such as heavy-handed interventions in African economies by Western-dominated entities like the World Bank, and subsidies to Western farmers that price out their African counterparts.) But Táíwò’s excesses should not overshadow his insights. These are especially on display in his less scathing moments, in which he comes not to destroy decolonization but to take it over, by channeling its liberationist energies in a more productive direction. The race-based account of writers such as Mills, Táíwò points out, is complicated by colonialism’s white subjects—the Irish, Québécois and Afrikaners, for example. Many discussions of colonialism in Africa also pass over in silence what Táíwò terms “the single outstanding colonial issue in the continent,” the occupation of Western Sahara, which has been ongoing since 1975, and which features an African aggressor, Morocco. The fact that most African borders were originally drawn by colonial powers is often cited as evidence of colonialism’s ongoing presence. Táíwò counters that countries such as Nigeria, Cameroon, South Sudan and Eritrea have redrawn national borders since the colonial period, suggesting that the continent’s current borders also reflect African influence. According to the right, a specter is haunting the United States: the specter of critical race theory (CRT).

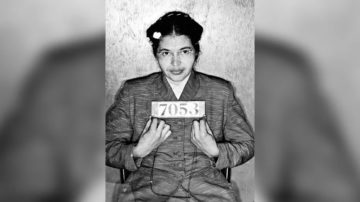

According to the right, a specter is haunting the United States: the specter of critical race theory (CRT). Every year, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) chooses the theme for

Every year, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) chooses the theme for  At first glance there is something forcibly piteous about the title of Colin Grant’s book, I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be. It reads as though there is something inherently burdensome about being Black. It isn’t until you read the full quote – “I’m black so you can do all of those white things. I’m black so you don’t have to be” – which comes from his sometime mentor and “ribald philosopher” Uncle Castus, that you understand it is not meant as a display of martyrdom, but rather an insult. It’s a jab at the privileges of the children of the Windrush generation who, hell-bent on being accepted by British society, have left the labour of Blackness to their parents.

At first glance there is something forcibly piteous about the title of Colin Grant’s book, I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be. It reads as though there is something inherently burdensome about being Black. It isn’t until you read the full quote – “I’m black so you can do all of those white things. I’m black so you don’t have to be” – which comes from his sometime mentor and “ribald philosopher” Uncle Castus, that you understand it is not meant as a display of martyrdom, but rather an insult. It’s a jab at the privileges of the children of the Windrush generation who, hell-bent on being accepted by British society, have left the labour of Blackness to their parents. Humans share elements of a common language with other apes, understanding many gestures that wild chimps and bonobos use to communicate.

Humans share elements of a common language with other apes, understanding many gestures that wild chimps and bonobos use to communicate.

In May of this past year, I

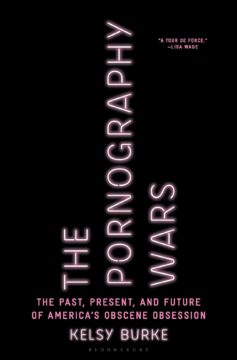

In May of this past year, I The United States’ most important smut-buster, Anthony Comstock, he of the muttonchop sideburns and perpetual scowl, was never at a loss for florid words. Describing the impact of pornography in 1883, he likened it to a cancer, one tending toward “poisoning the nature, enervating the system, destroying self-respect, fettering the will-power, defiling the mind, corrupting the thoughts, leading to secret practices of most foul and revolting character, until the victim tires of life, and existence is scarcely endurable.”

The United States’ most important smut-buster, Anthony Comstock, he of the muttonchop sideburns and perpetual scowl, was never at a loss for florid words. Describing the impact of pornography in 1883, he likened it to a cancer, one tending toward “poisoning the nature, enervating the system, destroying self-respect, fettering the will-power, defiling the mind, corrupting the thoughts, leading to secret practices of most foul and revolting character, until the victim tires of life, and existence is scarcely endurable.” On a cold, uncharacteristically dry London day in September 1931, a short, stocky man with slicked-back hair, a piercing gaze, and a hell of a lot of nerve walked along Storey’s Gate Street. He entered Central Hall, Westminster, a large assembly place near Westminster Abbey. It’s hard to imagine that this man, a thirty-seven-year-old Belgian professor of physics, did not feel some trepidation.

On a cold, uncharacteristically dry London day in September 1931, a short, stocky man with slicked-back hair, a piercing gaze, and a hell of a lot of nerve walked along Storey’s Gate Street. He entered Central Hall, Westminster, a large assembly place near Westminster Abbey. It’s hard to imagine that this man, a thirty-seven-year-old Belgian professor of physics, did not feel some trepidation. The video of the

The video of the  Here are three details I enjoy about Ace, my buddy who resides in Boulder, Utah, a speck of a town (population two hundred thirtyish) that floats atop the creamy cross-bedded Navajo Sandstone, the gargantuan petrified dunes of an Early Jurassic erg: he’s devoted the bulk of two decades to trekking the GSENM hinterlands—heating water with a twiggy fire, sipping tea, casting consciousness to the stars, reeling consciousness back in, striking camp, pushing forward; he’s eager to direct attention to the Latin phrase Solvitur ambulando (“It is solved by walking”) engraved on his pocketknife and, furthermore, assumes the phrase’s “it” requires no explanation; he’s got dogs on the rug farting and a pot of tomato sauce on the stove bubbling when—excited, hungry, fatigued from the drive (Boulder was the last municipality in the lower forty-eight to receive mail by mule and remains a long haul from anywhere)—Sophia and I arrive.

Here are three details I enjoy about Ace, my buddy who resides in Boulder, Utah, a speck of a town (population two hundred thirtyish) that floats atop the creamy cross-bedded Navajo Sandstone, the gargantuan petrified dunes of an Early Jurassic erg: he’s devoted the bulk of two decades to trekking the GSENM hinterlands—heating water with a twiggy fire, sipping tea, casting consciousness to the stars, reeling consciousness back in, striking camp, pushing forward; he’s eager to direct attention to the Latin phrase Solvitur ambulando (“It is solved by walking”) engraved on his pocketknife and, furthermore, assumes the phrase’s “it” requires no explanation; he’s got dogs on the rug farting and a pot of tomato sauce on the stove bubbling when—excited, hungry, fatigued from the drive (Boulder was the last municipality in the lower forty-eight to receive mail by mule and remains a long haul from anywhere)—Sophia and I arrive. 1990’s The Asthenic Syndrome takes us to Odesa, too, but this is an Odesa at the fraying edge of a Soviet time-space where, significantly, we never see the sea. The film is shot in places that suggest a borderland, an edge, a wobble: construction sites, mirrors, photographs, headstones, film screenings, cemeteries, a dog pound, a hospital ward, a soft-porn shoot. This in-between sense is temporal, as well: Muratova notes that she “had the great fortune of working in a period between the dominance of ideology and the dominance of the market, a period of suspension, a temporary paradise.” As with the asthenic syndrome itself (a state between sleeping and waking), the film is a realization of inbetweenness, an assembly of frictions and crossover states we feel through form: through Muratova’s use of juxtaposition; through her uncanny overpatterning of echoes and coincidences; through the shifts of register between documentary and opera. The film doesn’t proceed so much as weave itself in front of us, in a dazzling ivy pattern of zones and occurrences. You could call it late-Soviet baroque realism.

1990’s The Asthenic Syndrome takes us to Odesa, too, but this is an Odesa at the fraying edge of a Soviet time-space where, significantly, we never see the sea. The film is shot in places that suggest a borderland, an edge, a wobble: construction sites, mirrors, photographs, headstones, film screenings, cemeteries, a dog pound, a hospital ward, a soft-porn shoot. This in-between sense is temporal, as well: Muratova notes that she “had the great fortune of working in a period between the dominance of ideology and the dominance of the market, a period of suspension, a temporary paradise.” As with the asthenic syndrome itself (a state between sleeping and waking), the film is a realization of inbetweenness, an assembly of frictions and crossover states we feel through form: through Muratova’s use of juxtaposition; through her uncanny overpatterning of echoes and coincidences; through the shifts of register between documentary and opera. The film doesn’t proceed so much as weave itself in front of us, in a dazzling ivy pattern of zones and occurrences. You could call it late-Soviet baroque realism. SAN DIEGO — White caps were breaking in the bay and the rain was blowing sideways, but at Naval Base Point Loma, an elderly bottlenose dolphin named Blue was absolutely not acting her age. In a bay full of dolphins, she was impossible to miss, leaping from the water and whistling as a team of veterinarians approached along the floating docks. “She’s always really happy to see us,” said Dr. Barb Linnehan, the director of animal health and welfare at the National Marine Mammal Foundation, a nonprofit research organization. “She acts like she’s a 20-year-old dolphin.”

SAN DIEGO — White caps were breaking in the bay and the rain was blowing sideways, but at Naval Base Point Loma, an elderly bottlenose dolphin named Blue was absolutely not acting her age. In a bay full of dolphins, she was impossible to miss, leaping from the water and whistling as a team of veterinarians approached along the floating docks. “She’s always really happy to see us,” said Dr. Barb Linnehan, the director of animal health and welfare at the National Marine Mammal Foundation, a nonprofit research organization. “She acts like she’s a 20-year-old dolphin.”