Salman Rushdie in National Geographic:

The trouble with India’s Taj Mahal is that it has become so overlaid with accumulated meanings as to be almost impossible to see. A billion chocolate-box images and tourist guidebooks order us to “read” the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s marble mausoleum for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, known as “Taj Bibi,” as the World’s Greatest Monument to Love. It sits at the top of the West’s short list of images of the Exotic (and also Timeless) Orient. Like the Mona Lisa, like Andy Warhol’s silk-screened Elvis, Marilyn, and Mao, mass reproduction has all but sterilized the Taj Mahal.

The trouble with India’s Taj Mahal is that it has become so overlaid with accumulated meanings as to be almost impossible to see. A billion chocolate-box images and tourist guidebooks order us to “read” the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s marble mausoleum for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, known as “Taj Bibi,” as the World’s Greatest Monument to Love. It sits at the top of the West’s short list of images of the Exotic (and also Timeless) Orient. Like the Mona Lisa, like Andy Warhol’s silk-screened Elvis, Marilyn, and Mao, mass reproduction has all but sterilized the Taj Mahal.

Nor is this by any means a simple case of the West’s appropriation or “colonization” of an Indian masterwork. In the first place, the Taj, which in the mid-19th century had been all but abandoned and had fallen into a severe state of disrepair, would probably not be standing today were it not for the diligent conservationist efforts of the colonial British. In the second place, India is perfectly capable of over merchandising itself.

More here.

But what, exactly, is mourning, and how does doing it well contribute to a fully human life? These are good questions, addressed too rarely. In

But what, exactly, is mourning, and how does doing it well contribute to a fully human life? These are good questions, addressed too rarely. In  Colossal Biosciences, the headline-grabbing, venture-capital-funded juggernaut of de-extinction science, announced plans on January 31 to bring back the dodo. Whether “bringing back” a semblance of the extinct flightless bird is feasible is a matter of debate.

Colossal Biosciences, the headline-grabbing, venture-capital-funded juggernaut of de-extinction science, announced plans on January 31 to bring back the dodo. Whether “bringing back” a semblance of the extinct flightless bird is feasible is a matter of debate. Israel has

Israel has  Prompted in large part by the dissolution of his engagement to

Prompted in large part by the dissolution of his engagement to  Higher education in the United States is a speculative endeavor. It offers a means of inching toward something that does not quite exist but that we very badly want to realize—enlightenment, higher wages, national security. For individuals, it provides the lure of upward mobility, an illusion of escape from the lowest rungs of the labor market. For the federal government, it has charted a kind of statecraft, outlining its core commitments to military strength and economic growth, all the while absolving the state of the responsibility for ensuring that all its subjects have dignified means to live. We are told the path to decent wages and social respect must route through college.

Higher education in the United States is a speculative endeavor. It offers a means of inching toward something that does not quite exist but that we very badly want to realize—enlightenment, higher wages, national security. For individuals, it provides the lure of upward mobility, an illusion of escape from the lowest rungs of the labor market. For the federal government, it has charted a kind of statecraft, outlining its core commitments to military strength and economic growth, all the while absolving the state of the responsibility for ensuring that all its subjects have dignified means to live. We are told the path to decent wages and social respect must route through college. In her poignant essay “

In her poignant essay “ Agustin Ferrari Braun in Celebrity Studies (via Syllabus):

Agustin Ferrari Braun in Celebrity Studies (via Syllabus): Kevin P. Donovan in Boston Review:

Kevin P. Donovan in Boston Review:

Ed McNally in Sidecar:

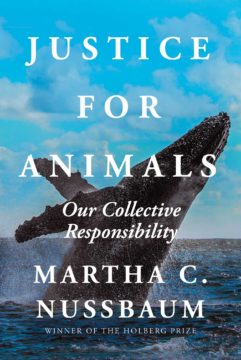

Ed McNally in Sidecar: As Justice for Animals rigorously argues, the latest scientific research reveals that the opposite is true: “all vertebrates feel pain subjectively”, many animals “experience emotions like compassion and grief” and display “complicated social learning”. For Nussbaum, the implications are “huge, clearly”. Once we recognise there’s no easy demarcation between human sentience and that of animals, “we can hardly be unchanged in our ethical thinking”.

As Justice for Animals rigorously argues, the latest scientific research reveals that the opposite is true: “all vertebrates feel pain subjectively”, many animals “experience emotions like compassion and grief” and display “complicated social learning”. For Nussbaum, the implications are “huge, clearly”. Once we recognise there’s no easy demarcation between human sentience and that of animals, “we can hardly be unchanged in our ethical thinking”. “

“ In the 20th-century U.S., black-nationalist women—individuals who advocated for black liberation, economic self-sufficiency, racial pride, unity, and political self-determination—emerged as key political leaders on the local, national, and even international levels. When most black women in the U.S. did not have access to the vote, these women boldly confronted the hypocrisy of white America, often drawing upon their knowledge of history. And they did so in public spaces—in mass community meetings, at local parks, and on sidewalks. These women harnessed the power of their voices, passion, and the raw authenticity of their political message to rally black people across the nation and the globe.

In the 20th-century U.S., black-nationalist women—individuals who advocated for black liberation, economic self-sufficiency, racial pride, unity, and political self-determination—emerged as key political leaders on the local, national, and even international levels. When most black women in the U.S. did not have access to the vote, these women boldly confronted the hypocrisy of white America, often drawing upon their knowledge of history. And they did so in public spaces—in mass community meetings, at local parks, and on sidewalks. These women harnessed the power of their voices, passion, and the raw authenticity of their political message to rally black people across the nation and the globe. Poker players have an expression for that moment when you look at your cards and discover you’ve been dealt the luckiest possible hand. It’s called “waking up with aces.” This reminds me of the way that the first lines of poems seem to come out of nowhere. It’s true for the poet, the lines just arriving, as if by dictation or angelic message — as Eliot writes in his essay on Blake, “The idea, of course, simply comes.” And it’s true for the reader, who can only have the same in medias res experience, encountering a line at the top of a page. There’s a shock to this unveiling. All the emails I get begin with some variation on “I hope this finds you well,” but a poem can begin in any kind of way. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain.” “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness.” There’s a Wallace Stevens poem that starts “Hi!”

Poker players have an expression for that moment when you look at your cards and discover you’ve been dealt the luckiest possible hand. It’s called “waking up with aces.” This reminds me of the way that the first lines of poems seem to come out of nowhere. It’s true for the poet, the lines just arriving, as if by dictation or angelic message — as Eliot writes in his essay on Blake, “The idea, of course, simply comes.” And it’s true for the reader, who can only have the same in medias res experience, encountering a line at the top of a page. There’s a shock to this unveiling. All the emails I get begin with some variation on “I hope this finds you well,” but a poem can begin in any kind of way. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain.” “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness.” There’s a Wallace Stevens poem that starts “Hi!”