Swati Sharma in Vox:

Talk about a comeback.

Talk about a comeback.

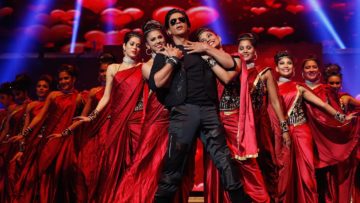

One of the biggest movie stars in the world is at one of the most tenuous moments in his career. Bollywood titan Shah Rukh Khan hasn’t made a movie in almost five years, his two most recent films failed to captivate audiences, he’s at odds with India’s ruling government, and his industry has been plagued by pandemic disruptions, boycotts from right-wing activists, and anger over nepotism. His latest film, which was released on January 25, is perhaps the biggest test of his star power in his 30-year career.

But the stakes of Khan’s movie Pathaan go far beyond the actor’s relevance. A Muslim man from a middle-class family, Khan hasn’t succumbed to the growing trend of Hindu nationalism that has dominated Bollywood for the last several years. He’s in fact been a target of the right-wing Hindutva government that has been in power since 2014, due to the charismatic star’s singular influence in India and many other parts of the world.

When the sleek high-budget action film Pathaan came out on the eve of India’s Republic Day, it became the biggest film in the world, knocking down Avatar: The Way of Water, which had held the top spot for weeks. Few predicted this level of success for the movie, but many are celebrating the beloved star’s return to the spotlight. The film has broken all sorts of records. It is one of the highest-grossing Hindi films of all time and, according to Deadline, the first Bollywood movie to earn $100 million without a release in China. It’s one thing to have huge box office numbers; it’s another to reach these kinds of milestones.

More here.

I know, I know. The value of Black history can’t be contained in only a month. And one can’t define whether a month is “good” or “bad” based on what is happening in the news cycle.

I know, I know. The value of Black history can’t be contained in only a month. And one can’t define whether a month is “good” or “bad” based on what is happening in the news cycle. If asked by someone who is unfamiliar with philosophy what they might read to begin to grasp the subject, I would recommend Thomas Nagel’s What Does It All Mean? If pressed as to why this book rather than others, my response would proceed along the following lines.

If asked by someone who is unfamiliar with philosophy what they might read to begin to grasp the subject, I would recommend Thomas Nagel’s What Does It All Mean? If pressed as to why this book rather than others, my response would proceed along the following lines. Want to become a signature voice of your nation? Try a decades-long exile in California.

Want to become a signature voice of your nation? Try a decades-long exile in California. Obesity is on the rise almost everywhere, with more overweight and obese than underweight people, globally. According to accepted wisdom, blame lies squarely with overeating and insufficient exercise. A small group of researchers is challenging such ingrained assumptions, however, and shining a spotlight on the role of chemicals in our expanding waistlines.

Obesity is on the rise almost everywhere, with more overweight and obese than underweight people, globally. According to accepted wisdom, blame lies squarely with overeating and insufficient exercise. A small group of researchers is challenging such ingrained assumptions, however, and shining a spotlight on the role of chemicals in our expanding waistlines. Friedrich Nietzsche claimed that humankind was “a fantastic animal that has to fulfil one more condition of existence than any other animal”: we have to know why we exist. Justin Gregg, a researcher into animal behaviour and cognition, agrees, describing humankind as “the why specialists” of the natural world. Our need to know the reasons behind the things we see and feel distinguishes us from other animals, who make effective decisions without ever asking why the world is as it is.

Friedrich Nietzsche claimed that humankind was “a fantastic animal that has to fulfil one more condition of existence than any other animal”: we have to know why we exist. Justin Gregg, a researcher into animal behaviour and cognition, agrees, describing humankind as “the why specialists” of the natural world. Our need to know the reasons behind the things we see and feel distinguishes us from other animals, who make effective decisions without ever asking why the world is as it is. This month at OkayAfrica, we’re celebrating Black revolution—icons and movements throughout history that have fostered revolutionary thinking and encouraged social progress. Black history is filled with an abundance of brave, era-defining artists, writers, politicians and more who’ve embodied a spirit of boldness and progressive thinking in the face of adversity. In today’s rocky political landscape of hate, misogyny and anti-blackness, these thinker’s teachings, words and ideas are invaluable. There’s no shortage of literature form the likes of Malcolm X to Steve Biko, Thomas Sankara and more that continue to spark fire in people and encourage a revolutionary spirit years after they were written. Below are 13 of our favorite books about black revolution.

This month at OkayAfrica, we’re celebrating Black revolution—icons and movements throughout history that have fostered revolutionary thinking and encouraged social progress. Black history is filled with an abundance of brave, era-defining artists, writers, politicians and more who’ve embodied a spirit of boldness and progressive thinking in the face of adversity. In today’s rocky political landscape of hate, misogyny and anti-blackness, these thinker’s teachings, words and ideas are invaluable. There’s no shortage of literature form the likes of Malcolm X to Steve Biko, Thomas Sankara and more that continue to spark fire in people and encourage a revolutionary spirit years after they were written. Below are 13 of our favorite books about black revolution. Adam Shatz on Adolfo Kaminsky in the LRB:

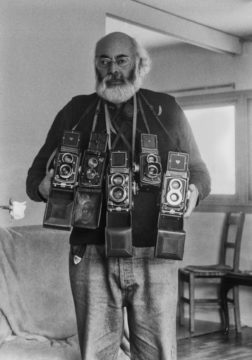

Adam Shatz on Adolfo Kaminsky in the LRB:

Jeremy Wallace in The Polycrisis:

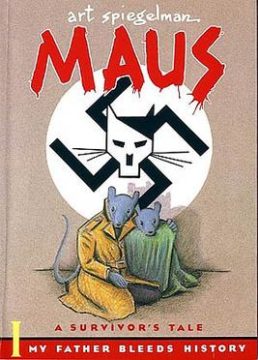

Jeremy Wallace in The Polycrisis: Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget.

Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget. Colette was not merely the most famous writer of her day, but one of the most famous people, period. A demimondaine with a shocking reputation, by the time of

Colette was not merely the most famous writer of her day, but one of the most famous people, period. A demimondaine with a shocking reputation, by the time of  On the last Friday in November, in the afterglow of a literary awards ceremony, the novelist Mieko Kawakami held court in a banquet hall at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, wearing a tweed Gucci dress, clutching an Hermès Birkin handbag and sipping a glass of domestic beer she would never quite finish. Each time she raised the drink to her lips, another writer, editor or publicist came along to distract her from it. Kawakami, who is 46, greeted them each with a degree of warmth that made it hard to tell which were strangers and which were her friends. “I’m a graduate of hostess university,” she said, recalling her years spent working at a bar where she kept men company as they drank. More than two decades later, the skills she honed in the boozy, neon-lit back alleys of Osaka — the ability to observe and to listen with acute curiosity — are still apparent in her best-selling novels. “You can see where that sensitivity arises from in her work,” the translator David Boyd told me. “She sees all the angles.”

On the last Friday in November, in the afterglow of a literary awards ceremony, the novelist Mieko Kawakami held court in a banquet hall at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, wearing a tweed Gucci dress, clutching an Hermès Birkin handbag and sipping a glass of domestic beer she would never quite finish. Each time she raised the drink to her lips, another writer, editor or publicist came along to distract her from it. Kawakami, who is 46, greeted them each with a degree of warmth that made it hard to tell which were strangers and which were her friends. “I’m a graduate of hostess university,” she said, recalling her years spent working at a bar where she kept men company as they drank. More than two decades later, the skills she honed in the boozy, neon-lit back alleys of Osaka — the ability to observe and to listen with acute curiosity — are still apparent in her best-selling novels. “You can see where that sensitivity arises from in her work,” the translator David Boyd told me. “She sees all the angles.” Centered at the Harlem neighborhood in New York City, Harlem Renaissance was an African American movement which peaked around the mid-1920s and during which African Americans took giant strides politically, socially and artistically. Known as the New Negro Movement during the time, it is most closely associated with Jazz and the rise of African American arts. Know more through the 10 most famous people associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

Centered at the Harlem neighborhood in New York City, Harlem Renaissance was an African American movement which peaked around the mid-1920s and during which African Americans took giant strides politically, socially and artistically. Known as the New Negro Movement during the time, it is most closely associated with Jazz and the rise of African American arts. Know more through the 10 most famous people associated with the Harlem Renaissance.