Joy James in The Boston Review:

Austin Reed’s The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict is startling, instructive, and disquieting. Unearthed in a 2009 Rochester, New York, estate sale and acquired by Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book Library, it is a hitherto-unknown confessional by a “free” nineteenth-century black New Yorker who spent decades of his life imprisoned. Reed’s memoir introduces readers to the misdeeds and tragedies of a career criminal who began his misadventures before the age of ten and whose first major crime was to set fire to the house of the white man to whom he had been unwillingly indentured.

Austin Reed’s The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict is startling, instructive, and disquieting. Unearthed in a 2009 Rochester, New York, estate sale and acquired by Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book Library, it is a hitherto-unknown confessional by a “free” nineteenth-century black New Yorker who spent decades of his life imprisoned. Reed’s memoir introduces readers to the misdeeds and tragedies of a career criminal who began his misadventures before the age of ten and whose first major crime was to set fire to the house of the white man to whom he had been unwillingly indentured.

Reed worked on Haunted Convict intermittently during his long years of confinement, as well as during brief interludes of freedom. Never entirely finished or published—in fact, unknown in its day—it provides a perfect example of problematic encounters with black captivity: How to be enlightened without treating as entertainment the consumption of black suffering? A historical artifact, the book holds both archive and mirror for the present antagonisms about racism, policing, and mass incarceration, contributing to the ongoing exploration and debates concerning American democracy and racial identity built upon black captivity.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

Let’s start with a wicked little paragraph. Guy Debord chose to kill himself the old-fashioned way; Jean-Luc Godard—“the dumbest Swiss Maoist of them all,” in the words of the amusing situationist-inspired slogan—turned to assisted suicide; the next provocateur of genius will no doubt opt for medicalized euthanasia. The bar, as they say, keeps dropping.

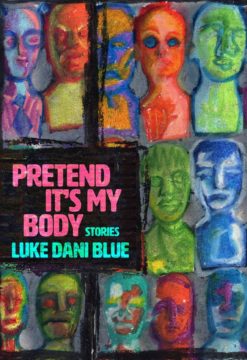

Let’s start with a wicked little paragraph. Guy Debord chose to kill himself the old-fashioned way; Jean-Luc Godard—“the dumbest Swiss Maoist of them all,” in the words of the amusing situationist-inspired slogan—turned to assisted suicide; the next provocateur of genius will no doubt opt for medicalized euthanasia. The bar, as they say, keeps dropping. JUST ANOTHER CASE of the dysphoria blues. Between online avatars, dysfunctional families, unruly Zoom rooms, and the ever-present threat of violence, the characters of Luke Dani Blue’s debut story collection Pretend It’s My Body struggle to feel at home in their bodies. Many are caught in gender friction, a stasis where change and staying the same both seem impossibly miserable. Pretend It’s My Body does not present easy narratives about relieving that friction; instead, Blue questions the way legible gender creates social mobility. This is the sticky, grim mess Blue leads us through, populated by paranoid mothers, women who may be men, and those who wish to do away with gender altogether. Apocalypse comes in small and big packages: a tornado roaring across the countryside, the Holocaust reaching Lithuania, fake shamans arguing over children, or the sun obliterating the planet as a girl goes down on her best friend who “smell[s] like sweet ruin.”

JUST ANOTHER CASE of the dysphoria blues. Between online avatars, dysfunctional families, unruly Zoom rooms, and the ever-present threat of violence, the characters of Luke Dani Blue’s debut story collection Pretend It’s My Body struggle to feel at home in their bodies. Many are caught in gender friction, a stasis where change and staying the same both seem impossibly miserable. Pretend It’s My Body does not present easy narratives about relieving that friction; instead, Blue questions the way legible gender creates social mobility. This is the sticky, grim mess Blue leads us through, populated by paranoid mothers, women who may be men, and those who wish to do away with gender altogether. Apocalypse comes in small and big packages: a tornado roaring across the countryside, the Holocaust reaching Lithuania, fake shamans arguing over children, or the sun obliterating the planet as a girl goes down on her best friend who “smell[s] like sweet ruin.” How did the world come to be? Answers to this question are called “cosmogonies” from the union of the Greek cosmos and gonos (the latter term meaning “offspring” or “creation”). Nowadays, the most authoritative answers come from scientists, whose accounts draw us back roughly 13.8 billion years ago to the Big Bang. Science’s supremacy in this regard is a relatively late development, however. For most of human history, cosmogony has been the prerogative of poets and priests. In the Theogony, for example, the ancient Greek bard Hesiod sings of Gaia (Earth) emerging from Chaos, beginning a divine family saga that stretches to Zeus’s ascendancy. The Sanskrit scriptures look back to a “golden womb” or “golden egg,” one of several embryonic beginnings found in sacred texts worldwide. And, of course, the first chapter of Genesis lays out the week that God spent putting the universe in order, giving it appropriate lighting, filling the world with life, and, in the end, taking a well-deserved day off.

How did the world come to be? Answers to this question are called “cosmogonies” from the union of the Greek cosmos and gonos (the latter term meaning “offspring” or “creation”). Nowadays, the most authoritative answers come from scientists, whose accounts draw us back roughly 13.8 billion years ago to the Big Bang. Science’s supremacy in this regard is a relatively late development, however. For most of human history, cosmogony has been the prerogative of poets and priests. In the Theogony, for example, the ancient Greek bard Hesiod sings of Gaia (Earth) emerging from Chaos, beginning a divine family saga that stretches to Zeus’s ascendancy. The Sanskrit scriptures look back to a “golden womb” or “golden egg,” one of several embryonic beginnings found in sacred texts worldwide. And, of course, the first chapter of Genesis lays out the week that God spent putting the universe in order, giving it appropriate lighting, filling the world with life, and, in the end, taking a well-deserved day off. Indeed, all living apes are found in the tropics. The oldest-known fossils from the human lineage (hominins) come from

Indeed, all living apes are found in the tropics. The oldest-known fossils from the human lineage (hominins) come from  The greater individuation of society in the post-Thatcher years, and the erosion of class as an expression of collective consciousness, has nevertheless made it easier to present poverty as a product more of moral failure than of social problems, the consequence of individual action rather than of structural inequities.

The greater individuation of society in the post-Thatcher years, and the erosion of class as an expression of collective consciousness, has nevertheless made it easier to present poverty as a product more of moral failure than of social problems, the consequence of individual action rather than of structural inequities. NORTHFIELD, WISCONSIN—

NORTHFIELD, WISCONSIN— In his generous

In his generous Almost

Almost Fascination with the ancient Egyptians seems nigh inexhaustible. And why wouldn’t it be? There are all those pyramids, so pleasingly geometric against the stark and sandy landscape. In the pyramids, in those giant tombs, massive hoards of treasure. And at the very center of those hoards of gold and bejeweled items, mummies. How can one not be fascinated by mummies? They are corpses and corpses are tantalizing. But not just any corpses, corpses of kings and queens. Death, but death preserved for centuries and eons, for eternity.

Fascination with the ancient Egyptians seems nigh inexhaustible. And why wouldn’t it be? There are all those pyramids, so pleasingly geometric against the stark and sandy landscape. In the pyramids, in those giant tombs, massive hoards of treasure. And at the very center of those hoards of gold and bejeweled items, mummies. How can one not be fascinated by mummies? They are corpses and corpses are tantalizing. But not just any corpses, corpses of kings and queens. Death, but death preserved for centuries and eons, for eternity. On the other hand, the qualities that made Tarantino the most talked about American filmmaker of his generation have also transferred cleanly into his new role as a writer of books. Quentin Tarantino is to movies what Diego Maradona was to football ‑ not just someone who does it to an exceptional level but a being entirely made of cinema, a tulpa born of the screen whose existence is ecstatically wedded to it. Tarantino has always been a joyous appreciator of movies, and the first thing to be said for his writing is that that infectious fanaticism is there on every page. The core delight of Cinema Speculation is that of being invited into the warmth of someone else’s lifelong love affair. Granted, Tarantino’s enthusiasm is so instinctively anti-hierarchical that it sometimes feels as if he has no capacity for critical discernment at all ‑ and yet, such is the enlivening force of his passion that, rather than serve as a fatal mark against him, this has quite the opposite effect. There is little he hates, or at least he has no interest in talking about anything that bores him or leaves him indifferent (bar the odd swipe at worthy 1980s fare ‑ the 1988 adaptation of Milan Kundera’s novel, he suggests, ought to have been titled The Unbearable Boredom of Watching). He ardently admires virtually every slasher movie, car-chase spectacle, heist-thriller or splatterhouse revenge-rampage ever filmed, as if discerning in each humble movie an emanation of The Movies, a divine substrate that dwells behind the screen like God beyond the skies. This boundless enthusiasm, along with that unmistakeable voice ‑ relentless, cheerful, vulgar, demotic ‑ make for attractive qualities in a writer. There’s nothing forced in Cinema Speculation; it never feels as if Tarantino is writing merely to fulfil a contractual obligation.

On the other hand, the qualities that made Tarantino the most talked about American filmmaker of his generation have also transferred cleanly into his new role as a writer of books. Quentin Tarantino is to movies what Diego Maradona was to football ‑ not just someone who does it to an exceptional level but a being entirely made of cinema, a tulpa born of the screen whose existence is ecstatically wedded to it. Tarantino has always been a joyous appreciator of movies, and the first thing to be said for his writing is that that infectious fanaticism is there on every page. The core delight of Cinema Speculation is that of being invited into the warmth of someone else’s lifelong love affair. Granted, Tarantino’s enthusiasm is so instinctively anti-hierarchical that it sometimes feels as if he has no capacity for critical discernment at all ‑ and yet, such is the enlivening force of his passion that, rather than serve as a fatal mark against him, this has quite the opposite effect. There is little he hates, or at least he has no interest in talking about anything that bores him or leaves him indifferent (bar the odd swipe at worthy 1980s fare ‑ the 1988 adaptation of Milan Kundera’s novel, he suggests, ought to have been titled The Unbearable Boredom of Watching). He ardently admires virtually every slasher movie, car-chase spectacle, heist-thriller or splatterhouse revenge-rampage ever filmed, as if discerning in each humble movie an emanation of The Movies, a divine substrate that dwells behind the screen like God beyond the skies. This boundless enthusiasm, along with that unmistakeable voice ‑ relentless, cheerful, vulgar, demotic ‑ make for attractive qualities in a writer. There’s nothing forced in Cinema Speculation; it never feels as if Tarantino is writing merely to fulfil a contractual obligation.