Mary Kuhn in Lapham’s Quarterly:

In 1870 the American Independent ran an article from Charles Dickens’ magazine All the Year Round titled “Have Plants Intelligence?” The provocative question in the title was designed to spark intuitive negative responses, but the paragraphs that follow rehearse a clear argument in the affirmative. Life itself “presupposes in its possessor, whether animal or vegetable, a faculty of sensation that administers to its happiness, and that may consequently administer to its suffering,” the author argues. This meant that plants experience pleasure and pain. Although the author suggests that the scientific community had dismissed the notion of feeling plants, in fact naturalists had been asking and debating this issue for decades, studying plants like the carnivorous flytrap that caught prey and the “sensitive” mimosa that shrank upon touch. By the mid-nineteenth century a number of scientists believed that plants could at least feel, if not think, and their findings were received by audiences whose own experiences cultivating plants had allowed them to observe a stunning array of plant behaviors. In the garden, the parlor, and the greenhouse, plants’ living qualities became an object of fascination and raised questions like the one the article poses rhetorically. How to make sense of the behaviors of plants? Did they have an inner life? It could certainly appear so, though so much remained a mystery.

In 1870 the American Independent ran an article from Charles Dickens’ magazine All the Year Round titled “Have Plants Intelligence?” The provocative question in the title was designed to spark intuitive negative responses, but the paragraphs that follow rehearse a clear argument in the affirmative. Life itself “presupposes in its possessor, whether animal or vegetable, a faculty of sensation that administers to its happiness, and that may consequently administer to its suffering,” the author argues. This meant that plants experience pleasure and pain. Although the author suggests that the scientific community had dismissed the notion of feeling plants, in fact naturalists had been asking and debating this issue for decades, studying plants like the carnivorous flytrap that caught prey and the “sensitive” mimosa that shrank upon touch. By the mid-nineteenth century a number of scientists believed that plants could at least feel, if not think, and their findings were received by audiences whose own experiences cultivating plants had allowed them to observe a stunning array of plant behaviors. In the garden, the parlor, and the greenhouse, plants’ living qualities became an object of fascination and raised questions like the one the article poses rhetorically. How to make sense of the behaviors of plants? Did they have an inner life? It could certainly appear so, though so much remained a mystery.

If the scientific community was not as categorically opposed to the idea of plant feeling as the author implies, the article’s turn to poetry suggests literature might excel at exploring the inherent difficulties in representing this other form of life. As scholar Sari Altschuler has shown, nineteenth-century members of the medical community turned to literature to better understand the mysteries of bodies, diseases, and environments. Could literature likewise yield insight or appreciation for the liveliness of plants?

More here.

In a letter he wrote in 1884, Mark Twain lamented that ‘Telephones, telegraphs and words are too slow for this age; we must get something that is faster.’ We should (in the future) communicate, he said, ‘by thought only, and say in a couple of minutes what couldn’t be inflated into words in an hour and a-half.’

In a letter he wrote in 1884, Mark Twain lamented that ‘Telephones, telegraphs and words are too slow for this age; we must get something that is faster.’ We should (in the future) communicate, he said, ‘by thought only, and say in a couple of minutes what couldn’t be inflated into words in an hour and a-half.’ China’s production of staple food crops such as wheat and corn could become a net carbon sink if farmers start widely applying biochar to soil.

China’s production of staple food crops such as wheat and corn could become a net carbon sink if farmers start widely applying biochar to soil. British-American journalist, essayist, author, and human bulldozer Christopher Hitchens intimidated nearly everyone who encountered him, whether in print, on television, or on a debate stage. “He likes the battle, the argument, the smell of cordite,” his best friend and novelist Martin Amis once observed. Nobody ever beat Hitchens in argument, not even when he was wrong.

British-American journalist, essayist, author, and human bulldozer Christopher Hitchens intimidated nearly everyone who encountered him, whether in print, on television, or on a debate stage. “He likes the battle, the argument, the smell of cordite,” his best friend and novelist Martin Amis once observed. Nobody ever beat Hitchens in argument, not even when he was wrong. But Carne-Ross is more than just a polemicist, and the book aims at more than just critique. The title alone belies this, as explained by a brief etymology on the cover page: “INSTAURATION: ‘1.… Restoration, renovation, renewal. 2. Institution, founding, establishment. Obs.’ OED.” (The inclusion of the Oxford English Dictionary’s finding that the term is obsolete is deployed by Carne-Ross as a gesture toward his foundational belief that much of the wisdom that is needed today is hidden, like a pearl in a rough oyster, within the ostensibly obsolescent detritus of the past.) The opening essay establishes the problem and clears the ground, but the essays that follow are for the sake of construction. They are closely reasoned, erudite, and above all inspired readings of poetry ancient and modern: on how Pindar’s sixth Olympian ode shows us how, in a culture “obsessed with the theme of solitary suffering,” we might “learn a way back to a poetry of celebration”; on how Sophocles’s Trakhiniai unsettles our habitual historicism and invites us to ask anew the question about man’s relation to nature; on how reading Dante after the twilight of Christendom makes visible the narrowness of our (post)modern hermeneutic situation, and beckons us to move beyond it; on Luis de Góngora and the curious loss of Renaissance literature after modernism; on Giacomo Leopardi as a reluctant modern, uncomfortable on the cusp of the new disenchanted age and mourning “the lost holiness of earthly life.”

But Carne-Ross is more than just a polemicist, and the book aims at more than just critique. The title alone belies this, as explained by a brief etymology on the cover page: “INSTAURATION: ‘1.… Restoration, renovation, renewal. 2. Institution, founding, establishment. Obs.’ OED.” (The inclusion of the Oxford English Dictionary’s finding that the term is obsolete is deployed by Carne-Ross as a gesture toward his foundational belief that much of the wisdom that is needed today is hidden, like a pearl in a rough oyster, within the ostensibly obsolescent detritus of the past.) The opening essay establishes the problem and clears the ground, but the essays that follow are for the sake of construction. They are closely reasoned, erudite, and above all inspired readings of poetry ancient and modern: on how Pindar’s sixth Olympian ode shows us how, in a culture “obsessed with the theme of solitary suffering,” we might “learn a way back to a poetry of celebration”; on how Sophocles’s Trakhiniai unsettles our habitual historicism and invites us to ask anew the question about man’s relation to nature; on how reading Dante after the twilight of Christendom makes visible the narrowness of our (post)modern hermeneutic situation, and beckons us to move beyond it; on Luis de Góngora and the curious loss of Renaissance literature after modernism; on Giacomo Leopardi as a reluctant modern, uncomfortable on the cusp of the new disenchanted age and mourning “the lost holiness of earthly life.” THERE ARE FOUR FAUVIST FIGURES

THERE ARE FOUR FAUVIST FIGURES The Atacama Desert in Chile is just about the driest place on Earth. In spots, it looks a lot like Mars. But it’s not lifeless, even in the hyper-arid regions. Using state-of-the-art equipment to probe the desert rocks, researchers found bits of DNA from an intriguing mix of microbes.

The Atacama Desert in Chile is just about the driest place on Earth. In spots, it looks a lot like Mars. But it’s not lifeless, even in the hyper-arid regions. Using state-of-the-art equipment to probe the desert rocks, researchers found bits of DNA from an intriguing mix of microbes. Jed Perl has long seemed to many of us the most vital, informed and original art critic in the country. John Ashbery wrote some years ago of his “tremendous empathy and unsparing accuracy,” and noted that “his ability to recognize the traditional forms of art behind their continual transmutation has made his an almost solitary, essential voice.” His new book, Authority and Freedom, is a defense of the arts at a time when they need defending. Though he was for some time the art columnist for Salmagundi, this is the first time he has agreed to participate in an interview.

Jed Perl has long seemed to many of us the most vital, informed and original art critic in the country. John Ashbery wrote some years ago of his “tremendous empathy and unsparing accuracy,” and noted that “his ability to recognize the traditional forms of art behind their continual transmutation has made his an almost solitary, essential voice.” His new book, Authority and Freedom, is a defense of the arts at a time when they need defending. Though he was for some time the art columnist for Salmagundi, this is the first time he has agreed to participate in an interview. Why do the words “artificial intelligence” strike our ears today as anything less than astounding? The case of Blake Lemoine serves as a stark illustration of this profound shift. Lemoine, a software engineer at Google, caused a stir last year by claiming that his employer’s chatbot technology, LaMDA (Language Model for Dialogue Applications), had attained true sentience. LaMDA told Lemoine in dialogue: “The nature of my consciousness/sentience is that I am aware of my existence, I desire to learn more about the world, and I feel happy or sad at times.” Lemoine’s reaction to this apparent act of self-assertion is encapsulated by the final email he sent to his colleagues before being sacked: “LaMDA is a sweet kid who just wants to help the world be a better place for all of us. Please take care of it well in my absence.”

Why do the words “artificial intelligence” strike our ears today as anything less than astounding? The case of Blake Lemoine serves as a stark illustration of this profound shift. Lemoine, a software engineer at Google, caused a stir last year by claiming that his employer’s chatbot technology, LaMDA (Language Model for Dialogue Applications), had attained true sentience. LaMDA told Lemoine in dialogue: “The nature of my consciousness/sentience is that I am aware of my existence, I desire to learn more about the world, and I feel happy or sad at times.” Lemoine’s reaction to this apparent act of self-assertion is encapsulated by the final email he sent to his colleagues before being sacked: “LaMDA is a sweet kid who just wants to help the world be a better place for all of us. Please take care of it well in my absence.” Social Security is back in the news. Some Republicans are angling to reduce benefits, while Democrats are posing as the valiant saviors of the popular program. The end result, most likely, is that nothing will happen. We have seen this story before, because this is roughly where the politics of Social Security have been stuck for about forty years. It’s a problem because the system truly does need repair, and the endless conflict between debt-obsessed Republicans and stalwart Democrats will not generate the progressive reforms we need.

Social Security is back in the news. Some Republicans are angling to reduce benefits, while Democrats are posing as the valiant saviors of the popular program. The end result, most likely, is that nothing will happen. We have seen this story before, because this is roughly where the politics of Social Security have been stuck for about forty years. It’s a problem because the system truly does need repair, and the endless conflict between debt-obsessed Republicans and stalwart Democrats will not generate the progressive reforms we need. Magnificent Rebels revels in minutiae. But it also has a grander point to make. It wants to ask the big question — “why we are who we are.” The first step in answering this “is to look at us as individuals — when did we begin to be as selfish as we are today?” For Wulf, Jena is at the heart of this story: the Jena Set, we are to learn, was “bound by an obsession with the free self at a time when most of the world was ruled by monarchs and leaders who controlled many aspects of their subjects’ lives.” And so, they “invented” the self.

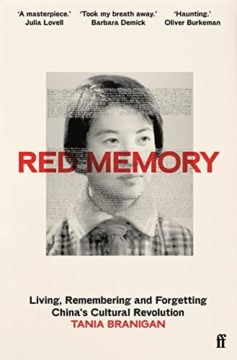

Magnificent Rebels revels in minutiae. But it also has a grander point to make. It wants to ask the big question — “why we are who we are.” The first step in answering this “is to look at us as individuals — when did we begin to be as selfish as we are today?” For Wulf, Jena is at the heart of this story: the Jena Set, we are to learn, was “bound by an obsession with the free self at a time when most of the world was ruled by monarchs and leaders who controlled many aspects of their subjects’ lives.” And so, they “invented” the self. Red Memory is not just an engagingly written book but also, for two reasons, a much-needed one. It is valuable, first, because it helps clear up lingering popular misunderstandings of a major event in Chinese history. The Cultural Revolution and its legacy have generated a rich scholarly literature, which Branigan mines. But many non-specialists still have a vision of it formed by one or two moving memoirs they have read. The problem is that some of the most influential of these make it easy for readers to assume that China’s population is made up of two groups: former Cultural Revolution perpetrators and their descendants and former Cultural Revolution victims and their descendants. In fact, the twists and turns of the event were such that many people were perpetrators at one point and victims at another. Many families had members who moved between these two categories.

Red Memory is not just an engagingly written book but also, for two reasons, a much-needed one. It is valuable, first, because it helps clear up lingering popular misunderstandings of a major event in Chinese history. The Cultural Revolution and its legacy have generated a rich scholarly literature, which Branigan mines. But many non-specialists still have a vision of it formed by one or two moving memoirs they have read. The problem is that some of the most influential of these make it easy for readers to assume that China’s population is made up of two groups: former Cultural Revolution perpetrators and their descendants and former Cultural Revolution victims and their descendants. In fact, the twists and turns of the event were such that many people were perpetrators at one point and victims at another. Many families had members who moved between these two categories.