Morgan Meis in The New Yorker:

I often watch the television show “Hoarders.” One of my favorite episodes features the pack rats Patty and Debra. Patty is a typical trash-and-filth hoarder: her bathroom contains horrors I’d rather not describe, and her story follows the show’s typical arc of reform and redemption. But Debra, who hoards clothes, home decorations, and tchotchkes, is more unusual. She doesn’t believe that she has a problem; in fact, she’s completely unimpressed by the producers’ efforts to fix her house. “It’s just not my color, white,” she says, walking through her newly de-hoarded rooms. “Everything that I really loved in my house is gone.” She is unrepentant, concluding, “This is horrible—I hate it!” Debra just loves to hoard, and people who want her to stop don’t get it.

I often watch the television show “Hoarders.” One of my favorite episodes features the pack rats Patty and Debra. Patty is a typical trash-and-filth hoarder: her bathroom contains horrors I’d rather not describe, and her story follows the show’s typical arc of reform and redemption. But Debra, who hoards clothes, home decorations, and tchotchkes, is more unusual. She doesn’t believe that she has a problem; in fact, she’s completely unimpressed by the producers’ efforts to fix her house. “It’s just not my color, white,” she says, walking through her newly de-hoarded rooms. “Everything that I really loved in my house is gone.” She is unrepentant, concluding, “This is horrible—I hate it!” Debra just loves to hoard, and people who want her to stop don’t get it.

I was never sure why Debra’s stubbornness fascinated me until I came across the work of Jane Bennett, a philosopher and political theorist at Johns Hopkins. A few years ago, while delivering a lecture, Bennett played clips from “Hoarders,” commenting on them in detail. She is sympathetic to people like Debra, partly because, like the hoarders themselves, she is focussed on the hoard. She has philosophical questions about it. Why are these objects so alluring? What are they “trying” to do? We tend to think of the show’s hoards as inert, attributing blame, influence, and the possibility of redemption to the human beings who create them. But what if the hoard, as Bennett asked in her lecture, has more agency than that? What if these piles of junk exert some power of their own?

More here.

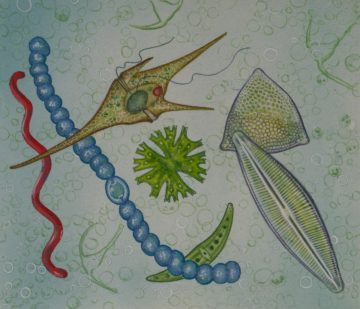

The defining feature of our world is life. For all we know, Earth is the only planet with life on it. Despite our age of environmental destruction, there’s life in every corner of the globe, under its water, nestled in the most extreme environments we can imagine. But why? How did life start on Earth? What was the series of events that led to birds, bugs, amoebas, you, and me? That’s the subject of Origins, a three-episode series from

The defining feature of our world is life. For all we know, Earth is the only planet with life on it. Despite our age of environmental destruction, there’s life in every corner of the globe, under its water, nestled in the most extreme environments we can imagine. But why? How did life start on Earth? What was the series of events that led to birds, bugs, amoebas, you, and me? That’s the subject of Origins, a three-episode series from  Emotions such as fear and

Emotions such as fear and  What is the matter with theory? More specifically, what does a distinctively modern approach to theorizing have to do with the prevalence of the kind of conspiracist thinking that thrives in our era of post-truth politics? To find answers to that question, political and cultural analysts have recently returned to the work of Hannah Arendt—and for good reason. Despite her training as a philosopher in her native Germany, the brilliant Jewish émigré thinker (1906–75) was not only not a theorist but even something of an anti-theorist, a practitioner of exercises of political thinking that were never theoretical in the usual sense. Ranging from her magisterial Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition to her many essays, reviews, and works of analytical reportage (notably in Eichmann in Jerusalem), her oeuvre might best be characterized as a form of praxis, of thought in action. Grounded in the common world, this form of political thinking aims to support continued and active engagement in that world.

What is the matter with theory? More specifically, what does a distinctively modern approach to theorizing have to do with the prevalence of the kind of conspiracist thinking that thrives in our era of post-truth politics? To find answers to that question, political and cultural analysts have recently returned to the work of Hannah Arendt—and for good reason. Despite her training as a philosopher in her native Germany, the brilliant Jewish émigré thinker (1906–75) was not only not a theorist but even something of an anti-theorist, a practitioner of exercises of political thinking that were never theoretical in the usual sense. Ranging from her magisterial Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition to her many essays, reviews, and works of analytical reportage (notably in Eichmann in Jerusalem), her oeuvre might best be characterized as a form of praxis, of thought in action. Grounded in the common world, this form of political thinking aims to support continued and active engagement in that world. Why did I want a Californian? Well, that was not exactly what I wrote, although I appreciated the headline writer’s teasing provocation. What I did write was that the next pope should be “a bit of a Californian.” I opened the piece by quoting the novelist Walker Percy’s cantankerous assertion that Catholics had to choose between “either Rome or California.” In Percy’s mind, California stood for everything alienating, dehumanizing, and spiritually moribund in modern life, while Roman Catholicism offered the true, if demanding, path to human flourishing. I thought that was a false choice. The Church would have to come to terms with everything California represented; retreating from the modern world was not an option. “Rome is no refuge; it never has been, and as recent scandals remind us, never could be,” I wrote. “Yet Rome has much missionary work to do—in California and elsewhere. That work will require a change in tone and a refusal to condemn what it cannot yet understand.” In conclusion, I quoted the philosopher Charles Taylor. Rome proposes “too many answers choking off questions and too little sense of the enigmas that accompany a life of faith; these are what stop a conversation from ever starting between our Church and much of our world.”

Why did I want a Californian? Well, that was not exactly what I wrote, although I appreciated the headline writer’s teasing provocation. What I did write was that the next pope should be “a bit of a Californian.” I opened the piece by quoting the novelist Walker Percy’s cantankerous assertion that Catholics had to choose between “either Rome or California.” In Percy’s mind, California stood for everything alienating, dehumanizing, and spiritually moribund in modern life, while Roman Catholicism offered the true, if demanding, path to human flourishing. I thought that was a false choice. The Church would have to come to terms with everything California represented; retreating from the modern world was not an option. “Rome is no refuge; it never has been, and as recent scandals remind us, never could be,” I wrote. “Yet Rome has much missionary work to do—in California and elsewhere. That work will require a change in tone and a refusal to condemn what it cannot yet understand.” In conclusion, I quoted the philosopher Charles Taylor. Rome proposes “too many answers choking off questions and too little sense of the enigmas that accompany a life of faith; these are what stop a conversation from ever starting between our Church and much of our world.” Last week,

Last week,  Viruses are notorious as scourges of cellular life, destroying as ruthlessly as any predator. Yet as microbiologists are now piecing together, these killers also sometimes perish as prey.

Viruses are notorious as scourges of cellular life, destroying as ruthlessly as any predator. Yet as microbiologists are now piecing together, these killers also sometimes perish as prey. Riley Moore: It’s difficult to discuss Aristotle without discussing everything, because Aristotle wrote about everything—ethics, logic, biology, politics, literature; anything knowable, he investigated it. You go through this in detail in your newest book, Aristotle: Understanding the World’s Greatest Philosopher. Let’s pretend I have never heard of Aristotle. Who was Aristotle, biographically? Was he a pupil of Plato just as Plato was a pupil of Socrates? Is there a direct lineage there?

Riley Moore: It’s difficult to discuss Aristotle without discussing everything, because Aristotle wrote about everything—ethics, logic, biology, politics, literature; anything knowable, he investigated it. You go through this in detail in your newest book, Aristotle: Understanding the World’s Greatest Philosopher. Let’s pretend I have never heard of Aristotle. Who was Aristotle, biographically? Was he a pupil of Plato just as Plato was a pupil of Socrates? Is there a direct lineage there? W

W Billions of years ago, before there were beasts, bacteria or any living organism, there were RNAs. These molecules were probably swirling around with amino acids and other rudimentary biomolecules, merging and diverging, on an otherwise lifeless crucible of a planet.

Billions of years ago, before there were beasts, bacteria or any living organism, there were RNAs. These molecules were probably swirling around with amino acids and other rudimentary biomolecules, merging and diverging, on an otherwise lifeless crucible of a planet. According to a familiar story, science was born as a pastime of seventeenth-century European gentlemen, who built air pumps, traded telescopes, and measured everything from the size of the earth to the eye of a fly as they sought to uncover the laws of nature. Through careful experimentation and observation of nature, these men—who called themselves natural philosophers—distinguished themselves from the scholastic schoolmen of yore, who had instead busied themselves with writing commentary upon commentary on Aristotle and Aquinas. They also wrote about themselves. They formed societies, took notes at their meetings, compiled their notes into journals, and penned books recording their achievements; it was a mere seven years after the founding of the Royal Society in 1660 that Thomas Sprat published its first history. Reason had finally come into its own, and it arrived with a diligent group of stenographers.

According to a familiar story, science was born as a pastime of seventeenth-century European gentlemen, who built air pumps, traded telescopes, and measured everything from the size of the earth to the eye of a fly as they sought to uncover the laws of nature. Through careful experimentation and observation of nature, these men—who called themselves natural philosophers—distinguished themselves from the scholastic schoolmen of yore, who had instead busied themselves with writing commentary upon commentary on Aristotle and Aquinas. They also wrote about themselves. They formed societies, took notes at their meetings, compiled their notes into journals, and penned books recording their achievements; it was a mere seven years after the founding of the Royal Society in 1660 that Thomas Sprat published its first history. Reason had finally come into its own, and it arrived with a diligent group of stenographers. To successfully navigate their world, organisms rely on numerous senses. Birds are no exception to this; and yet, for a long time, people have been convinced that birds cannot smell. This came as a surprise to evolutionary biologist Danielle J. Whittaker. Given that smell is effectively chemoreception (the sensing of chemical gradients in your environment) and was

To successfully navigate their world, organisms rely on numerous senses. Birds are no exception to this; and yet, for a long time, people have been convinced that birds cannot smell. This came as a surprise to evolutionary biologist Danielle J. Whittaker. Given that smell is effectively chemoreception (the sensing of chemical gradients in your environment) and was  At turns hilariously absurd and gut-wrenchingly heartfelt, Terese Svoboda’s Dog on Fire, published by the University of Nebraska Press, defies genre. Svoboda juggles comedy, mystery, tragedy, horror—and masters them all. The book follows a recently-divorced woman grieving the mysterious and early death of her estranged brother. Her unusual circumstances lead her to move back to her small Midwestern home town, where everything and anything she does creates ripples of rumor. There, she confronts perilous Halloween parties, Jell-O inventions, guns, grave-diggers, and, of course, dogs on fire.

At turns hilariously absurd and gut-wrenchingly heartfelt, Terese Svoboda’s Dog on Fire, published by the University of Nebraska Press, defies genre. Svoboda juggles comedy, mystery, tragedy, horror—and masters them all. The book follows a recently-divorced woman grieving the mysterious and early death of her estranged brother. Her unusual circumstances lead her to move back to her small Midwestern home town, where everything and anything she does creates ripples of rumor. There, she confronts perilous Halloween parties, Jell-O inventions, guns, grave-diggers, and, of course, dogs on fire. G

G