Anthony Curtis Adler at the LARB:

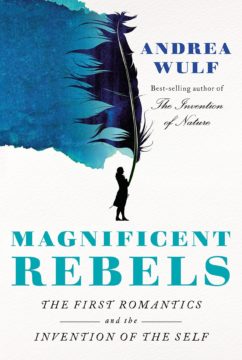

Magnificent Rebels revels in minutiae. But it also has a grander point to make. It wants to ask the big question — “why we are who we are.” The first step in answering this “is to look at us as individuals — when did we begin to be as selfish as we are today?” For Wulf, Jena is at the heart of this story: the Jena Set, we are to learn, was “bound by an obsession with the free self at a time when most of the world was ruled by monarchs and leaders who controlled many aspects of their subjects’ lives.” And so, they “invented” the self.

Magnificent Rebels revels in minutiae. But it also has a grander point to make. It wants to ask the big question — “why we are who we are.” The first step in answering this “is to look at us as individuals — when did we begin to be as selfish as we are today?” For Wulf, Jena is at the heart of this story: the Jena Set, we are to learn, was “bound by an obsession with the free self at a time when most of the world was ruled by monarchs and leaders who controlled many aspects of their subjects’ lives.” And so, they “invented” the self.

It is, however, precisely in addressing this grander question that Magnificent Rebels fails most magnificently. While Fichte’s radical attempt to ground Immanuel Kant’s philosophy in the self-and-other-positing “I” is reduced to a caricature, this very caricature carries Wulf’s entire argument: it justifies her in conceiving the self as an invention, and of understanding the egoism and narcissism of her extravagant characters as practical Fichteanism. Fichte, however, did not invent the self; rather, he invented the idea of the transcendental self as the self-positing, self-inventing, radically inventive ground of the empirical self. Friedrich Schlegel, Schelling, and Novalis, as well as Hölderlin and Hegel, were all, to be sure, deeply influenced by Fichte, but they also almost immediately recognized the one-sidedness of his early system.

more here.