From Smithsonian:

Coppery like a penny, thick like bad molasses, even a little gamey like a possum.

Coppery like a penny, thick like bad molasses, even a little gamey like a possum.

The white conductor’s blood in her mouth probably didn’t taste good, but it probably didn’t taste bad, either. Ida B. Wells sat firmly while the Memphis streetcar man gripped her body and tried to forcibly remove her from the first-class ladies car on a train from the Poplar Station to northern Shelby County in Tennessee. Wells—a prominent Black journalist and activist—took a bite out of the guy until he “bled freely,” he would later testify in court. After the conductor successfully dragged Wells off the train, she sued the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwestern Railroad Company for failing to provide “separate but equal” accommodations for Black and white passengers. She won the case and received a $500 settlement, but the ruling was ultimately overturned by the state Supreme Court.

Wells occupied that seat on September 15, 1883. Born about an hour southeast in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1862, she’d lost her parents and young brother to the devastating 1878 yellow fever epidemic. Her parents were involved with Reconstruction-era politics and the democratization of education; their daughter would carry on that mantle as a radical teacher in her own right. She studied at the historically Black Shaw University (now Rust College), then took summer classes at Fisk University in Nashville and LeMoyne-Owen College in Memphis.

More here.

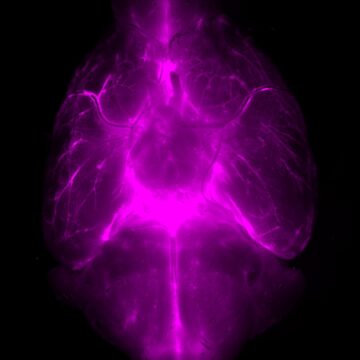

We all need sleep, but no one really knows why. For the past 10 years, a prevailing theory has been that a key function of sleep is to

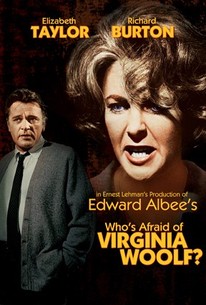

We all need sleep, but no one really knows why. For the past 10 years, a prevailing theory has been that a key function of sleep is to  Cocktails with George and Martha is a dishy, process-heavy appreciation of a cinematic masterpiece. Gefter shows how, after almost 60 years, the kitchen-sink savagery of the movie—and Edward Albee’s 1962 play, on which it is based—still shatters. The film portrays a long, cocktail-infused Saturday night at the home of middle-aged history professor George (played by Richard Burton in the movie) and his wife, Martha (Elizabeth Taylor). Martha has invited another couple over for drinks, with whom they begin to bicker, then flirt, then wage war. Their heaviest weapon is their imaginary child (they are, in fact, childless), whom they use as a punching bag and a life raft. Gefter locates Albee’s genius in the creation of the child and his poetic language, but also in the tender ending, which suggests that for George and Martha, at least, the sparring has been play-acting, albeit of the most serious kind.

Cocktails with George and Martha is a dishy, process-heavy appreciation of a cinematic masterpiece. Gefter shows how, after almost 60 years, the kitchen-sink savagery of the movie—and Edward Albee’s 1962 play, on which it is based—still shatters. The film portrays a long, cocktail-infused Saturday night at the home of middle-aged history professor George (played by Richard Burton in the movie) and his wife, Martha (Elizabeth Taylor). Martha has invited another couple over for drinks, with whom they begin to bicker, then flirt, then wage war. Their heaviest weapon is their imaginary child (they are, in fact, childless), whom they use as a punching bag and a life raft. Gefter locates Albee’s genius in the creation of the child and his poetic language, but also in the tender ending, which suggests that for George and Martha, at least, the sparring has been play-acting, albeit of the most serious kind. Imagine a machine that provides a simulation of any experience a person might want, but once the machine is activated, the person is unable to tell that the experience isn’t real. When Robert Nozick formulated this thought experiment in 1974, it was meant to be obvious that people in otherwise ordinary circumstances would be making a horrible mistake if they hooked themselves up to such a machine permanently. During the intervening decades, however, cultural commitment to that core value — the value of being in contact with reality as it is — has become more tenuous, and the empathic use of AI, in which people seek to be understood, cared for and even loved by a large language model (LLM), is on the rise.

Imagine a machine that provides a simulation of any experience a person might want, but once the machine is activated, the person is unable to tell that the experience isn’t real. When Robert Nozick formulated this thought experiment in 1974, it was meant to be obvious that people in otherwise ordinary circumstances would be making a horrible mistake if they hooked themselves up to such a machine permanently. During the intervening decades, however, cultural commitment to that core value — the value of being in contact with reality as it is — has become more tenuous, and the empathic use of AI, in which people seek to be understood, cared for and even loved by a large language model (LLM), is on the rise. Some 60,000 years ago, Neanderthals in western Eurasia acquired strange new neighbours: a wave of Homo sapiens migrants making their way out of Africa, en route to future global dominance. Now, a study

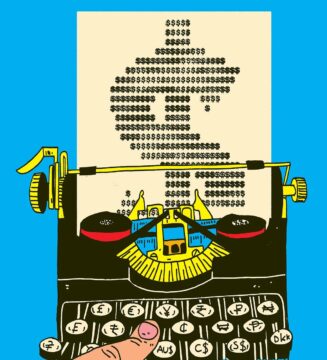

Some 60,000 years ago, Neanderthals in western Eurasia acquired strange new neighbours: a wave of Homo sapiens migrants making their way out of Africa, en route to future global dominance. Now, a study Imagine that in every business school students were told, in all seriousness, that they were in training for being a billionaire. Imagine it was heavily implied that the natural conclusion of their careers—what “making it” in business meant—was legit billionaire-status. Judged from the outside, such a situation would appear the enactment of a collective pathological delusion.

Imagine that in every business school students were told, in all seriousness, that they were in training for being a billionaire. Imagine it was heavily implied that the natural conclusion of their careers—what “making it” in business meant—was legit billionaire-status. Judged from the outside, such a situation would appear the enactment of a collective pathological delusion. IN AN

IN AN  Friends called her Anna Vassilievna, according to the Russian custom of having the patronym follow the given name. As evening fell, I often lay in my child’s pyjamas, on the living room sofa, close to my grandmother, my Babushka. The sofa stood in our living room in the Leipzig apartment, close to the large window. Some light came from the outside.

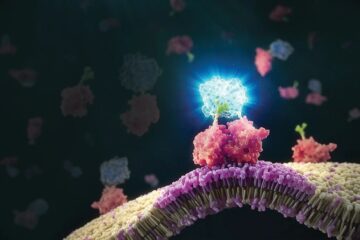

Friends called her Anna Vassilievna, according to the Russian custom of having the patronym follow the given name. As evening fell, I often lay in my child’s pyjamas, on the living room sofa, close to my grandmother, my Babushka. The sofa stood in our living room in the Leipzig apartment, close to the large window. Some light came from the outside. Although chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T therapy — where a patient’s T cells are engineered to fight cancer — works well against blood cancers in young people, that success drops dramatically for older patients. The impact of ageing on an older patient’s T cells, so-called cell fitness, could be the problem.

Although chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T therapy — where a patient’s T cells are engineered to fight cancer — works well against blood cancers in young people, that success drops dramatically for older patients. The impact of ageing on an older patient’s T cells, so-called cell fitness, could be the problem. For the first half of my life, certainly, when I was in my twenties, I was a great disappointment to my parents. College had held no interest for me. I was threatened that I had such a bad record of attendance at Hindu College that I would not be allowed to sit for my final-year exams. Each morning I boarded the University Special, the shuttle bus that the DTC provided for students, but I did so with the sole aim of sitting close to a girl I liked. (In three years, the sum total of our conversation had gone like this: “Would you like to read my poems?” “No.”) Then, I fell in love with another woman, from a different year, a year junior to me. I wrote her many letters, and even received responses, but we spent very little time together. We never even held hands. But I was happy. Instead of going to class, I sat on the college lawns smoking cigarettes, or reading in various libraries in the city, discovering poetry and fiction.

For the first half of my life, certainly, when I was in my twenties, I was a great disappointment to my parents. College had held no interest for me. I was threatened that I had such a bad record of attendance at Hindu College that I would not be allowed to sit for my final-year exams. Each morning I boarded the University Special, the shuttle bus that the DTC provided for students, but I did so with the sole aim of sitting close to a girl I liked. (In three years, the sum total of our conversation had gone like this: “Would you like to read my poems?” “No.”) Then, I fell in love with another woman, from a different year, a year junior to me. I wrote her many letters, and even received responses, but we spent very little time together. We never even held hands. But I was happy. Instead of going to class, I sat on the college lawns smoking cigarettes, or reading in various libraries in the city, discovering poetry and fiction. The Obama administration saw a flurry of tech sector hype about self-driving cars. Not being a technical person, I had no ability to assess the hype on the merits, but companies were putting real money into it, and so I wrote pieces looking at the labor market, land use, and transportation policy implications. But the tech turned out to be way overhyped, progress was much slower than advertised, and then Elon Musk further poisoned the water by marketing some limited (albeit impressive) self-driving software as “Full Self-Driving.”

The Obama administration saw a flurry of tech sector hype about self-driving cars. Not being a technical person, I had no ability to assess the hype on the merits, but companies were putting real money into it, and so I wrote pieces looking at the labor market, land use, and transportation policy implications. But the tech turned out to be way overhyped, progress was much slower than advertised, and then Elon Musk further poisoned the water by marketing some limited (albeit impressive) self-driving software as “Full Self-Driving.” In 2017, strategic studies scholar Brahma Chellaney

In 2017, strategic studies scholar Brahma Chellaney  There’s the crux of the issue: the k-hole. Ketamine gets you really, elaborately, bizarrely high. Doctors have never quite known how to describe this high or what to do about it. During the drug’s clinical trials in 1964, recovering patients reported that they’d been dead, suspended among the stars, or living in a movie. One researcher observed that ketamine “produced ‘zombies’ who were totally disconnected from their environment.” Investigators had to find the right word to broach these effects; hallucinations and zombies wouldn’t go over well with the FDA. An early contender, schizophrenomimetic (i.e., mimicking schizophrenia), was tossed out for obvious reasons. They settled on dissociative, which suggested a gossamer untethering of body and brain. A hot air balloon dissociates from the earth; the two halves of a Venn diagram are a dissociated circle. Confusingly, there was already a long history of dissociation in psychology, where the word describes someone too detached from reality to function. Dissociative anesthesia is technically unrelated, but people understandably conflate the two, especially now that ketamine is used in mental health contexts. Hence ketamine clinics speak of “the healing powers of dissociation”—seemingly the very thing of which you’d want to be healed.

There’s the crux of the issue: the k-hole. Ketamine gets you really, elaborately, bizarrely high. Doctors have never quite known how to describe this high or what to do about it. During the drug’s clinical trials in 1964, recovering patients reported that they’d been dead, suspended among the stars, or living in a movie. One researcher observed that ketamine “produced ‘zombies’ who were totally disconnected from their environment.” Investigators had to find the right word to broach these effects; hallucinations and zombies wouldn’t go over well with the FDA. An early contender, schizophrenomimetic (i.e., mimicking schizophrenia), was tossed out for obvious reasons. They settled on dissociative, which suggested a gossamer untethering of body and brain. A hot air balloon dissociates from the earth; the two halves of a Venn diagram are a dissociated circle. Confusingly, there was already a long history of dissociation in psychology, where the word describes someone too detached from reality to function. Dissociative anesthesia is technically unrelated, but people understandably conflate the two, especially now that ketamine is used in mental health contexts. Hence ketamine clinics speak of “the healing powers of dissociation”—seemingly the very thing of which you’d want to be healed.