Matthew Reisz at The Guardian:

While neuroscientists sometimes treat emotions as human universals, historians are keen to show how the words we use to describe our feelings, and indeed the feelings themselves, change with the times. “Nostalgia was one of the most studied medical conditions of the 19th century,” Arnold-Forster explains, believed to cause “palpitations and unexplained ruptures in the skin” as well as depression and disturbed sleep. It was first diagnosed among 17th-century Swiss mercenaries and referred to “a kind of pathological patriotic love, an intense and dangerous homesickness”. (Since sufferers were assumed to be missing the pure mountain air, one doctor suggested they should be put in tall towers to recuperate.) It was not until the early 20th century that homesickness and nostalgia in the current sense began to be seen as distinct.

Yet it continued to be treated as rather suspect. In the mid-20th century, a psychoanalyst called Nandor Fodor dismissed nostalgia, along with utopian politics and even the vogue for Tarzan films, as “the manifestation of a latent desire to return to the womb”.

more here.

In her spirited and richly detailed “Cunning Folk,” Tabitha Stanmore, a specialist in medieval and early modern magic, writes that between the 14th and 17th centuries, “a whole host of magical practitioners” pervaded villages, cities and royal courts — diviners, astrologers, charm makers, healers. Their customers were commoners and courtiers, peasants and merchants, housewives and queens.“This book is not about witches,” Stanmore emphasizes. The cunning folk were different, she explains, because they used “service magic,” not the dark arts, “to positively affect the world around them.” What’s more, “most people” marked a “distinction” between magicians of this kind (good, basically) and witches (evil), although the boundary, she admits, could be “fluid.” That’s because their clients’ requests could be “sinister,” to put it mildly. In 1613, for instance, the depraved Countess of Essex (later imprisoned for murdering a foe with a toxic enema) requested a slow-acting poison from a fortuneteller named Mary Woods, so she could bump off the Count. Woods skipped town rather than comply (so she told authorities) but was tried anyway; her fate is unknown.

In her spirited and richly detailed “Cunning Folk,” Tabitha Stanmore, a specialist in medieval and early modern magic, writes that between the 14th and 17th centuries, “a whole host of magical practitioners” pervaded villages, cities and royal courts — diviners, astrologers, charm makers, healers. Their customers were commoners and courtiers, peasants and merchants, housewives and queens.“This book is not about witches,” Stanmore emphasizes. The cunning folk were different, she explains, because they used “service magic,” not the dark arts, “to positively affect the world around them.” What’s more, “most people” marked a “distinction” between magicians of this kind (good, basically) and witches (evil), although the boundary, she admits, could be “fluid.” That’s because their clients’ requests could be “sinister,” to put it mildly. In 1613, for instance, the depraved Countess of Essex (later imprisoned for murdering a foe with a toxic enema) requested a slow-acting poison from a fortuneteller named Mary Woods, so she could bump off the Count. Woods skipped town rather than comply (so she told authorities) but was tried anyway; her fate is unknown.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration ( Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis took 41 years to make. It might take as long to understand. Coppola’s magnum opus, which premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival last night, is a movie of extraordinary highs and baffling lows, alternately dazzling and confounding. Sometimes, in the same moment, it’s both. When I asked colleagues who’d seen it—at a remote early-morning screening, added at the last minute to accommodate Coppola’s preference for IMAX—they looked at me like the mute humans in the

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis took 41 years to make. It might take as long to understand. Coppola’s magnum opus, which premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival last night, is a movie of extraordinary highs and baffling lows, alternately dazzling and confounding. Sometimes, in the same moment, it’s both. When I asked colleagues who’d seen it—at a remote early-morning screening, added at the last minute to accommodate Coppola’s preference for IMAX—they looked at me like the mute humans in the  A decade has passed, but exhuming Elliot Rodger’s life and ghastly final actions remains fraught. It risks inflicting further pain for the victims’ families and other survivors, and new revelations could feed the kind of infamy many perpetrators seek. The case stands out among the hundreds I’ve studied in 12 years of reporting on mass shootings. To this day it fuels copycat attackers who fixate on misogyny, making it an ongoing subject of news coverage and various academic and security research. It also helped catalyze policy change, in particular the spread of “red flag” laws aimed at keeping guns away from unstable people.

A decade has passed, but exhuming Elliot Rodger’s life and ghastly final actions remains fraught. It risks inflicting further pain for the victims’ families and other survivors, and new revelations could feed the kind of infamy many perpetrators seek. The case stands out among the hundreds I’ve studied in 12 years of reporting on mass shootings. To this day it fuels copycat attackers who fixate on misogyny, making it an ongoing subject of news coverage and various academic and security research. It also helped catalyze policy change, in particular the spread of “red flag” laws aimed at keeping guns away from unstable people. There is a buzz in India today – a sense of limitless possibilities. India has just

There is a buzz in India today – a sense of limitless possibilities. India has just  Now we may return briefly to the philosophy of Wittgenstein. If this seems a radical change of subject, an abrupt passage from the familiarity of comedy to the strangeness of technical philosophy, then it may be hoped that such an experience of difference may itself become important. Instead of connecting Keaton to Wittgenstein in some difficult conceptual fashion, I would be happy {great exact use of the word!} simply to convey the impression that in the same way as Keaton may be profound, Wittgenstein may be enjoyable. The relation between them could turn out to be something more interesting than the necessity to choose between comedy and philosophy.

Now we may return briefly to the philosophy of Wittgenstein. If this seems a radical change of subject, an abrupt passage from the familiarity of comedy to the strangeness of technical philosophy, then it may be hoped that such an experience of difference may itself become important. Instead of connecting Keaton to Wittgenstein in some difficult conceptual fashion, I would be happy {great exact use of the word!} simply to convey the impression that in the same way as Keaton may be profound, Wittgenstein may be enjoyable. The relation between them could turn out to be something more interesting than the necessity to choose between comedy and philosophy. A

A S

S Higher ed is at an impasse. So much about it sucks, and nothing about it is likely to change. Colleges and universities do not seem inclined to reform themselves, and if they were, they wouldn’t know how, and if they did, they couldn’t. Between bureaucratic inertia, faculty resistance, and the conflicting agendas of a heterogenous array of stakeholders, concerted change

Higher ed is at an impasse. So much about it sucks, and nothing about it is likely to change. Colleges and universities do not seem inclined to reform themselves, and if they were, they wouldn’t know how, and if they did, they couldn’t. Between bureaucratic inertia, faculty resistance, and the conflicting agendas of a heterogenous array of stakeholders, concerted change  Genetic information usually travels down a one-way street:

Genetic information usually travels down a one-way street:  Every generation of adults thinks the next is growing up in a broken world. “It is the story of humanity,” says Jonathan Haidt, author of a new book on a youth mental illness epidemic called

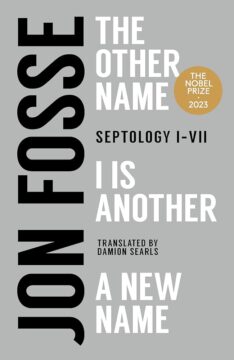

Every generation of adults thinks the next is growing up in a broken world. “It is the story of humanity,” says Jonathan Haidt, author of a new book on a youth mental illness epidemic called  Strangeness – estrangement – is very characteristic of this world – and a world it is, since all these prose works convey a very similar atmosphere and are largely set in the same locale – the Norwegian west coast, with its fjords, its islands, its fishing villages, the omnipresent sometimes threatening, sometimes comforting sea. (It’s rather piquant for an Irish reader to see the word ‘skerries’ coming up often in the English translation – it means of course reefs or rocky islands from Old Norse sker and is a reminder of our own Norse inheritance.)

Strangeness – estrangement – is very characteristic of this world – and a world it is, since all these prose works convey a very similar atmosphere and are largely set in the same locale – the Norwegian west coast, with its fjords, its islands, its fishing villages, the omnipresent sometimes threatening, sometimes comforting sea. (It’s rather piquant for an Irish reader to see the word ‘skerries’ coming up often in the English translation – it means of course reefs or rocky islands from Old Norse sker and is a reminder of our own Norse inheritance.)