Jennifer Couzin-Frankel in Science:

On a chilly holiday Monday in January 2020, a medical milestone passed largely unnoticed. In a New York City operating room, surgeons gently removed the heart from a 43-year-old man who had died and shuttled it steps away to a patient in desperate need of a new one.

On a chilly holiday Monday in January 2020, a medical milestone passed largely unnoticed. In a New York City operating room, surgeons gently removed the heart from a 43-year-old man who had died and shuttled it steps away to a patient in desperate need of a new one.

More than 3500 people in the United States receive a new heart each year. But this case was different—the first of its kind in the country. “It took us 6 months to prepare,” says Nader Moazami, surgical head of heart transplantation at New York University (NYU) Langone Health, where the operation took place. The run-up included oversight from an ethics board, education sessions with nurses and anesthesiologists, and lengthy conversations with the local organization that represents organ donor families. Physicians spent hours practicing in the hospital’s cadaver lab, prepping for organ recovery from the donor. “We wanted to make sure that we controlled every aspect,” Moazami says.

That’s because this donor, unlike most, was not declared dead because of loss of brain function. He had been suffering from end-stage liver disease and was comatose and on a ventilator, with no hope of regaining consciousness—but his brain still showed activity. His family made the wrenching choice to remove life support. Following that decision, they expressed a wish to donate his organs, even agreeing to transfer him to NYU Langone Health before he died so his heart could be recovered afterward.

More here.

W

W A spaceship lands near a small town in the Amazon, leaving the local government to manage an alien invasion. Dissidents who disappeared during a military dictatorship return years later as zombies. Bodies suddenly begin to fuse upon physical contact, forcing Colombians to navigate newly dangerous salsa bars and FARC guerrillas who have merged with tropical birds.

A spaceship lands near a small town in the Amazon, leaving the local government to manage an alien invasion. Dissidents who disappeared during a military dictatorship return years later as zombies. Bodies suddenly begin to fuse upon physical contact, forcing Colombians to navigate newly dangerous salsa bars and FARC guerrillas who have merged with tropical birds.

A common nutrient found in everyday foods might be the key to a long and healthy life, according to researchers from Columbia University. The nutrient in question is taurine, a naturally occurring amino acid with a range of essential roles around the body. Not only does the concentration of this nutrient in our bodies decrease as we age, but supplementation can increase lifespan by up to 12 percent in different species. Our main dietary sources of taurine are animal proteins, such as meat, fish and dairy, although it can also be found in some seaweeds and artificially supplemented energy drinks. It can also be produced inside the body from other amino acids. In a study published in the journal

A common nutrient found in everyday foods might be the key to a long and healthy life, according to researchers from Columbia University. The nutrient in question is taurine, a naturally occurring amino acid with a range of essential roles around the body. Not only does the concentration of this nutrient in our bodies decrease as we age, but supplementation can increase lifespan by up to 12 percent in different species. Our main dietary sources of taurine are animal proteins, such as meat, fish and dairy, although it can also be found in some seaweeds and artificially supplemented energy drinks. It can also be produced inside the body from other amino acids. In a study published in the journal  On November 4, 1963, the Beatles played at the Prince of Wales Theatre, in London, exuberant, exhausted, and defiant. “For our last number, I’d like to ask your help,” John Lennon cried out to the crowd. “Would the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands? And the rest of you, if you’d just rattle your jewelry.” Two weeks later, the band made their first appearance on American television, on NBC’s “Huntley-Brinkley Report.” “The hottest musical group in Great Britain today is the Beatles,” the reporter Edwin Newman said. “That’s not a collection of insects but a quartet of young men with pudding-bowl haircuts.” And, four days after that, “CBS Morning News with Mike Wallace” broadcast a four-minute report from “Beatleland,” by the London correspondent Alexander Kendrick. “The Beatles are said by sociologists to have a deeper meaning,” Kendrick reported. “Some say they are the authentic voice of the proletariat.” Everyone searched for that deeper meaning. The Beatles found it hard to take the search seriously.

On November 4, 1963, the Beatles played at the Prince of Wales Theatre, in London, exuberant, exhausted, and defiant. “For our last number, I’d like to ask your help,” John Lennon cried out to the crowd. “Would the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands? And the rest of you, if you’d just rattle your jewelry.” Two weeks later, the band made their first appearance on American television, on NBC’s “Huntley-Brinkley Report.” “The hottest musical group in Great Britain today is the Beatles,” the reporter Edwin Newman said. “That’s not a collection of insects but a quartet of young men with pudding-bowl haircuts.” And, four days after that, “CBS Morning News with Mike Wallace” broadcast a four-minute report from “Beatleland,” by the London correspondent Alexander Kendrick. “The Beatles are said by sociologists to have a deeper meaning,” Kendrick reported. “Some say they are the authentic voice of the proletariat.” Everyone searched for that deeper meaning. The Beatles found it hard to take the search seriously. [W]ith the victories of science, technology, and capitalism, we discovered that the cosmos of enchantment was unreal, or at best, utterly unverifiable; we cast most of the spirits into oblivion, and made room for their withered but venerable survivors in our chambers of private belief. Among the North Atlantic intelligentsia, at least, this story in some form is so widely hegemonic that even religious intellectuals accept it. For instance, in A Secular Age (2007), Charles Taylor—a practicing Catholic—affirms, albeit in his own peculiar way, the consensus of “disenchantment.” In the pre-modern epoch of enchantment, Taylor explains, the boundary that separated our world from the sacred was porous and indistinct; traffic between the two spheres was frequent, if not always desired or friendly. “Disenchantment” began with the church’s rationalization of doctrine and the growing awareness that Christianity was not the world’s only religion. Now, having left the enchanted universe behind, we disenchanted dwell within the moral and ontological parameters of an “immanent frame”: the world as apprehended through reason and science, bereft of immaterial and unquantifiable forces, structured by the immutable laws of nature and the contingent traditions of human societies.

[W]ith the victories of science, technology, and capitalism, we discovered that the cosmos of enchantment was unreal, or at best, utterly unverifiable; we cast most of the spirits into oblivion, and made room for their withered but venerable survivors in our chambers of private belief. Among the North Atlantic intelligentsia, at least, this story in some form is so widely hegemonic that even religious intellectuals accept it. For instance, in A Secular Age (2007), Charles Taylor—a practicing Catholic—affirms, albeit in his own peculiar way, the consensus of “disenchantment.” In the pre-modern epoch of enchantment, Taylor explains, the boundary that separated our world from the sacred was porous and indistinct; traffic between the two spheres was frequent, if not always desired or friendly. “Disenchantment” began with the church’s rationalization of doctrine and the growing awareness that Christianity was not the world’s only religion. Now, having left the enchanted universe behind, we disenchanted dwell within the moral and ontological parameters of an “immanent frame”: the world as apprehended through reason and science, bereft of immaterial and unquantifiable forces, structured by the immutable laws of nature and the contingent traditions of human societies. Borges famously singles out for praise Menard’s description of “truth’ whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past …” (CF, 94). A rejected draft might have said something like this: “truth, whose father is history,” “preserver of time ….” Then “father” and “preserver” crossed out and replaced with “mother” and “rival,” the point of the revision being to express Menard’s thought better and also to make sure the text in which he expressed it coincided (“word for word and line for line”) with what Cervantes had written. Of course, it’s hardly likely that in expressing his own thoughts he would find himself doing so in Cervantes’s words, but that’s the problem that infinite time (like the monkeys and the typewriters or being “immortal” [CF, 91]) is supposed to solve. However, the idea that he could, in revising, check to see how he was doing is a deeper problem. You wouldn’t know that truth whose father is history was wrong unless you checked, but if you checked and then corrected, you’d be copying. So, you could never check. But if you didn’t know what the original said, how could you understand yourself to be trying to reproduce it? The difficulty of Menard’s project, in other words, is not exactly how hard it is to succeed in producing even a few sentences that coincide with rather than copy Cervantes but how hard it is even to try, how hard it is even to know what trying is.

Borges famously singles out for praise Menard’s description of “truth’ whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past …” (CF, 94). A rejected draft might have said something like this: “truth, whose father is history,” “preserver of time ….” Then “father” and “preserver” crossed out and replaced with “mother” and “rival,” the point of the revision being to express Menard’s thought better and also to make sure the text in which he expressed it coincided (“word for word and line for line”) with what Cervantes had written. Of course, it’s hardly likely that in expressing his own thoughts he would find himself doing so in Cervantes’s words, but that’s the problem that infinite time (like the monkeys and the typewriters or being “immortal” [CF, 91]) is supposed to solve. However, the idea that he could, in revising, check to see how he was doing is a deeper problem. You wouldn’t know that truth whose father is history was wrong unless you checked, but if you checked and then corrected, you’d be copying. So, you could never check. But if you didn’t know what the original said, how could you understand yourself to be trying to reproduce it? The difficulty of Menard’s project, in other words, is not exactly how hard it is to succeed in producing even a few sentences that coincide with rather than copy Cervantes but how hard it is even to try, how hard it is even to know what trying is. In 1923, the year after James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was first published in its complete form, T. S. Eliot wrote: “I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” Although Ulysses was not yet widely available at the time—its initial print runs were minuscule and it would be banned repeatedly by censorship boards—Eliot was writing in defense of a novel already broadly disparaged as immoral, obscene, formless, and chaotic. His friend Virginia Woolf had described it in her diary as “an illiterate, underbred book … the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are.” In comparison, Eliot’s praise is triumphal. “A book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” And yet this proposed relationship between Ulysses and its readers may not seem altogether inviting either. Do we really want to read a novel in order to experience the sensation of inescapable debt? In the century since its publication, Ulysses has of course become a monument not only of modernist literature but of the novel itself. But it’s also a notoriously “difficult” book. Among all English-language novels, there may be no greater gulf between how much a work is celebrated and discussed, and how seldom it is actually read.

In 1923, the year after James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was first published in its complete form, T. S. Eliot wrote: “I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” Although Ulysses was not yet widely available at the time—its initial print runs were minuscule and it would be banned repeatedly by censorship boards—Eliot was writing in defense of a novel already broadly disparaged as immoral, obscene, formless, and chaotic. His friend Virginia Woolf had described it in her diary as “an illiterate, underbred book … the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are.” In comparison, Eliot’s praise is triumphal. “A book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” And yet this proposed relationship between Ulysses and its readers may not seem altogether inviting either. Do we really want to read a novel in order to experience the sensation of inescapable debt? In the century since its publication, Ulysses has of course become a monument not only of modernist literature but of the novel itself. But it’s also a notoriously “difficult” book. Among all English-language novels, there may be no greater gulf between how much a work is celebrated and discussed, and how seldom it is actually read. We now have a good explanation for how our brain keeps track of a conversation while we are in a loud, crowded room, a discovery that could improve hearing aids.

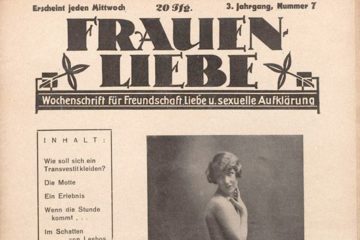

We now have a good explanation for how our brain keeps track of a conversation while we are in a loud, crowded room, a discovery that could improve hearing aids. Berlin in the 1920s was ablaze with sexual and gender freedom. Magazines at newsstands boasted covers featuring people who were transgender and clad scantily. Their headlines touted stories on “Homosexual Women and the Upcoming Legislative Elections,” and offered, on occasion, homoerotic fiction inside its pages.

Berlin in the 1920s was ablaze with sexual and gender freedom. Magazines at newsstands boasted covers featuring people who were transgender and clad scantily. Their headlines touted stories on “Homosexual Women and the Upcoming Legislative Elections,” and offered, on occasion, homoerotic fiction inside its pages.