Category: Archives

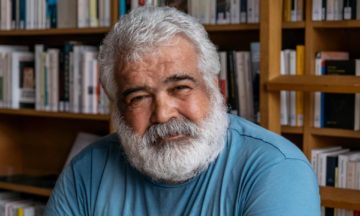

Khaled Khalifa: ‘All the places of my childhood are destroyed’

Michael Safi in The Guardian:

Khaled Khalifa is a Syrian novelist, poet and screenwriter whose work has been awarded the Naguib Mahfouz medal for literature, one of the Arab world’s highest literary honours. His soulful, often wry stories traverse time but are centred on the Syrian city of Aleppo, near where Khalifa was born in 1964, and once one of the world’s great cultural and trading hubs.

Khaled Khalifa is a Syrian novelist, poet and screenwriter whose work has been awarded the Naguib Mahfouz medal for literature, one of the Arab world’s highest literary honours. His soulful, often wry stories traverse time but are centred on the Syrian city of Aleppo, near where Khalifa was born in 1964, and once one of the world’s great cultural and trading hubs.

He studied and spent his early career in the city, but has lived in Damascus since 1999, one of the few writers who stayed throughout the country’s appalling civil war. He has tried to write about the Syrian capital, he said, but keeps finding himself drawn back to his home city. “After 50 pages, I felt it was not good writing,” he said. “I don’t know the fragrance of Damascus. So I turned back to Aleppo, and I accepted: OK, this is my place. I’ll write all my books about Aleppo. She is my city and resides deep in myself, in my soul.”

While Khalifa was writing his new book, No One Prayed Over Their Graves, Aleppo was comprehensively destroyed in fighting between the Syrian government and rebels. His work is banned in Syria.

More here.

Mughal-e-Azam: The Musical’s Prelude Screening At Times Square

People on Drugs Like Ozempic Say Their ‘Food Noise’ Has Disappeared

Dani Blum in The New York Times:

Until she started taking the weight loss drug Wegovy, Staci Klemmer’s days revolved around food. When she woke up, she plotted out what she would eat; as soon as she had lunch, she thought about dinner. After leaving work as a high school teacher in Bucks County, Pa., she would often drive to Taco Bell or McDonald’s to quell what she called a “24/7 chatter” in the back of her mind. Even when she was full, she wanted to eat. Almost immediately after Ms. Klemmer’s first dose of medication in February, she was hit with side effects: acid reflux, constipation, queasiness, fatigue. But, she said, it was like a switch flipped in her brain — the “food noise” went silent.

Until she started taking the weight loss drug Wegovy, Staci Klemmer’s days revolved around food. When she woke up, she plotted out what she would eat; as soon as she had lunch, she thought about dinner. After leaving work as a high school teacher in Bucks County, Pa., she would often drive to Taco Bell or McDonald’s to quell what she called a “24/7 chatter” in the back of her mind. Even when she was full, she wanted to eat. Almost immediately after Ms. Klemmer’s first dose of medication in February, she was hit with side effects: acid reflux, constipation, queasiness, fatigue. But, she said, it was like a switch flipped in her brain — the “food noise” went silent.

“I don’t think about tacos all the time anymore,” Ms. Klemmer, 57, said. “I don’t have cravings anymore. At all. It’s the weirdest thing.” Dr. Andrew Kraftson, a clinical associate professor at Michigan Medicine, said that over his 13 years as an obesity medicine specialist, people he treated would often say they couldn’t stop thinking about food. So when he started prescribing Wegovy and Ozempic, a diabetes medication that contains the same compound, and patients began to use the term food noise, saying it had disappeared, he knew exactly what they meant.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Reeling in a Skate on Kachemak Bay, Alaska

We drop bait and jig down eighteen fathoms,

trolling bottom for the halibut they say

are white and big as jib sails full of wind.

We drift this way all morning and I watch the men

pull up 30-pounders and sometimes

scaly Irish Lords, lustered as fool’s gold.

Drugged by the surprising warmth of this

eclipsed and argent Arctic light, I am amazed

when my line drags taut and in my hands

the heavy rod dips like a heron bends to drink.

I reel and reel, pulling up my own weight,

heavy as wet canvas. The men say to go slowly,

it will roll in fear and dive from foreign sun—

this fish has never seen the light. But who knows

what I’ve snagged from sodden sleep,

what blunt-eyed creature I haul out of darkness,

a ghostly harbinger that wavers toward me

like an insubstantial scrap of paper,

becoming larger as it nears. Too tired to resist

the last few feet it seems to help,

ascending easily, entranced by this bright world.

by Susan Elbe

—from Rattle #16, Winter 2001

Sunday, July 2, 2023

‘Why I might have done what I did’: conversations with Ireland’s most notorious murderer

Mark O’Connell in The Guardian:

Among Irish people old enough to remember the summer of 1982, Malcolm Macarthur is as close to a household name as it is possible for a murderer to be. He grew up in County Meath in the east of Ireland, on a grand estate with a housekeeper, a gardener and a governess. In his 20s, he received a large inheritance, and lived well on its bounty. But on the brink of middle age, he found he was going broke. At the time, the IRA was conducting a campaign of bank heists to fund their struggle. Macarthur was a clever and capable man, he reasoned, and so why should he not be able to pull off something along those lines?

Among Irish people old enough to remember the summer of 1982, Malcolm Macarthur is as close to a household name as it is possible for a murderer to be. He grew up in County Meath in the east of Ireland, on a grand estate with a housekeeper, a gardener and a governess. In his 20s, he received a large inheritance, and lived well on its bounty. But on the brink of middle age, he found he was going broke. At the time, the IRA was conducting a campaign of bank heists to fund their struggle. Macarthur was a clever and capable man, he reasoned, and so why should he not be able to pull off something along those lines?

He had been living for some months with a woman named Brenda Little and their son in Tenerife. He told Little that he had financial affairs to attend to, and flew to Dublin.

More here.

Most of the energy you put into a gasoline car is wasted; this is not the case for electric cars

Hannah Ritchie in Sustainability by Numbers:

For every dollar of petrol you put, you get just 20 cents’ worth of driving motion. The other 80 cents is wasted along the way – most of it as heat from the engine.

For every dollar of petrol you put, you get just 20 cents’ worth of driving motion. The other 80 cents is wasted along the way – most of it as heat from the engine.

Electric cars are much better at converting energy into motion. For every dollar of electricity you put in, you get 67 cents of driving motion plus another 22 cents of energy that’s recovered from regenerative braking. That means you get 89 cents’ worth out.

More here.

Two Ancestral Languages

Richard Dawkins at The Poetry of Reality:

The collective power endowed by language is captured in the legend of the Tower of Babel, where it threatened even God himself. “Go to,” God said, “Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” And lo, as a result of quasi-evolutionary divergence, we speak many thousands of mutually unintelligible tongues, the exact number undefined, mostly because dialect grades into language so we can’t decide where one language ends and the next begins. This smearing out is seen both across geographical space (think English worldwide) and through historical time as languages evolve through the centuries (try reading Chaucer). Nevertheless, because language is partly digital, chunked into the discrete semantic units that we call words, it is capable of great fidelity of transmission, especially in written forms. Yet, despite being thus capable, precious little verbal information from our dead ancestors filters down.

The collective power endowed by language is captured in the legend of the Tower of Babel, where it threatened even God himself. “Go to,” God said, “Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” And lo, as a result of quasi-evolutionary divergence, we speak many thousands of mutually unintelligible tongues, the exact number undefined, mostly because dialect grades into language so we can’t decide where one language ends and the next begins. This smearing out is seen both across geographical space (think English worldwide) and through historical time as languages evolve through the centuries (try reading Chaucer). Nevertheless, because language is partly digital, chunked into the discrete semantic units that we call words, it is capable of great fidelity of transmission, especially in written forms. Yet, despite being thus capable, precious little verbal information from our dead ancestors filters down.

But there is another language, also digital, of far greater precision and fidelity of transmission, which does preserve ancestral information, not through a paltry few generations but through hundreds of millions; a parallel language, which is not a human monopoly but is shared by all life: all animals, fungi, plants, bacteria, and archaea; a truly universal language that doesn’t suffer the confusion of dialect drift or trans-generational decay. Nor does it fall victim to the cumulative inflation of my opening fantasy, because it does not grow with each generation. As every schoolchild knows, acquired characteristics are not inherited. The genetic database changes, not cumulatively but by subtraction and addition approximately keeping pace with each other.

More here.

Burn Down the Admissions System

Yascha Mounk in Persuasion:

A few years ago, I listened to Jim Yong Kim, then the President of the World Bank, address the Milken Global Conference, a gathering that is about as plutocratic as it sounds. At the start of his remarks, Kim told the multimillionaires and billionaires who made up the bulk of the audience an anecdote, which he seemed to consider charming, about how he got his job.

A few years ago, I listened to Jim Yong Kim, then the President of the World Bank, address the Milken Global Conference, a gathering that is about as plutocratic as it sounds. At the start of his remarks, Kim told the multimillionaires and billionaires who made up the bulk of the audience an anecdote, which he seemed to consider charming, about how he got his job.

One day, while Kim was still in his previous job as the President of Dartmouth College, his assistant informed him of an unexpected phone call from Tim Geithner, the Secretary of the Treasury. Kim immediately reached for a pen. Naturally, he said, he expected that Geithner would ask for some nephew or family friend of his to get special consideration in the admissions process, and Kim wanted to be ready to jot down the applicant’s name. But to his astonishment, that wasn’t the case: Geithner was actually calling to see whether he might be interested in running the World Bank! (Cue appreciative chuckles from the audience.)

What was remarkable about this anecdote is just how normalized these forms of influence-peddling are in America’s elite.

More here.

The Medley Song

Sunday Poem

Introduction to Poetry

I ask them to take a poem

and hold it up to the light

like a color slide

or press an ear against its hive.

I say drop a mouse into a poem

and watch him probe his way out,

or walk inside the poem’s room

and feel the walls for a light switch.

I want them to waterski

across the surface of a poem

waving at the author’s name on the shore.

But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

by Billy Collins

from The Apple That Astonished Paris

Robert Black (1956 – 2023) Double Bassist

Julian Sands (1958 – 2023) Actor

Bobby Osborne (1931 – 2023) Bluegrass Musician

Saturday, July 1, 2023

Congress Redux?

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

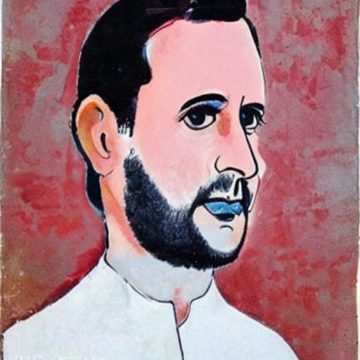

On 7 September last year, the senior Congress leader Rahul Gandhi launched Bharat Jodo Yatra, a protest march to ‘unite India’ against the ‘divisive politics’ of the BJP-led government. Stretching from Kanyakumari, on the southern tip of India, to Jammu and Kashmir in the north, the yatra covered some 3,500 kilometers and twelve states. A number of celebrities made headlines by joining this five-month journey. As did Gandhi’s outfit (a single polo T-shirt throughout the winter), his scraggly beard and his fitness regime (‘fourteen pushups in ten seconds’). The right-wing backlash was predictable: some mocked Gandhi’s Burberry wardrobe, others likened his facial hair to Saddam Hussein’s. Yet, in every state he crossed, the 52-year-old scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty saw his approval ratings increase – most of all in Delhi, where they jumped from 32% to 55%. Riding a wave of mass popularity for the first time in his career, Gandhi provided this memorable summation: ‘In the bazaar of hate, I am opening shops of love’. And then, within a few weeks, his star plummeted. On 23 March, a lower Indian court convicted him of making defamatory comments about the surname of the Prime Minister. A day later, he was summarily ejected from parliament.

While Gandhi’s political future is in jeopardy, his nemesis still appears to be untouchable, despite the volatility of his period in office. Over nine years, Narendra Modi has unleashed a devastating series of ‘shock and awe’ operations which have consistently failed to dent his popularity. In November 2016, he withdrew 86% of the circulating currency overnight, costing 10-12 million workers their jobs.

More here.

The myth of mirrored twins

Gavin Evansi in Aeon:

Gavin Evansi in Aeon:

Thirteen days before the start of the Second World War, a 35-year-old unmarried immigrant woman gave birth slightly prematurely to identical twins at the Memorial Hospital in Piqua, Ohio and immediately put them up for adoption. The boys spent their first month together in a children’s home before Ernest and Sarah Springer adopted one – and would have adopted both had they not been told, incorrectly, that the other twin had died. Two weeks later, Jess and Lucille Lewis adopted the other baby and, when they signed the papers at the local courthouse, calling their boy James, the clerk remarked: ‘That’s what [the Springers] named their son.’ Until then they hadn’t known he was a twin.

The boys grew up 40 miles apart in middle-class Ohioan families. Although James Lewis was six when he learnt he’d been adopted, it was only in his late 30s that he began searching for his birth family at the Ohio courthouse. In 1979, the adoption agency wrote to James Springer, who was astonished by the news, because as a teenager he’d been told his twin had died at birth. He phoned Lewis and four days later they met – a nervous handshake and then beaming smiles. Reports on their case prompted a Minneapolis-based psychologist, Thomas Bouchard, to contact them, and a series of interviews and tests began. The Jim Twins, as they were known, became Bouchard’s star turn.

Both Jims, it transpired, had worked as deputy sheriffs, and had done stints at McDonald’s and at petrol stations; they’d both taken holidays at Pass-a-Grille beach in Florida, driving there in their light-blue Chevrolets. Each had dogs called Toy and brothers called Larry, and they’d married and divorced women called Linda, then married Bettys. They’d called their first sons James Alan/Allan. Both were good at maths and bad at spelling, loved carpentry, chewed their nails, chain-smoked Salem and drank Miller Lite beer. Both had haemorrhoids, started experiencing migraines at 18, gained 10 lb in their early 30s, and had similar heart problems and sleep patterns.

More here.

The Localist

Jonathan Levy in Boston Review:

Jonathan Levy in Boston Review:

One puzzle in the intellectual history of the twentieth century is why the University of Chicago became the leading bastion of free market economics.

Scholars have proposed compelling explanations, from the strong rooting of “price theory” at Chicago by the end of the 1930s to the participation of many of its faculty members in postwar, pro-market advocacy groups that began to embrace neoliberalism by the 1960s. But having spent most of my adult life at the university and in its surrounding neighborhood of Hyde Park, I can’t help but wonder about a more quotidian contributing factor: the area’s limited range of commerce in the days when Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, and George Stigler walked these streets.

Hyde Park is on Chicago’s South Side, not the posh North. The area once buzzed with urban commercial traffic—right after World War II, when many Black people moved to the city from the South in order to work in factories. Famous jazz and blues clubs abounded on the neighborhood’s central commercial corridor of 55th street, where legends like Coleman Hawkins, Art Blakey, Thelonious Monk, and Sonny Rollins played. But then the factories began to shutdown. Poverty and street crime rose. The U.S. “urban crisis” fell on Chicago.

At the university, fears arose about white flight and a potential diminished ability to recruit students and faculty. Thus began a decades-long “urban renewal” project in Hyde Park, carried out by the city and the university.

More here.

On marriage, Netflix and other things I hate

Devorah Baum in The White Review:

1. ‘It’s kind of crazy to shop at Target, watch Netflix, drive a Honda, and still have a husband.’

1. ‘It’s kind of crazy to shop at Target, watch Netflix, drive a Honda, and still have a husband.’

Marriage falls into a specific category of things I don’t want to think about because their meaning swells the more you do. Personally, socially, historically. And yet, I am always interested in love stories: I listen to my friends talk about their love lives and when they apologise for dwelling on something – ‘is this boring?!’ – I answer, ‘love is the subject.’ I am interested in how we organise our lives by connection with other people, in how we live alongside others, in how love is a social construct and a form of relation. Love is the subject, by which I mean, love is something we want to narrate and discuss, because words make this inexplicable and incomprehensible thing – other people – feel less ambiguous, perhaps closer to certainty.

I don’t mean to conflate marriage and love. Quite the opposite – it is marriage’s function as an organising logic that I fear, that I believe does not work for anyone (especially not women). When I speak of marriage, it is not love I think of, but power. I think about Phyllis Rose discussing this in the introduction to PARALLEL LIVES: FIVE VICTORIAN MARRIAGES (1983): ‘When we resign power or assume new power, we insist it is not happening and demand to be talked to about love. Perhaps that is what love is – the momentary or prolonged refusal to think of another person in terms of power.’ But power is impossible to sidestep. A page later: ‘Who can resist the thought that love is the ideological bone thrown to women to distract their attention from the powerlessness of their lives?’

More here.

Post-Anthropocene Humanism

Nathan Gardels at Noema:

The controversies of late over the perils and promise of generative AI have raised anew the philosophical question of where technological sovereignty ends and human autonomy begins. Will the super-intelligent capacities of the putative servant we have invented end up being our actual master?

The controversies of late over the perils and promise of generative AI have raised anew the philosophical question of where technological sovereignty ends and human autonomy begins. Will the super-intelligent capacities of the putative servant we have invented end up being our actual master?

“The fact is that the powers which seem to use and govern technology are in reality more or less unwittingly used and governed by it,” Giorgio Agamben, the philosopher of biopolitics, observed in his presentation to the opening symposium of the Berggruen Institute Europe in Venice. “Both totalitarian and democratic regimes share the same incapability to govern technology, and both end up transforming themselves through the technologies they believed they were using for their own purposes. Why does it seem so hard and even impossible to govern technology?” he asked.

more here.

What We Get Wrong About Drugs Like Ozempic

Yoni Freedhoff in Time:

Imagine a new medication was developed that not only provided meaningful improvement for the debilitating chronic condition it’s prescribed, but also helps to treat and prevent a myriad of other serious diseases. Imagine this same drug markedly improved a person’s quality of life with noted reductions in pain and improvements in mobility along with increases in confidence and mood. Now imagine that the media and medical coverage of its release are almost uniformly negative or sensationalistic.

Imagine a new medication was developed that not only provided meaningful improvement for the debilitating chronic condition it’s prescribed, but also helps to treat and prevent a myriad of other serious diseases. Imagine this same drug markedly improved a person’s quality of life with noted reductions in pain and improvements in mobility along with increases in confidence and mood. Now imagine that the media and medical coverage of its release are almost uniformly negative or sensationalistic.

This is precisely what has happened with the new generation of anti-obesity medications, that began with Wegovy/Ozempic and with many more rapidly on their way. Currently approved medications lead people with obesity to lose on average 15% of their body weight which in turn has dramatic benefits for multiple weight responsive medical conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, GERD, fatty liver disease, and more. Clinical trials of newer molecules demonstrate even greater losses with the most recent, for Retatrutide, demonstrating a 24% body weight loss after 48 weeks of use and where weight in those participants appeared to still be dropping. Sustained weight loss has been shown to decrease the risk of developing those same conditions as well as some of our most common cancers including breast, uterine, and colon.

More here.