anyone lived in a pretty how town

(with up so floating many bells down)

spring summer autumn winter

he sang his didn’t he danced his did

Women and men (both little and small)

cared for anyone not at all

they sowed their isn’t they reaped their same

sun moon stars rain

children guessed (but only a few

and down they forgot as up they grew

autumn winter spring summer)

that noone loved him more by more

when by now and tree by leaf

she laughed his joy she cried his grief

bird by snow and stir by still

anyone’s any was all to her

someones married their everyones

laughed their cryings and did their dance

(sleep wake hope and then) they

said their nevers and slept their dream

stars rain sun moon

(and only the snow can begin to explain

how children are apt to forget to remember

with up so floating many bells down)

one day anyone died i guess

(and noone stooped to kiss his face)

busy folk buried them side by side

little by little and was by was

all by all and deep by deep

and more by more they dream their sleep

noone and anyone earth by april

wish by spirit and if by yes.

Women and men (both dong and ding)

summer autumn winter spring

reaped their sowing and went their came

sun moon stars rain

by e.e.cummings

from 50 poems

Hawthorne Books, 1940

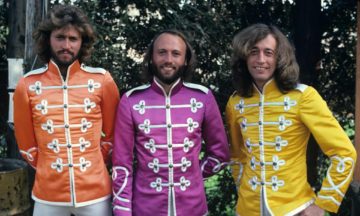

This book contains few new interviews about the “insanely productive” group who sold more than 220m records: it is author-led, meaning we are mainly given Bob Stanley’s opinions about the

This book contains few new interviews about the “insanely productive” group who sold more than 220m records: it is author-led, meaning we are mainly given Bob Stanley’s opinions about the  Almost a century ago, physics produced a problem child, astonishingly successful yet profoundly puzzling. Now, just in time for its 100th birthday, we think we’ve found a simple diagnosis of its central eccentricity.

Almost a century ago, physics produced a problem child, astonishingly successful yet profoundly puzzling. Now, just in time for its 100th birthday, we think we’ve found a simple diagnosis of its central eccentricity. A lot of people — at least, a lot of people who read this blog — know of Matt Yglesias’ book

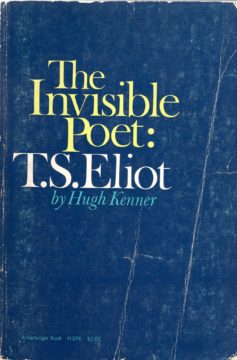

A lot of people — at least, a lot of people who read this blog — know of Matt Yglesias’ book  According to Kenner, the Hollow Men provides the first expression of the “structural principle” of Eliot’s later work and, I would suggest, of Kenner’s work as well. What is that principle? Eliot’s aim is to articulate “moral states which to an external observer are indistinguishable from one another” (IP, 163). So that we can “judge a man’s action,” Kenner says, but “we cannot judge the man by his actions.” What Kenner calls “distinct actions,” occlude from the observer the nature of a man’s true actions. And since what we are asked to judge are “moral states,” it naturally follows that we are not meant to judge works of art, which is exactly what Kenner says (IP, 163). “In art,” Kenner writes, “actions are determined by their objects.” In morals, by contrast, actions are “determined by their motives, which are hidden: hidden, often, from the actor” (IP, 163). The art that Kenner admires is anti-art in the sense that conventional artworks are construed as the expression of distinct actions, a kind of action we sometimes define as intentional tout court.

According to Kenner, the Hollow Men provides the first expression of the “structural principle” of Eliot’s later work and, I would suggest, of Kenner’s work as well. What is that principle? Eliot’s aim is to articulate “moral states which to an external observer are indistinguishable from one another” (IP, 163). So that we can “judge a man’s action,” Kenner says, but “we cannot judge the man by his actions.” What Kenner calls “distinct actions,” occlude from the observer the nature of a man’s true actions. And since what we are asked to judge are “moral states,” it naturally follows that we are not meant to judge works of art, which is exactly what Kenner says (IP, 163). “In art,” Kenner writes, “actions are determined by their objects.” In morals, by contrast, actions are “determined by their motives, which are hidden: hidden, often, from the actor” (IP, 163). The art that Kenner admires is anti-art in the sense that conventional artworks are construed as the expression of distinct actions, a kind of action we sometimes define as intentional tout court. T

T For millennia, the movements of the celestial bodies in the heavens above, from shining planets to the faintest of stars, have provided practical guidance to navigators and spiritual direction to oracles. But some signals created by the stars are invisible to the naked human eye.

For millennia, the movements of the celestial bodies in the heavens above, from shining planets to the faintest of stars, have provided practical guidance to navigators and spiritual direction to oracles. But some signals created by the stars are invisible to the naked human eye. On 9 October 1911, Franz Kafka, then 28 years old, wrote in his diary that he didn’t expect to reach the age of 40. At the time of this entry, he was not yet stricken with the tuberculosis that would lead to his death in 1924, shortly before his

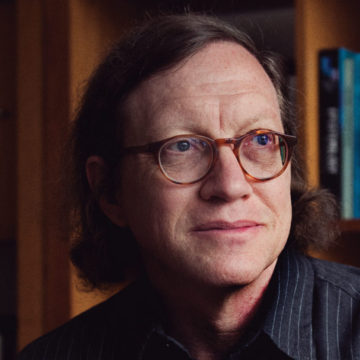

On 9 October 1911, Franz Kafka, then 28 years old, wrote in his diary that he didn’t expect to reach the age of 40. At the time of this entry, he was not yet stricken with the tuberculosis that would lead to his death in 1924, shortly before his  Last year’s Nobel Prize for experimental tests of Bell’s Theorem was the first Nobel in the foundations of quantum mechanics since Max Born in 1954. Quantum foundations is enjoying a bit of a resurgence, inspired in part by improving quantum technology but also by a realization that understanding quantum mechanics might help with other problems in physics (and be important in its own right). Tim Maudlin is a leading philosopher of physics and also a skeptic of the Everett interpretation. We discuss the logic behind hidden-variable approaches such as Bohmian mechanics, and also the broader question of the importance of the foundations of physics.

Last year’s Nobel Prize for experimental tests of Bell’s Theorem was the first Nobel in the foundations of quantum mechanics since Max Born in 1954. Quantum foundations is enjoying a bit of a resurgence, inspired in part by improving quantum technology but also by a realization that understanding quantum mechanics might help with other problems in physics (and be important in its own right). Tim Maudlin is a leading philosopher of physics and also a skeptic of the Everett interpretation. We discuss the logic behind hidden-variable approaches such as Bohmian mechanics, and also the broader question of the importance of the foundations of physics. It’d be a mistake to characterize the risk of human extinction from artificial intelligence as a “fringe” concern now hitting the mainstream, or a decoy to distract from current harms caused by AI systems. Alan Turing, one of the fathers of modern computing, famously wrote in 1951 that “once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers. … At some stage therefore we should have to expect the machines to take control.” His colleague I. J. Good agreed; more recently, so did Stephen Hawking. When today’s luminaries warn of “extinction risk” from artificial intelligence, they are in good company, restating a worry that has been around as long as computers. These concerns predate the founding of any of the current labs building frontier AI, and the historical trajectory of these concerns is important to making sense of our present-day situation. To the extent that frontier labs do focus on safety, it is in large part due to advocacy by researchers who do not hold any financial stake in AI. Indeed, some of them would prefer AI didn’t exist at all.

It’d be a mistake to characterize the risk of human extinction from artificial intelligence as a “fringe” concern now hitting the mainstream, or a decoy to distract from current harms caused by AI systems. Alan Turing, one of the fathers of modern computing, famously wrote in 1951 that “once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers. … At some stage therefore we should have to expect the machines to take control.” His colleague I. J. Good agreed; more recently, so did Stephen Hawking. When today’s luminaries warn of “extinction risk” from artificial intelligence, they are in good company, restating a worry that has been around as long as computers. These concerns predate the founding of any of the current labs building frontier AI, and the historical trajectory of these concerns is important to making sense of our present-day situation. To the extent that frontier labs do focus on safety, it is in large part due to advocacy by researchers who do not hold any financial stake in AI. Indeed, some of them would prefer AI didn’t exist at all. Gravitational waves are back, and they’re bigger than ever.

Gravitational waves are back, and they’re bigger than ever. The internet was created by the U.S. military as a way to preserve communications to missile silos in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack:

The internet was created by the U.S. military as a way to preserve communications to missile silos in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack: 350 pages into Vikram Chandra’s epic novel Red Earth and Pouring Rain, a particular story within a story within a story caught my attention the first time I read it in the mid-aughts. Perhaps one day I’ll pen a lecture on the image of printers within contemporary literature. This one involves the wily Calcutta printer Sorkar, working on commission to an aloof Englishman named Markline. Sorkar wanders his shopfloor, occasionally handing out special letters to his Bengali typesetters to substitute for their fonts. What do these letters spell? It turns out that they are a cipher, a means of encoding secret linguistic jabs against the printer’s British master. They range from political statements such as “The Company makes widows and famines, and calls it peace” to the simple and effective, “Fuck you.”

350 pages into Vikram Chandra’s epic novel Red Earth and Pouring Rain, a particular story within a story within a story caught my attention the first time I read it in the mid-aughts. Perhaps one day I’ll pen a lecture on the image of printers within contemporary literature. This one involves the wily Calcutta printer Sorkar, working on commission to an aloof Englishman named Markline. Sorkar wanders his shopfloor, occasionally handing out special letters to his Bengali typesetters to substitute for their fonts. What do these letters spell? It turns out that they are a cipher, a means of encoding secret linguistic jabs against the printer’s British master. They range from political statements such as “The Company makes widows and famines, and calls it peace” to the simple and effective, “Fuck you.”