Category: Archives

Noam Chomsky on Language, Left Libertarianism, and Progress

Tyler Cowen at Conversations with Tyler:

COWEN: If I think of your thought, and I compare it to the thought of Wilhelm von Humboldt, what’s the common ontological element in both of your thoughts that leads you to more or less agree on both language and liberty?

CHOMSKY: Von Humboldt was, first of all, a great linguist who recognized some fundamental principles of language which were rare at the time and are only beginning to be understood. But in the social and political domain, he was not only the founder of the modern research university, but also one of the founders of classical liberalism.

CHOMSKY: Von Humboldt was, first of all, a great linguist who recognized some fundamental principles of language which were rare at the time and are only beginning to be understood. But in the social and political domain, he was not only the founder of the modern research university, but also one of the founders of classical liberalism.

His fundamental principle — as he said, it’s actually an epigram for John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty — is that the fundamental right of every person is to be free from external illegitimate constraints, free to inquire, to create, to pursue their own interests and concerns without arbitrary authority of any sort restricting or limiting them.

COWEN: Now, you’ve argued that Humboldt was a Platonist of some kind, that he viewed learning as some notion of reminiscence. Are you, in the same regard, also a Platonist?

CHOMSKY: Leibniz pointed out that Plato’s theory of reminiscence was basically correct, but it had to be purged of the error of reminiscence — in other words, not an earlier life, but rather something intrinsic to our nature. Leibniz couldn’t have proceeded as we can today, but now we would say something that has evolved and has become intrinsic to our nature. For people like Humboldt, what was crucial to our nature was what is sometimes called the instinct for freedom. Basic, fundamental human property should lie at the basis of our social and economic reasoning.

It’s also the critical property of human language and thought, as was recognized in the early Scientific Revolution — Galileo, Leibniz — a little later, people like Humboldt in the Romantic era.

More here.

This Is A Celebration Of Artistic Integrity

David Hockney, Richard Feynman, A Pair Of Twins And Some Bugs

Lawrence Weschler at Wondercabinet:

So I woke up this morning and over there to the side of my bedroom was the poster with that David Hockney painting I’ve always loved though perhaps, it occurred to me, never really looked at before—you know how it can get to be with the things one surrounds oneself with everyday. As you can see, it’s one of his pool paintings (this one dated 1971), which as a group played all sorts of changes on themes of surface and transparency and presence and awareness and memory (the wet paint on canvas, drying, summoning forth what it is like to call back up the fading memory of what it was like to soak in the water that balmy distant afternoon, one’s shoulders pressed against the poolside rim, gazing out, observing the dance of light on the surface of the water, and through that surface to the depths beneath, the way that gaze too mirrors what happens as we focus on the slathered pigments on the canvas surface and through them, past them, to the imputed image beyond: the pool, the patio, the sandals, the steps, the towel, the palms—all of them, all of it, just so many pigments in play and yet so much more).

more here.

The Violent Faith of Cormac McCarthy

J.C. Scharl at Religion And Liberty:

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry.

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry.

Specifically, his writing is elegiac. An elegy is a poetic song of something lost or passing away; it is an act of deliberate, careful recording, a close look at what is gone so we can fix its virtues in our mind before time obliterates even the memory of what used to be.

McCarthy is a master of the elegiac sentence, the vivid description that is itself a piling up of themes (in his case, almost always tragic themes), the sentence in which the metonymy or the synecdoche or the metaphor is so perfectly realized that there is no linguistic bridge between what is and what is meant, in which the description is a farewell.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

—After Carlos Drummond De Andrade

Innermost

Within everything, something prior.

Within the sizzle of nerve, a remnant

of remote pox, and at the heart

of malaise, the mosquito’s

pierce and draw.

Within the swimmer’s breath,

the impulse of gills.

In the middle of the vacation,

fear of running out.

In the potential circumference

of a kick, the dog’s caution.

Within the loop of scarf, bruises.

Within safety, its counterpoint.

Within the forage,

the delusion of past fullness.

Within language, tongues,

and their longing.

Within the eye, a reservoir,

a dumpster.

Within surrender, the next rebellion.

Within the fig’s gluey heart,

a speck of dead wasp.

by Shirley Stephenson

from Bodega Magazine

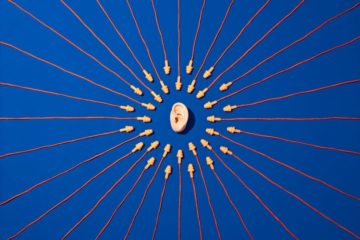

Simon & Garfunkel – Sound Of Silence (1965)

Silence Is a ‘Sound’ You Hear

Bethany Brookshire in The New York Times:

The hush at the end of the musical performance. The pause in a dramatic speech. The muted moment when you turn off the car. What is it that we hear when we hear nothing at all? Are we detecting silence? Or are we just hearing nothing and interpreting that absence as silence?

The hush at the end of the musical performance. The pause in a dramatic speech. The muted moment when you turn off the car. What is it that we hear when we hear nothing at all? Are we detecting silence? Or are we just hearing nothing and interpreting that absence as silence?

The “Sound of Silence” is a philosophical question that made for one of Simon & Garfunkel’s most enduring songs, but it’s also a subject that can be tested by psychologists. In a paper published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers used a series of sonic illusions to show that people perceive silences much as they hear sounds. While the study offers no insight into how our brains might be processing silence, the results suggest that people perceive silence as its own type of “sound,” not just as a gap between noises.

‘The vision that was planted in my brain still remains’

Rui Zhe Goh, a graduate student in cognitive science and philosophy at Johns Hopkins University and one of the scientists involved in the study, described a koan that he likes: “Silence is the experience of time passing.” He said he interprets that to mean that silence is “an auditory experience of pure time.”

More here.

Sunday, July 9, 2023

Thomas Pynchon as America’s Theologian

Alan Jacobs in The Hedgehog Review:

In 1988, the great Lutheran scholar Robert Jenson published a book called America’s Theologian, conferring that honor on the formidable eighteenth-century Calvinist divine Jonathan Edwards. Jenson did not mean that Edwards is the greatest American theologian, though he probably is, but rather “that Edwards’s theology meets precisely the problems and opportunities of specifically American Christianity and of the nation molded thereby, and that it does so with the profundity and inventive élan that belong only to the very greatest thinkers.”1 Quite clearly, a very different America has emerged in the decades since Jenson’s book was published, and the best theologian of our America is by profession neither a theologian nor a pastor. The great theologian of our America, I propose, is the novelist Thomas Pynchon.

In 1988, the great Lutheran scholar Robert Jenson published a book called America’s Theologian, conferring that honor on the formidable eighteenth-century Calvinist divine Jonathan Edwards. Jenson did not mean that Edwards is the greatest American theologian, though he probably is, but rather “that Edwards’s theology meets precisely the problems and opportunities of specifically American Christianity and of the nation molded thereby, and that it does so with the profundity and inventive élan that belong only to the very greatest thinkers.”1 Quite clearly, a very different America has emerged in the decades since Jenson’s book was published, and the best theologian of our America is by profession neither a theologian nor a pastor. The great theologian of our America, I propose, is the novelist Thomas Pynchon.

More here.

A.I. Is Coming for Mathematics, Too

Siobhan Roberts in the New York Times:

In 2019, Christian Szegedy, a computer scientist formerly at Google and now at a start-up in the Bay Area, predicted that a computer system would match or exceed the problem-solving ability of the best human mathematicians within a decade. Last year he revised the target date to 2026.

In 2019, Christian Szegedy, a computer scientist formerly at Google and now at a start-up in the Bay Area, predicted that a computer system would match or exceed the problem-solving ability of the best human mathematicians within a decade. Last year he revised the target date to 2026.

Akshay Venkatesh, a mathematician at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and a winner of the Fields Medal in 2018, isn’t currently interested in using A.I., but he is keen on talking about it. “I want my students to realize that the field they’re in is going to change a lot,” he said in an interview last year.

More here.

On “Mission: Impossible” and Unaccountable Government

Pat Cassels in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Over time, Ethan Hunt and his geopolitical exploits have remained a rare cultural constant through a time of real-world geopolitical upheaval. Mission: Impossible’s six installments have been with the United States across three recessions, five presidents, at least two wars, and a global pandemic. That’s the kind of longevity that transforms a franchise from a series of ephemeral blockbusters with loosely connected plots into a quasi-reliable witness to history who has stuck around long enough to recall a few important things, even if its memories are a little hazy, and for some reason all involve Ving Rhames wearing a fedora.

Over time, Ethan Hunt and his geopolitical exploits have remained a rare cultural constant through a time of real-world geopolitical upheaval. Mission: Impossible’s six installments have been with the United States across three recessions, five presidents, at least two wars, and a global pandemic. That’s the kind of longevity that transforms a franchise from a series of ephemeral blockbusters with loosely connected plots into a quasi-reliable witness to history who has stuck around long enough to recall a few important things, even if its memories are a little hazy, and for some reason all involve Ving Rhames wearing a fedora.

Of course, trying to gauge the political philosophy of the Mission: Impossible franchise is a little like trying to gauge the guests’ feelings during an orgy. Sure, they must have something on their minds, but asking would just ruin everyone’s good time. But the franchise’s unprecedented durability, combined with the fact that Mission: Impossible is, however obliquely, about a US intelligence agency (the IMF, literally the “Impossible Mission Force”), has made it an unlikely chronicler of American hegemony in the first quarter of our century—about the only thing the series has ever “quietly” done.

More here.

Sunday Poem

A Word on Statistics

Out of every hundred people

those who always know better:

fifty-two.

Unsure of every step:

almost all the rest.

Ready to help,

if it doesn’t take long:

forty-nine.

Always good,

because they cannot be otherwise:

four—well, maybe five.

Able to admire without envy:

eighteen.

Led to error

by youth (which passes):

sixty, plus or minus.

Those not to be messed with:

forty and four.

Living in constant fear

of someone or something:

seventy-seven.

Capable of happiness:

twenty-some-odd at most.

Harmless alone,

turning savage in crowds:

more than half, for sure.

Cruel

when forced by circumstances:

it’s better not to know,

not even approximately.

Wise in hindsight:

not many more

than wise in foresight.

Getting nothing out of life except things:

thirty

(though I would like to be wrong).

Doubled over in pain

and without a flashlight in the dark:

eighty-three, sooner or later.

Those who are just:

quite a few at thirty-five.

But if it takes effort to understand:

three.

Worthy of empathy:

ninety-nine.

Mortal:

one hundred out of one hundred—

a figure that has never varied yet.

by Wislawa Szymborska

translation: Joanna Trzeciak

Think being a NASCAR driver isn’t as physically demanding as other sports?

Michael Reid in The Conversation:

First, the physical effort of driving a race car is much greater than that of driving your family car.

First, the physical effort of driving a race car is much greater than that of driving your family car.

Turning and braking require more force due to the high speeds and the unique engineering of race cars. Drivers control the vehicle by constantly engaging the muscles of the arms, upper body and legs.

“There’s tremendous kick-back through the steering wheel,” IndyCar driver Dario Franchitti said in a 2012 interview, “and there’s no power steering, so every movement of the wheel requires a lot of energy.”

After being hooked up to sensors to track the stresses and strains he endured a race, Franchitti learned he needed to generate 35 pounds of force just to steer, and 135 pounds of force to brake.

More here.

Apparent Close-up

Magali Duzant in Lens Culture:

Eyes follow you from behind a slit in a translucent sheet. A tear, loosely sewn, cuts across an image. A nose emerges, and elsewhere faces float in repose, softened and semi-hidden. Overlays, cuts, and stitches in the smoky surface create a game of hide and seek. Perhaps we’ve caught someone mid-dream, but who? The person in the portrait or the artist herself?

Eyes follow you from behind a slit in a translucent sheet. A tear, loosely sewn, cuts across an image. A nose emerges, and elsewhere faces float in repose, softened and semi-hidden. Overlays, cuts, and stitches in the smoky surface create a game of hide and seek. Perhaps we’ve caught someone mid-dream, but who? The person in the portrait or the artist herself?

The photographic work of Cathy Cone plays with consciousness. Images shift, twist, and transform in her studio, their depths revealed through the artist’s material interventions. In her recent series, Apparent Close-Up, she combines portraiture, found imagery, paint, vellum, and thread. The resulting prints dance along the edge of a threshold, reeling between the known and unknown, between visibility and obscurity. Doubling abounds in these images as if hinting at the world of dreams and all that lurks below the surface. The portraits force the viewer to question what they are searching for and what form of intimacy they may desire in the act of looking.

More here.

I Dated 100 American Men. Here’s How They’re Different to Brits

Rochelle Peachey in Newsweek:

There I was, sitting in a New Jersey Burger King, while the restaurant manager I was on a date shouted the lyrics to Rule, Britannia! at the top of his lungs. I had just started eating my Whopper meal when he started belting it out, his arms firmly placed on my shoulders. “She’s British! She’s British,” he shouted at the various people who were just getting on with their day, but were clearly wondering what on earth was going on. Well, this is going to be fantastic, I thought. I was in my mid-40s at the time, and had no real plan other than which states I would be visiting, placing newspaper adverts in New York, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Miami, and Philadelphia claiming to be a single woman looking for love.

There I was, sitting in a New Jersey Burger King, while the restaurant manager I was on a date shouted the lyrics to Rule, Britannia! at the top of his lungs. I had just started eating my Whopper meal when he started belting it out, his arms firmly placed on my shoulders. “She’s British! She’s British,” he shouted at the various people who were just getting on with their day, but were clearly wondering what on earth was going on. Well, this is going to be fantastic, I thought. I was in my mid-40s at the time, and had no real plan other than which states I would be visiting, placing newspaper adverts in New York, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Miami, and Philadelphia claiming to be a single woman looking for love.

I hoped everyone would be as weird and wonderful as the man I’d met in that Burger King, and they did not disappoint. One gentleman, after a couple of drinks, informed me that he had taken the liberty of booking a hotel room for us after knowing me for only a couple of hours—I politely declined. Another was fidgeting so much at lunch that I had to ask what was wrong.

“Take your coat off?” I suggested.

“No. I’ve got my dead cat in there,” he replied.

More here.

Coco Lee (1975 – 2023) Singer and Actor

Alan Arkin (1934 – 2023) Actor

Peter Brötzmann (1941 – 2023) Saxophonist

Saturday, July 8, 2023

The Upper West Side Cult That Hid in Plain Sight

Jessica Winter in The New Yorker:

Jessica Winter in The New Yorker:

Cults thrive in isolation, and this poses a challenge for the urban cult leader. Jim Jones, of the Peoples Temple, exerted an unsettling degree of influence on San Francisco politics of the late nineteen-seventies but was eventually forced to flee to his doomed jungle outpost in Guyana. Charles Manson made halting inroads in the late-sixties Los Angeles music scene while his Family hunkered down on the fifty-five-acre Spahn Movie Ranch. Scientology has prominent real-estate holdings in major cities across the world, but its élite management unit, the Sea Org, was originally intended to operate in international waters, in order to evade government and media scrutiny.

At its peak, in the mid- to late seventies, the psychoanalytic association known as the Sullivanian Institute had as many as six hundred patient-members clustered in apartment buildings that the group bought or rented on the cheap on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. They also ran an experimental theatre troupe, called the Fourth Wall, on the Lower East Side. The Sullivanians adhered to the same principles and traditions as many of the ashrams and rural intentional communities of the era: polyamory, communal living, group parenting, socialist politics. But they came to their belief system through the gateway of psychoanalysis, the self-actualization tool of the urbane intellectual. And they enacted their beliefs on a crowded concrete island of nearly a million and a half people, often while holding down high-status jobs as physicians, attorneys, computer programmers, and academics. The institute’s co-founder and reigning tyrant, Saul Newton, who sat atop the organization from the mid-nineteen-fifties until the mid-nineteen-eighties (he died in 1991), may have come closer than any of his far more notorious peers to establishing a truly metropolitan cult—its members visible but its practices obscure.

More here.

Body and Soul

Jack Arden in Sidecar:

Jack Arden in Sidecar:

Last month, in purple passages lauding ‘a master stylist, whose use of punctuation was an art form in itself’, whose literary career was powered by a ‘supercharged prose, all heft and twang’, the usually characterless British broadsheets succumbed to the charms of ‘style’. Journalistic prose gave way to overwriting, as if the subject – the death of Martin Amis – provided a pretext for some formal indulgence, the effusion of pent-up lyricism. If opinions differed as to the quality of his books or the value of his political interventions, all could agree that Amis’s sentences were ‘dazzling’. In these eulogies, style was invariably interpreted as a kind of personal touch, a reflection of the writer’s singular identity: ‘The style was the man’, Sebastian Faulks told The Times. Yet such unanimity created the impression that style was also more than this – something supra-personal, perhaps a class-bound argot, expressed in the shared valediction for Amis’s verbal gifts.

In his obituary for Sidecar, Thomas Meaney added a critical note to the chorus of praise. Amis ‘occasionally succumbed to the literary equivalent of quantitative easing – inflating his sentences with adjectives as if to ward off the collapse of the books that housed them’. The dichotomy, between Amis’s ‘high-flown English’ and its opposite, is a long-standing one. Here the image of inflationary adjectives presumes some ‘real economy’ of plain style, in which parts of speech can find their ‘natural rate’. Judgements about style are often structured around these two dependent poles: at one end, the flowery, the overwritten, the self-reflexive or even autotelic; and at the other, the plain, the clear, the concise and the communicative. Does this distinction, seemingly embedded in our common sense, withstand scrutiny?

More here.