Nicholas Jepson in Phenomenal World:

At the start of her three-nation tour of Africa this January, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen spoke to the Associated Press in Senegal, bemoaning the “piling, unsustainable debt” that, she said, “plagued” many African countries. This was a problem, she argued, “related to Chinese investments in Africa.” Two days later Yellen was in Zambia, a country which, having defaulted on its external debt in 2020, was still trying to clinch a final deal with creditors more than two years later. In 2021 the G20 had agreed on the Common Framework, a vague set of guidelines meant to smooth such restructuring talks among low-income debtors and a variety of creditors, each with sometimes contradictory demands. If successful, Yellen stressed, such negotiations would unlock much needed disbursements from a $1.3 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan. The problem, according to Yellen, was that China had become a “barrier to concluding the negotiations.” Back in the US, World Bank President David Malpass told Bloomberg that “China is asking lots of questions in the creditors committees, and that causes delays, that strings out the process.” The following day, the Chinese Embassy in Lusaka released a statement defending China’s role in the Zambian talks, chiding Yellen over US debt ceiling uncertainties and advising that “the biggest contribution that the US can make to the debt issues outside the country is to act on responsible monetary policies, cope with its own debt problem, and stop sabotaging other sovereign countries’ active efforts to solve their debt issues.” In this context, it is hardly surprising that ex-Zambian trade minister Dipak Patel has complained of his country becoming a pawn in a “Common Framework Cold War.”

Global sovereign debt crises are not a new phenomenon. They date as far back as the Panic of 1825, when a wave of defaults by newly independent Latin American states contributed to a financial crisis in London that came close to collapsing the Bank of England.

More here.

Jon Raymond: Let’s start simple. How far back does your fascination with Nevelson go? Were there any pivotal moments that led you to write this book? Any signs or portents that guided you?

Jon Raymond: Let’s start simple. How far back does your fascination with Nevelson go? Were there any pivotal moments that led you to write this book? Any signs or portents that guided you? The controversies that have haunted the publication of Heidegger’s work are significant, insofar as they concern not merely occasional and understandable editorial lapses but instead suggest a premeditated policy of substantive editorial cleansing: a strategy whose goal was to systematically and deliberately excise Heidegger’s pro-Nazi sentiments and convictions. As Heidegger scholar Otto Pöggeler observed appositely, “Heidegger is like a fox who sweeps away his traces with his tail.”

The controversies that have haunted the publication of Heidegger’s work are significant, insofar as they concern not merely occasional and understandable editorial lapses but instead suggest a premeditated policy of substantive editorial cleansing: a strategy whose goal was to systematically and deliberately excise Heidegger’s pro-Nazi sentiments and convictions. As Heidegger scholar Otto Pöggeler observed appositely, “Heidegger is like a fox who sweeps away his traces with his tail.” B

B The Hasidim more than other Jewish sects are committed to a life after death—some believe that dead souls can appear to the living. In the oldest Jewish traditions, though, there is little emphasis on a next life; there are almost no revenants or ghosts in the Hebrew Bible, and no afterlife that impresses us as being more than a name for death itself—Sheol is as featureless and blind and inactive as the grave it stands for. The tradition of the soul’s escape from the earth and the body through the spheres derives from Neoplatonic philosophers of late antiquity; I don’t know how it might have become implicated in the funerary rites of the Lubavitcher Hasidim, and no other rabbi I’ve talked to has ever heard of this explanation for the practice, but I was there on that day, giving aid to a soul on its journey. And yet I also know that on the anniversaries of his death, the man I helped to bury is visited by his relations, who place small rocks on his headstone, and pray that he may rest there in peace.

The Hasidim more than other Jewish sects are committed to a life after death—some believe that dead souls can appear to the living. In the oldest Jewish traditions, though, there is little emphasis on a next life; there are almost no revenants or ghosts in the Hebrew Bible, and no afterlife that impresses us as being more than a name for death itself—Sheol is as featureless and blind and inactive as the grave it stands for. The tradition of the soul’s escape from the earth and the body through the spheres derives from Neoplatonic philosophers of late antiquity; I don’t know how it might have become implicated in the funerary rites of the Lubavitcher Hasidim, and no other rabbi I’ve talked to has ever heard of this explanation for the practice, but I was there on that day, giving aid to a soul on its journey. And yet I also know that on the anniversaries of his death, the man I helped to bury is visited by his relations, who place small rocks on his headstone, and pray that he may rest there in peace. In Peter Singer’s paper,

In Peter Singer’s paper,  Given India’s long coastline and its total reliance on predictable patterns of rainfall and steady rates of snow-replenished, glacial meltwater to feed its people, the mounting threats of climate change are real and urgent. It behoves us, as a nation, to take aggressive action to mitigate these threats by reducing our use of coal, oil and gas, by preserving and expanding mature forests. But, given that we demand more electricity and gasoline to power our increasingly urban, consumerist lives while pursuing a model of development based on pulling more people into energy-intensive lifestyles, the central government has declared its intention to more than double energy generation capacity by 2030, mostly by rapidly expanding low-carbon energy sources. As a low-emissions, renewable resource, the Polavaram dam might be regarded as an example of “green” energy, never mind its immense ecological and human costs.

Given India’s long coastline and its total reliance on predictable patterns of rainfall and steady rates of snow-replenished, glacial meltwater to feed its people, the mounting threats of climate change are real and urgent. It behoves us, as a nation, to take aggressive action to mitigate these threats by reducing our use of coal, oil and gas, by preserving and expanding mature forests. But, given that we demand more electricity and gasoline to power our increasingly urban, consumerist lives while pursuing a model of development based on pulling more people into energy-intensive lifestyles, the central government has declared its intention to more than double energy generation capacity by 2030, mostly by rapidly expanding low-carbon energy sources. As a low-emissions, renewable resource, the Polavaram dam might be regarded as an example of “green” energy, never mind its immense ecological and human costs. When Western leaders welcomed China into the World Trade Organization in 2001, most assumed that they were creating the conditions for eventual democratization. A growing Chinese middle class, they assumed, would demand greater accountability from the government, ultimately creating so much pressure that the autocrats would step aside and allow for a democratic transition. This political fantasy underpinned the Sino-American relationship for decades.

When Western leaders welcomed China into the World Trade Organization in 2001, most assumed that they were creating the conditions for eventual democratization. A growing Chinese middle class, they assumed, would demand greater accountability from the government, ultimately creating so much pressure that the autocrats would step aside and allow for a democratic transition. This political fantasy underpinned the Sino-American relationship for decades. The book is not just about owls, though, but about the people who study them. There are many scientists and conservationists, who have, like Ackerman, fallen under the spell of these endearing creatures. People like José Luis Peña, a neuroscientist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in New York, who has discovered that a barn owl’s sound localisation system relies on sophisticated mathematical computations to pinpoint its prey. Or zoomusicologist Magnus Robb, who studies hoots.

The book is not just about owls, though, but about the people who study them. There are many scientists and conservationists, who have, like Ackerman, fallen under the spell of these endearing creatures. People like José Luis Peña, a neuroscientist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in New York, who has discovered that a barn owl’s sound localisation system relies on sophisticated mathematical computations to pinpoint its prey. Or zoomusicologist Magnus Robb, who studies hoots. When setting out to write “A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy and War at Oxford, 1900-1960,” Nikhil Krishnan certainly had his work cut out for him. How to generate excitement for a “much-maligned” philosophical tradition that hinges on finicky distinctions in language? Whose main figures were mostly well-to-do white men, routinely caricatured — and not always unfairly — for being suspicious of foreign ideas and imperiously, insufferably smug?

When setting out to write “A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy and War at Oxford, 1900-1960,” Nikhil Krishnan certainly had his work cut out for him. How to generate excitement for a “much-maligned” philosophical tradition that hinges on finicky distinctions in language? Whose main figures were mostly well-to-do white men, routinely caricatured — and not always unfairly — for being suspicious of foreign ideas and imperiously, insufferably smug? The sudden rise of

The sudden rise of  The James Webb Space Telescope, the largest and most sophisticated space observatory ever built, has been sending back images and data for almost a full year now—and in that time it has delivered a treasure trove of information about everything from stars and planetary systems in our own galactic neighborhood to distant galaxies that formed when the universe was a tiny fraction of its current age. Webb has also sent back stunning images that surpass those garnered by its famous predecessor, the

The James Webb Space Telescope, the largest and most sophisticated space observatory ever built, has been sending back images and data for almost a full year now—and in that time it has delivered a treasure trove of information about everything from stars and planetary systems in our own galactic neighborhood to distant galaxies that formed when the universe was a tiny fraction of its current age. Webb has also sent back stunning images that surpass those garnered by its famous predecessor, the  An assassin works from a partial understanding of the world. If not literally a hashishi, as suggested by the word’s etymology, an assassin must nevertheless see the world in tunnel vision, his victim viewed through the lens of a scope. The vast, complex network of humanity to which he and his victim belong, with contending narratives and blurred individual motives, cannot be allowed to exist. To do so would be to fail as an assassin.

An assassin works from a partial understanding of the world. If not literally a hashishi, as suggested by the word’s etymology, an assassin must nevertheless see the world in tunnel vision, his victim viewed through the lens of a scope. The vast, complex network of humanity to which he and his victim belong, with contending narratives and blurred individual motives, cannot be allowed to exist. To do so would be to fail as an assassin. We cannot be sure what animals are, because we cannot be sure what we are. We are beasts among beasts, and something qualitatively different. The boundary between these two kinds of being is always ready to dissolve by moonlight.

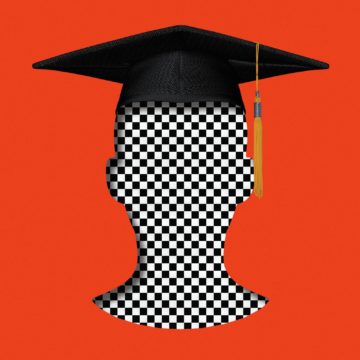

We cannot be sure what animals are, because we cannot be sure what we are. We are beasts among beasts, and something qualitatively different. The boundary between these two kinds of being is always ready to dissolve by moonlight. The Supreme Court last week outlawed the use of race-based affirmative action in college admissions. That practice was understandable and even necessary 60 years ago. The question I have asked for some time was precisely how long it would be required to continue. I’d personally come to believe that preferences focused on socioeconomic factors — wealth, income, even neighborhood — would accomplish more good while requiring less straightforward unfairness.

The Supreme Court last week outlawed the use of race-based affirmative action in college admissions. That practice was understandable and even necessary 60 years ago. The question I have asked for some time was precisely how long it would be required to continue. I’d personally come to believe that preferences focused on socioeconomic factors — wealth, income, even neighborhood — would accomplish more good while requiring less straightforward unfairness. Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887),

Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887),