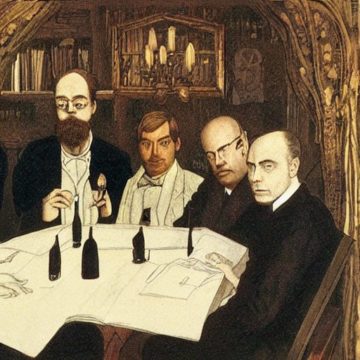

Jack Arden in Sidecar:

Jack Arden in Sidecar:

Last month, in purple passages lauding ‘a master stylist, whose use of punctuation was an art form in itself’, whose literary career was powered by a ‘supercharged prose, all heft and twang’, the usually characterless British broadsheets succumbed to the charms of ‘style’. Journalistic prose gave way to overwriting, as if the subject – the death of Martin Amis – provided a pretext for some formal indulgence, the effusion of pent-up lyricism. If opinions differed as to the quality of his books or the value of his political interventions, all could agree that Amis’s sentences were ‘dazzling’. In these eulogies, style was invariably interpreted as a kind of personal touch, a reflection of the writer’s singular identity: ‘The style was the man’, Sebastian Faulks told The Times. Yet such unanimity created the impression that style was also more than this – something supra-personal, perhaps a class-bound argot, expressed in the shared valediction for Amis’s verbal gifts.

In his obituary for Sidecar, Thomas Meaney added a critical note to the chorus of praise. Amis ‘occasionally succumbed to the literary equivalent of quantitative easing – inflating his sentences with adjectives as if to ward off the collapse of the books that housed them’. The dichotomy, between Amis’s ‘high-flown English’ and its opposite, is a long-standing one. Here the image of inflationary adjectives presumes some ‘real economy’ of plain style, in which parts of speech can find their ‘natural rate’. Judgements about style are often structured around these two dependent poles: at one end, the flowery, the overwritten, the self-reflexive or even autotelic; and at the other, the plain, the clear, the concise and the communicative. Does this distinction, seemingly embedded in our common sense, withstand scrutiny?

More here.