Meg Tirrell in CNN:

Cheri Ferguson has traded her vape pen for an Ozempic pen. One day seven weeks ago, “I thought, ‘you’re doing something about your weight; leave your vape at home,’ ” Ferguson said. She hasn’t picked it back up since, she says. Ferguson is one of many people taking Ozempic and similar drugs for weight loss who say they’ve also noticed an effect on their interest in addictive behaviors like smoking and alcohol. A smoker for most of her life, Ferguson started Ozempic 11 weeks ago to try to lose about 50 pounds she’d gained during the Covid-19 pandemic, which had made her prediabetic.

Cheri Ferguson has traded her vape pen for an Ozempic pen. One day seven weeks ago, “I thought, ‘you’re doing something about your weight; leave your vape at home,’ ” Ferguson said. She hasn’t picked it back up since, she says. Ferguson is one of many people taking Ozempic and similar drugs for weight loss who say they’ve also noticed an effect on their interest in addictive behaviors like smoking and alcohol. A smoker for most of her life, Ferguson started Ozempic 11 weeks ago to try to lose about 50 pounds she’d gained during the Covid-19 pandemic, which had made her prediabetic.

She’d switched from cigarettes to vaping last summer in hopes of quitting but found vapes to be even more addictive. That changed, she said, once she started Ozempic. “It’s like someone’s just come along and switched the light on, and you can see the room for what it is,” Ferguson said. “And all of these vapes and cigarettes that you’ve had over the years, they don’t look attractive anymore. It’s very, very strange. Very strange.” Ferguson said she drinks less alcohol on Ozempic, too. Whereas she would have had multiple drinks in a pub while watching a football match in Buckinghamshire, UK, she’s now content with just one. Some doctors say that when it comes to addictive behaviors, an effect on alcohol use is the most common thing they hear from people taking Ozempic or similar medicines.

More here.

Lydia Kiesling’s first novel,

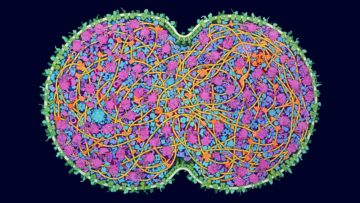

Lydia Kiesling’s first novel,  Seven years ago, researchers showed that they could strip cells down to their barest fundamentals, creating a life form with the smallest genome that still allowed it to grow and divide in the lab. But in shedding half its genetic load, that “minimal” cell also lost some of the hardiness and adaptability that natural life evolved over billions of years. That left biologists wondering whether the reduction might have been a one-way trip: In pruning the cells down to their bare essentials, had they left the cells incapable of evolving because they could not survive a change in even one more gene?

Seven years ago, researchers showed that they could strip cells down to their barest fundamentals, creating a life form with the smallest genome that still allowed it to grow and divide in the lab. But in shedding half its genetic load, that “minimal” cell also lost some of the hardiness and adaptability that natural life evolved over billions of years. That left biologists wondering whether the reduction might have been a one-way trip: In pruning the cells down to their bare essentials, had they left the cells incapable of evolving because they could not survive a change in even one more gene? Men, I have bad news: Caitlin Moran is coming for us. She comes not to man-bash, not to holler: ‘All men are rapists!’ It’s worse than that. She feels sorry for us. ‘I’m violently opposed to the branches of feminism that are permanently angry with men’, she writes at the very start of her very bad book. Instead she pities us. She frets over our toxic stoicism, our inability to be vulnerable, our unwillingness to be open about our fat bodies and small cocks. She wants to save us from all the ‘rules’ about ‘what a man should be’. From all that ‘swagger’ and ‘the stiff upper lip’. By the end I found myself pining for some good ol’ angry

Men, I have bad news: Caitlin Moran is coming for us. She comes not to man-bash, not to holler: ‘All men are rapists!’ It’s worse than that. She feels sorry for us. ‘I’m violently opposed to the branches of feminism that are permanently angry with men’, she writes at the very start of her very bad book. Instead she pities us. She frets over our toxic stoicism, our inability to be vulnerable, our unwillingness to be open about our fat bodies and small cocks. She wants to save us from all the ‘rules’ about ‘what a man should be’. From all that ‘swagger’ and ‘the stiff upper lip’. By the end I found myself pining for some good ol’ angry  Last month, researchers from 67 nations wrote an

Last month, researchers from 67 nations wrote an  Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s. Go to the Guggenheim Museum. Climb past the gift shops and walls of Gego and Picasso. Awaiting you on the top floor is the niftiest migraine you will ever experience. The artist responsible, Sarah Sze, has contributed a set of site-specific pieces that look like a single shantytown of projectors, plastic bottles, potted plants, paintings, photographs, papers, and pills, to name only a handful of the “P”s. There are thousands of other bits, many of them mass-produced tools doing any job but the one they were made for. Everything is stacked or fanned or strewn, and looks a sneeze away from collapse. Red clamps and blue tape take credit for the hard work done by secret dabs of glue, while other yips of color compete with the gray floors, and lose. Most of the installations are lit by the museum’s glow, and one isn’t lit at all, but for some reason I imagine the entire set in the prickly glare of a conference room.

Go to the Guggenheim Museum. Climb past the gift shops and walls of Gego and Picasso. Awaiting you on the top floor is the niftiest migraine you will ever experience. The artist responsible, Sarah Sze, has contributed a set of site-specific pieces that look like a single shantytown of projectors, plastic bottles, potted plants, paintings, photographs, papers, and pills, to name only a handful of the “P”s. There are thousands of other bits, many of them mass-produced tools doing any job but the one they were made for. Everything is stacked or fanned or strewn, and looks a sneeze away from collapse. Red clamps and blue tape take credit for the hard work done by secret dabs of glue, while other yips of color compete with the gray floors, and lose. Most of the installations are lit by the museum’s glow, and one isn’t lit at all, but for some reason I imagine the entire set in the prickly glare of a conference room. On a muggy June night in Greenwich Village, more than 800 neuroscientists, philosophers and curious members of the public packed into an auditorium. They came for the first results of an ambitious investigation into a profound question: What is consciousness?

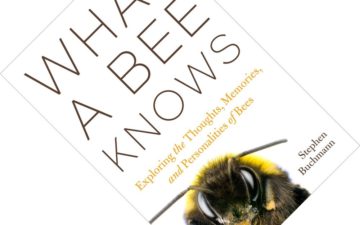

On a muggy June night in Greenwich Village, more than 800 neuroscientists, philosophers and curious members of the public packed into an auditorium. They came for the first results of an ambitious investigation into a profound question: What is consciousness? The collectives formed by social insects fascinate us, whether it is bees, ants, or termites. But it would be a mistake to think that the individuals making up such collectives are just mindless cogs in a bigger machine. It is entirely reasonable to ask, as pollination ecologist Stephen Buchmann does here, what a bee knows. This book was published almost a year after Lars Chittka’s

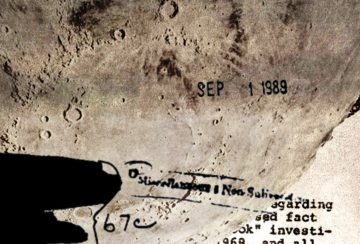

The collectives formed by social insects fascinate us, whether it is bees, ants, or termites. But it would be a mistake to think that the individuals making up such collectives are just mindless cogs in a bigger machine. It is entirely reasonable to ask, as pollination ecologist Stephen Buchmann does here, what a bee knows. This book was published almost a year after Lars Chittka’s  There have been two dominant narratives about the rise of misinformation and conspiracy theories in American public life.

There have been two dominant narratives about the rise of misinformation and conspiracy theories in American public life. We just want to call everyone’s attention to the rolling nationwide release this week and over the next several (for a complete list of cities and venues see

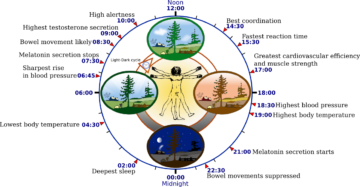

We just want to call everyone’s attention to the rolling nationwide release this week and over the next several (for a complete list of cities and venues see  Over the last few years, there has been a groundswell of podcasts, wellness apps and self-improvement social media videos alerting a mass audience to the potential of applying circadian science. It was a

Over the last few years, there has been a groundswell of podcasts, wellness apps and self-improvement social media videos alerting a mass audience to the potential of applying circadian science. It was a In July 1971, the British cybernetician Stafford Beer received an unexpected letter from Chile. Its contents would dramatically change Beer’s life. The writer was a young Chilean engineer named Fernando Flores, who was working for the government of newly elected Socialist president Salvador Allende. Flores wrote that he was familiar with Beer’s work in management cybernetics and was “now in a position from which it is possible to implement on a national scale—at which cybernetic thinking becomes a necessity—scientific views on management and organization.” Flores asked Beer for advice on how to apply cybernetics to the management of the nationalized sector of the Chilean economy, which was expanding quickly because of Allende’s aggressive nationalization policy.

In July 1971, the British cybernetician Stafford Beer received an unexpected letter from Chile. Its contents would dramatically change Beer’s life. The writer was a young Chilean engineer named Fernando Flores, who was working for the government of newly elected Socialist president Salvador Allende. Flores wrote that he was familiar with Beer’s work in management cybernetics and was “now in a position from which it is possible to implement on a national scale—at which cybernetic thinking becomes a necessity—scientific views on management and organization.” Flores asked Beer for advice on how to apply cybernetics to the management of the nationalized sector of the Chilean economy, which was expanding quickly because of Allende’s aggressive nationalization policy. People have complicated relationships with hairy skin moles. For some, they symbolize individuality and good fortune. For others, a bothersome blemish. Maksim Plikus, a professor of developmental and cell biology at the University of California, Irvine regards these mounds of wild-growing hair as islands of knowledge. His curiosity and astuteness compelled him to look closer at a biological anomaly that others overlooked. “Nothing exists for no reason. There is some really interesting biology hidden in everything,” Plikus said. Skin moles are common growths that contain clusters of melanocytes, the skin’s pigment producing cells. These melanocytes are

People have complicated relationships with hairy skin moles. For some, they symbolize individuality and good fortune. For others, a bothersome blemish. Maksim Plikus, a professor of developmental and cell biology at the University of California, Irvine regards these mounds of wild-growing hair as islands of knowledge. His curiosity and astuteness compelled him to look closer at a biological anomaly that others overlooked. “Nothing exists for no reason. There is some really interesting biology hidden in everything,” Plikus said. Skin moles are common growths that contain clusters of melanocytes, the skin’s pigment producing cells. These melanocytes are