Julie Miller in Vanity Fair:

It was nearing eight o’clock in the evening on December 11, 1981, and the serial killer Stephen Morin was driving the SUV of his latest captive, Margy Palm, north out of San Antonio. Helicopters circled the city and police combed the streets, warning people to stay inside and lock the doors. Morin’s reign of terror was sputtering to a clumsy close after a rare mistake earlier that day. He was suspected of the murder, torture, and in some cases rape of more than 30 women in 9 or 10 states—and most of San Antonio now knew that he was on the loose in its manicured, country-club midst.

It was nearing eight o’clock in the evening on December 11, 1981, and the serial killer Stephen Morin was driving the SUV of his latest captive, Margy Palm, north out of San Antonio. Helicopters circled the city and police combed the streets, warning people to stay inside and lock the doors. Morin’s reign of terror was sputtering to a clumsy close after a rare mistake earlier that day. He was suspected of the murder, torture, and in some cases rape of more than 30 women in 9 or 10 states—and most of San Antonio now knew that he was on the loose in its manicured, country-club midst.

Morin’s concern at the moment, though, wasn’t escaping so much as finding an appropriate soundtrack for his kidnapping of Palm, the 30-year-old Texan in the passenger seat. Morin, also 30, had pulled a .38 revolver on her six hours earlier as she reached her Chevy Suburban in the parking lot of a Kmart after Christmas shopping, then shoved her inside the car. Palm looked like many of his other victims—pretty, fit, and blond—and tells me that she didn’t try to fight or flee for the same reason that some of the others hadn’t: “I’ve never felt that kind of fear.”

More here.

Russell Moore, editor-in-chief of Christianity Today and a former stalwart of the American Baptist church, said during an interview this month that

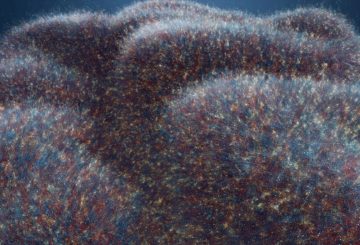

Russell Moore, editor-in-chief of Christianity Today and a former stalwart of the American Baptist church, said during an interview this month that  It took 10 years, around 500 scientists and some €600 million, and now the Human Brain Project — one of the biggest research endeavours ever funded by the European Union — is coming to an end. Its audacious goal was to understand the human brain by modelling it in a computer. During its run, scientists under the umbrella of the Human Brain Project (HBP) have published thousands of papers and made significant strides in neuroscience, such as creating detailed 3D maps of at least 200 brain regions

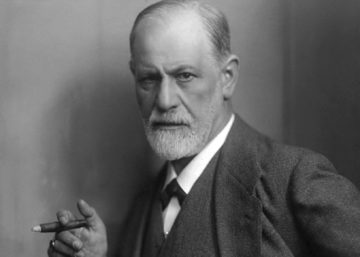

It took 10 years, around 500 scientists and some €600 million, and now the Human Brain Project — one of the biggest research endeavours ever funded by the European Union — is coming to an end. Its audacious goal was to understand the human brain by modelling it in a computer. During its run, scientists under the umbrella of the Human Brain Project (HBP) have published thousands of papers and made significant strides in neuroscience, such as creating detailed 3D maps of at least 200 brain regions Lear is not to first to link the question of whether or not to mourn to speculation about the nature of value. Here, he traces that connection to a 1915 essay by Sigmund Freud, “On Transience,” that marks a second, if still somehow cryptic, focus of Imagining the End. Freud begins his essay by recounting a conversation in the Alpine countryside with a “young poet” who startled him by refusing to take pleasure in the beauties of the landscape because, he said, they are fleeting. Freud responded with the equally extreme assertion that “transience” is the source of all value. By the close of the essay, however, writing from what he now reveals are the depths of a devastating world war, Freud has adopted a chastened view. Unlike the poet, in whom he found a fear of the pain of mourning so great that it barred all attachment, Freud’s hope now, transcending the earlier dichotomy, is that what war has destroyed may one day be rebuilt, not eternally, but “perhaps on more solid ground and more enduringly than before.”

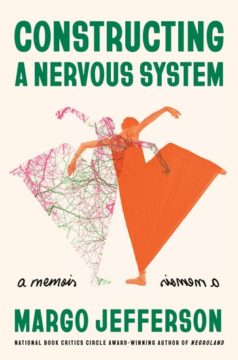

Lear is not to first to link the question of whether or not to mourn to speculation about the nature of value. Here, he traces that connection to a 1915 essay by Sigmund Freud, “On Transience,” that marks a second, if still somehow cryptic, focus of Imagining the End. Freud begins his essay by recounting a conversation in the Alpine countryside with a “young poet” who startled him by refusing to take pleasure in the beauties of the landscape because, he said, they are fleeting. Freud responded with the equally extreme assertion that “transience” is the source of all value. By the close of the essay, however, writing from what he now reveals are the depths of a devastating world war, Freud has adopted a chastened view. Unlike the poet, in whom he found a fear of the pain of mourning so great that it barred all attachment, Freud’s hope now, transcending the earlier dichotomy, is that what war has destroyed may one day be rebuilt, not eternally, but “perhaps on more solid ground and more enduringly than before.” THRALL IS A JEFFERSONIAN WORD. In Constructing a Nervous System, the critic Margo Jefferson is enthralled by or to: her mother, her father, Bing Crosby. She suspects Condoleezza Rice is enthralled by or to George W. Bush, and Ike Turner by or to “manic depression and drug addiction, to years of envy, . . . to a Mississippi childhood that was a trifecta of domestic abuse, sexual treachery and racist violence.” A young James Baldwin enthralled the Harlem faithful. Nina Simone refused the thrall of “warring desires.” It’s the last that clarifies the stakes. Thrall, some time after it meant “slave” to Northern Europeans, found a new Gothic use. Dracula, through hypnosis and sheer erotic power, holds his servants and whole towns in his thrall, the better to protect him while he hides from the sun. Those enthralled submit totally, pleasurably. Influence doesn’t always have to provoke anxiety. There is danger of losing oneself, of being absorbed by the force of another’s will and gaze and magnetism, and that’s before they seize upon your neck. But there’s a reason Dracula persists. Beneath our regimens of self-help, self-care, and self-improvement, we might think briefly of annihilation and find it sweet.

THRALL IS A JEFFERSONIAN WORD. In Constructing a Nervous System, the critic Margo Jefferson is enthralled by or to: her mother, her father, Bing Crosby. She suspects Condoleezza Rice is enthralled by or to George W. Bush, and Ike Turner by or to “manic depression and drug addiction, to years of envy, . . . to a Mississippi childhood that was a trifecta of domestic abuse, sexual treachery and racist violence.” A young James Baldwin enthralled the Harlem faithful. Nina Simone refused the thrall of “warring desires.” It’s the last that clarifies the stakes. Thrall, some time after it meant “slave” to Northern Europeans, found a new Gothic use. Dracula, through hypnosis and sheer erotic power, holds his servants and whole towns in his thrall, the better to protect him while he hides from the sun. Those enthralled submit totally, pleasurably. Influence doesn’t always have to provoke anxiety. There is danger of losing oneself, of being absorbed by the force of another’s will and gaze and magnetism, and that’s before they seize upon your neck. But there’s a reason Dracula persists. Beneath our regimens of self-help, self-care, and self-improvement, we might think briefly of annihilation and find it sweet. Nuclear war has returned to the realm of dinner table conversation, weighing on the minds of the public more than it has in a generation.

Nuclear war has returned to the realm of dinner table conversation, weighing on the minds of the public more than it has in a generation. The director Lizzie Gottlieb was hosting a birthday party for her father, the renowned editor Robert Gottlieb at her Brooklyn brownstone when she struck up a conversation with one of the many guests. “A lovely older gentleman came up to me and said, ‘What do you think of the Barclay’s Center on Flatbush Avenue and how do you think it’ll affect the neighborhood?’ I started spouting completely uninformed, random opinions.” Mid-sentence, she came to a realization. “It was Robert Caro, and I was talking to him about New York City infrastructure.”

The director Lizzie Gottlieb was hosting a birthday party for her father, the renowned editor Robert Gottlieb at her Brooklyn brownstone when she struck up a conversation with one of the many guests. “A lovely older gentleman came up to me and said, ‘What do you think of the Barclay’s Center on Flatbush Avenue and how do you think it’ll affect the neighborhood?’ I started spouting completely uninformed, random opinions.” Mid-sentence, she came to a realization. “It was Robert Caro, and I was talking to him about New York City infrastructure.” THE FINNISH PHOTOGRAPHER and video artist Iiu Susiraja’s first US solo museum exhibition,

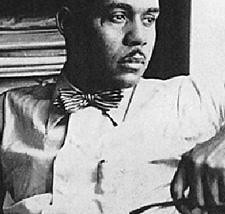

THE FINNISH PHOTOGRAPHER and video artist Iiu Susiraja’s first US solo museum exhibition,  As Ellison would teach his European pupils in Salzburg, the existence of many diverse communities rendered his native land richly heterogeneous—a veritable “international country”—and also testified to an ongoing and still challenging attempt at reconciling color and democracy. The best of American literature, and its novels in particular, contributed to the ongoing effort to forge “unity in diversity,” and this national dilemma manifested important ties to the crises “faced…by peoples throughout the world.” “Through forging forms of the novel worthy of [American diversity],” argued Ellison in his 1953 National Book Award acceptance speech, “we anticipate the resolution of those world problems of humanity which for the moment seem…completely insoluble.” The literary instantiation of American pluralism would help teach Europeans and all the world’s peoples how to create a better future, a valuable lesson for the Salzburg students who had historically received little if any exposure to literatures of color.

As Ellison would teach his European pupils in Salzburg, the existence of many diverse communities rendered his native land richly heterogeneous—a veritable “international country”—and also testified to an ongoing and still challenging attempt at reconciling color and democracy. The best of American literature, and its novels in particular, contributed to the ongoing effort to forge “unity in diversity,” and this national dilemma manifested important ties to the crises “faced…by peoples throughout the world.” “Through forging forms of the novel worthy of [American diversity],” argued Ellison in his 1953 National Book Award acceptance speech, “we anticipate the resolution of those world problems of humanity which for the moment seem…completely insoluble.” The literary instantiation of American pluralism would help teach Europeans and all the world’s peoples how to create a better future, a valuable lesson for the Salzburg students who had historically received little if any exposure to literatures of color. Despite decades of effort by researchers in the field of computational complexity theory — the study of such questions about the intrinsic difficulty of different problems — a resolution to the P versus NP question has remained elusive. And it’s not even clear where a would-be proof should start.

Despite decades of effort by researchers in the field of computational complexity theory — the study of such questions about the intrinsic difficulty of different problems — a resolution to the P versus NP question has remained elusive. And it’s not even clear where a would-be proof should start. If I’d had to explain to myself why, with only three days to spend in Paris, I felt such an acute need to visit the home where Honoré de Balzac, a writer I wasn’t even that familiar with, had composed the bulk of The Human Comedy, a fictional project I’d barely even dipped my toes into, I’m not sure what I would have said. Probably it just seemed that if anyone would have had an interesting house, it would have been him. Open one of his novels at random, and chances are you’ll find a gratuitous description of a room and its furnishings, a flurry of signifiers that, today, can seem hard to place. Take Monsieur Grandet’s living room, for instance, as it appears in the opening chapter of Eugénie Grandet. We learn the room has two windows that “gave on to the street,” that its floor is wooden, that “grey, wooden panelling with antique moulding lined the walls from top to bottom,” that its ceiling is dominated by exposed beams. “An old copper clock, inlaid with tortoiseshell arabesques, adorned the white, badly carved, stone chimney-piece,” Balzac goes on. “Above it hung a greenish mirror, whose edges, bevelled to show its thickness, reflected a thin stream of light along an old-fashioned pier-mirror of damascened steel.” I don’t know what a pier-mirror is, and I couldn’t begin to differentiate an old-fashioned model from a sleeker, more modern one. In a sense, this feeling of being lost was part of the appeal of Balzac’s world as I’d imagined it.

If I’d had to explain to myself why, with only three days to spend in Paris, I felt such an acute need to visit the home where Honoré de Balzac, a writer I wasn’t even that familiar with, had composed the bulk of The Human Comedy, a fictional project I’d barely even dipped my toes into, I’m not sure what I would have said. Probably it just seemed that if anyone would have had an interesting house, it would have been him. Open one of his novels at random, and chances are you’ll find a gratuitous description of a room and its furnishings, a flurry of signifiers that, today, can seem hard to place. Take Monsieur Grandet’s living room, for instance, as it appears in the opening chapter of Eugénie Grandet. We learn the room has two windows that “gave on to the street,” that its floor is wooden, that “grey, wooden panelling with antique moulding lined the walls from top to bottom,” that its ceiling is dominated by exposed beams. “An old copper clock, inlaid with tortoiseshell arabesques, adorned the white, badly carved, stone chimney-piece,” Balzac goes on. “Above it hung a greenish mirror, whose edges, bevelled to show its thickness, reflected a thin stream of light along an old-fashioned pier-mirror of damascened steel.” I don’t know what a pier-mirror is, and I couldn’t begin to differentiate an old-fashioned model from a sleeker, more modern one. In a sense, this feeling of being lost was part of the appeal of Balzac’s world as I’d imagined it. Many “pro-Europeans” – that is, supporters of European integration or the “European project” in its current form – imagine that the

Many “pro-Europeans” – that is, supporters of European integration or the “European project” in its current form – imagine that the  Consciousness presents a “hard problem” to scholars. At stake is how the physical body gives rise to subjective experience. Why consciousness is “hard”, however, is uncertain. One possibility is that the challenge arises from ontology—because consciousness is a special property/substance that is irreducible to the physical. Here, I show how the “hard problem” emerges from two intuitive biases that lie deep within human psychology: Essentialism and Dualism. To determine whether a subjective experience is transformative, people judge whether the experience pertains to one’s essence, and per Essentialism, one’s essence lies within one’s body. Psychological states that seem embodied (e.g., “color vision” ∼ eyes) can thus give rise to transformative experience. Per intuitive Dualism, however, the mind is distinct from the body, and epistemic states (knowledge and beliefs) seem particularly ethereal. It follows that conscious perception (e.g., “seeing color”) ought to seem more transformative than conscious knowledge (e.g., knowledge of how color vision works). Critically, the transformation arises precisely because the conscious perceptual experience seems readily embodied (rather than distinct from the physical body, as the ontological account suggests). In line with this proposal, five experiments show that, in laypeople’s view (a) experience is transformative only when it seems anchored in the human body; (b) gaining a transformative experience effects a bodily change; and (c) the magnitude of the transformation correlates with both (i) the perceived embodiment of that experience, and (ii) with Dualist intuitions, generally. These results cannot solve the ontological question of whether consciousness is distinct from the physical. But they do suggest that the roots of the “hard problem” are partly psychological.

Consciousness presents a “hard problem” to scholars. At stake is how the physical body gives rise to subjective experience. Why consciousness is “hard”, however, is uncertain. One possibility is that the challenge arises from ontology—because consciousness is a special property/substance that is irreducible to the physical. Here, I show how the “hard problem” emerges from two intuitive biases that lie deep within human psychology: Essentialism and Dualism. To determine whether a subjective experience is transformative, people judge whether the experience pertains to one’s essence, and per Essentialism, one’s essence lies within one’s body. Psychological states that seem embodied (e.g., “color vision” ∼ eyes) can thus give rise to transformative experience. Per intuitive Dualism, however, the mind is distinct from the body, and epistemic states (knowledge and beliefs) seem particularly ethereal. It follows that conscious perception (e.g., “seeing color”) ought to seem more transformative than conscious knowledge (e.g., knowledge of how color vision works). Critically, the transformation arises precisely because the conscious perceptual experience seems readily embodied (rather than distinct from the physical body, as the ontological account suggests). In line with this proposal, five experiments show that, in laypeople’s view (a) experience is transformative only when it seems anchored in the human body; (b) gaining a transformative experience effects a bodily change; and (c) the magnitude of the transformation correlates with both (i) the perceived embodiment of that experience, and (ii) with Dualist intuitions, generally. These results cannot solve the ontological question of whether consciousness is distinct from the physical. But they do suggest that the roots of the “hard problem” are partly psychological.