Veronique Greenwood in Quanta:

Every organism responds to the world with an intricate cascade of biochemistry. There’s a source of heat here, a faint scent of food there, or the crack of a twig as something moves nearby. Each stimulus can trigger the rise of one set of molecules in an animal’s body and perhaps the fall of others. The effect ramifies, tripping feedback loops and flipping switches, until a bird leaps into the air or a bee alights on a flower. It’s a vision of biology that entranced Andreas Wagner, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Zurich, when he was still a young student.

Every organism responds to the world with an intricate cascade of biochemistry. There’s a source of heat here, a faint scent of food there, or the crack of a twig as something moves nearby. Each stimulus can trigger the rise of one set of molecules in an animal’s body and perhaps the fall of others. The effect ramifies, tripping feedback loops and flipping switches, until a bird leaps into the air or a bee alights on a flower. It’s a vision of biology that entranced Andreas Wagner, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Zurich, when he was still a young student.

“I thought that was much more fascinating than this idea that biology is about counting the number of things that are out there,” he said. “I realized biology could be about fundamental principles of organization in living systems.”

His career, which has included stints at the Santa Fe Institute and the Institute for Advanced Study in Berlin, has taken him from modeling the regulation of gene transcription in an embryo, where precision timing makes the difference between life and death, to asking how an organism can manage to evolve when any change in its genes could spell disaster.

More here.

Elon Musk

Elon Musk Last month, in the crowded back room of a bar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, the fate of humanity hung in the balance.

Last month, in the crowded back room of a bar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, the fate of humanity hung in the balance. Michaels is intimately acquainted with this power, having spent the last half-century using SNL to launch bankable talents and profit from their careers. Bupkis isn’t just a Pete Davidson vehicle; it’s a Lorne Michaels production. So is Staten Island Summer, for that matter, and Shrill, The Tonight Show, Schmigadoon!, and That Damn Michael Che—not to mention the recently departed The Other Two and Kenan. The promise of SNL under Michaels’ leadership is simple: If you are loyal to the family, you will reap handsome rewards. Over almost 50 years, that promise has come to justify a legacy of alleged workplace abuses ranging from the familiar to the shocking. Beyond 30 Rock’s walls, it has become the promise of the massive live comedy ecosystem feeding SNL, an amorphous network of small businesses that successfully encoded their exploitative labor practices and regressive cultural norms into the industry’s DNA. As they churned ruthlessly through generations of comedy workers, they helped create the world we’re in now, the one Hollywood writers and actors are striking to change. It’s a world where talent and hard work aren’t nearly enough to earn a stable living; a world where a few fabulously wealthy men hold the power to shape entire art forms in their image.

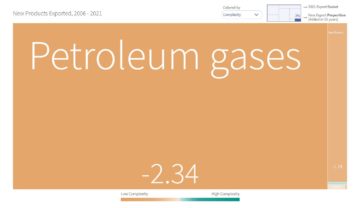

Michaels is intimately acquainted with this power, having spent the last half-century using SNL to launch bankable talents and profit from their careers. Bupkis isn’t just a Pete Davidson vehicle; it’s a Lorne Michaels production. So is Staten Island Summer, for that matter, and Shrill, The Tonight Show, Schmigadoon!, and That Damn Michael Che—not to mention the recently departed The Other Two and Kenan. The promise of SNL under Michaels’ leadership is simple: If you are loyal to the family, you will reap handsome rewards. Over almost 50 years, that promise has come to justify a legacy of alleged workplace abuses ranging from the familiar to the shocking. Beyond 30 Rock’s walls, it has become the promise of the massive live comedy ecosystem feeding SNL, an amorphous network of small businesses that successfully encoded their exploitative labor practices and regressive cultural norms into the industry’s DNA. As they churned ruthlessly through generations of comedy workers, they helped create the world we’re in now, the one Hollywood writers and actors are striking to change. It’s a world where talent and hard work aren’t nearly enough to earn a stable living; a world where a few fabulously wealthy men hold the power to shape entire art forms in their image. A useful tool from Harvard’s Growth Lab:

A useful tool from Harvard’s Growth Lab: J. Howard Rosier interviews Adam Shatz about solidarity, the art of the essay, and his recent collection Writers and Missionaries in The Nation:

J. Howard Rosier interviews Adam Shatz about solidarity, the art of the essay, and his recent collection Writers and Missionaries in The Nation: Branko Milanovic over at his Substack:

Branko Milanovic over at his Substack:

Do you know what makes you attractive? Your best features are the

Do you know what makes you attractive? Your best features are the  We could all use a hype man like George Henry Lewes.

We could all use a hype man like George Henry Lewes. “A

“A While recent events have provided a painful reminder of the very bad viruses that prey on us, Tom Ireland’s “The Good Virus” is a colorful redemption story for the oft-neglected yet incredibly abundant phage, and its potential for quelling the existential threat of antibiotic resistance, which scientists estimate might cause up to 10 million deaths per year by 2050. Ireland, an award-winning science journalist, approaches the subject of his first book with curiosity and passion, delivering a deft narrative that is rich and approachable.

While recent events have provided a painful reminder of the very bad viruses that prey on us, Tom Ireland’s “The Good Virus” is a colorful redemption story for the oft-neglected yet incredibly abundant phage, and its potential for quelling the existential threat of antibiotic resistance, which scientists estimate might cause up to 10 million deaths per year by 2050. Ireland, an award-winning science journalist, approaches the subject of his first book with curiosity and passion, delivering a deft narrative that is rich and approachable. It is well, at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest. Wheels that have crossed long, dusty distances with their mineral and vegetable burdens, sacks from the coalbins, barrels and baskets, handles and hafts for the carpenter’s tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth … The used surfaces of things, the wear that the hands give to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things—all lend a curious attractiveness to the reality of the world that should not be underprized.

It is well, at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest. Wheels that have crossed long, dusty distances with their mineral and vegetable burdens, sacks from the coalbins, barrels and baskets, handles and hafts for the carpenter’s tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth … The used surfaces of things, the wear that the hands give to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things—all lend a curious attractiveness to the reality of the world that should not be underprized.