Shelley Fan in Singularity Hub:

The components sound like the aftermath of a shopping and spa retreat: three AA batteries. Two electrical acupuncture needles. One plastic holder that’s usually attached to battery-powered fairy lights. But together they merge into a powerful stimulation device that uses household batteries to control gene expression in cells.

The idea seems wild, but a new study in Nature Metabolism this week showed that it’s possible. The team, led by Dr. Martin Fussenegger at ETH Zurich and the University of Basel in Switzerland, developed a system that uses direct-current electricity—in the form of batteries or portable battery banks—to turn on a gene in human cells in mice with a literal flip of a switch. To be clear, the battery pack can’t regulate in vivo human genes. For now, it only works for lab-made genes inserted into living cells. Yet the interface has already had an impact. In a proof-of-concept test, the scientists implanted genetically engineered human cells into mice with Type 1 diabetes. These cells are normally silent, but can pump out insulin when activated with an electrical zap.

The idea seems wild, but a new study in Nature Metabolism this week showed that it’s possible. The team, led by Dr. Martin Fussenegger at ETH Zurich and the University of Basel in Switzerland, developed a system that uses direct-current electricity—in the form of batteries or portable battery banks—to turn on a gene in human cells in mice with a literal flip of a switch. To be clear, the battery pack can’t regulate in vivo human genes. For now, it only works for lab-made genes inserted into living cells. Yet the interface has already had an impact. In a proof-of-concept test, the scientists implanted genetically engineered human cells into mice with Type 1 diabetes. These cells are normally silent, but can pump out insulin when activated with an electrical zap.

The team used acupuncture needles to deliver the trigger for 10 seconds a day, and the blood sugar levels in the mice returned to normal within a month. The rodents even regained the ability to manage blood sugar levels after a large meal without the need for external insulin, a normally difficult feat.

Called “electrogenetics,” these interfaces are still in their infancy. But the team is especially excited for their potential in wearables to directly guide therapeutics for metabolic and potentially other disorders. Because the setup requires very little power, three AA batteries could trigger a daily insulin shot for more than five years, they said. The study is the latest to connect the body’s analogue controls—gene expression—with digital and programmable software such as smartphone apps. The system is “a leap forward, representing the missing link that will enable wearables to control genes in the not-so-distant future,” said the team.

More here.

For over 100 years the cadaver, that unsung hero of murder mysteries, has been accommodating, gracious and generally on time. There is no other figure in crime who has proved more reliable. Since the murder mystery first gained popularity, there have been two world wars, multiple economic crises, dance crazes and moonshots, the advent of radio, cinema, television and the internet. Ideas of right and wrong have evolved, tastes have changed. But through it all, the cadaver has shown up without complaint to do its job. A clock-puncher of the highest order, if you will.

For over 100 years the cadaver, that unsung hero of murder mysteries, has been accommodating, gracious and generally on time. There is no other figure in crime who has proved more reliable. Since the murder mystery first gained popularity, there have been two world wars, multiple economic crises, dance crazes and moonshots, the advent of radio, cinema, television and the internet. Ideas of right and wrong have evolved, tastes have changed. But through it all, the cadaver has shown up without complaint to do its job. A clock-puncher of the highest order, if you will.

I

I It’s tempting to imagine memory as a videotape that stores and plays back the past just as it happened. But the workings of the mind are

It’s tempting to imagine memory as a videotape that stores and plays back the past just as it happened. But the workings of the mind are  Over the past few years, Korean reality TV has been a source of inspiration for my writing. Reading the subtitles is an amazing lesson in dialogue. The random casts of participants are a fun study of group dynamics. These shows allow me to witness tender, precarious moments between lovers and strangers. They prove that the mundane and dramatic often go hand in hand. Watching them, I’ve cried, laughed, and shouted at the screen. I’ve become more aware of how we are all living a life of scenes, surrounded by and involved in a seemingly never-ending narrative.

Over the past few years, Korean reality TV has been a source of inspiration for my writing. Reading the subtitles is an amazing lesson in dialogue. The random casts of participants are a fun study of group dynamics. These shows allow me to witness tender, precarious moments between lovers and strangers. They prove that the mundane and dramatic often go hand in hand. Watching them, I’ve cried, laughed, and shouted at the screen. I’ve become more aware of how we are all living a life of scenes, surrounded by and involved in a seemingly never-ending narrative. I

I  The California State Board of Education’s new math framework, adopted last month, has drawn intense public criticism. Most critics have focused on the framework’s overt political content or its aims to achieve “equity” by holding back advanced students, but there is an arguably even more fundamental problem: an approach to education called inquiry learning, which has virtually zero grounding in research. There is little in the framework that resembles real mathematical learning.

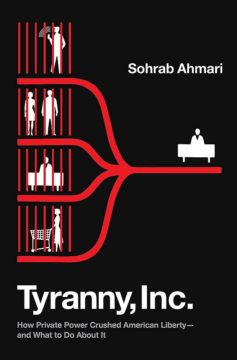

The California State Board of Education’s new math framework, adopted last month, has drawn intense public criticism. Most critics have focused on the framework’s overt political content or its aims to achieve “equity” by holding back advanced students, but there is an arguably even more fundamental problem: an approach to education called inquiry learning, which has virtually zero grounding in research. There is little in the framework that resembles real mathematical learning. Yascha Mounk: You have a really interesting new book called

Yascha Mounk: You have a really interesting new book called  Nearly every step of O’Connor’s career brought trouble. While making her debut album, 1987’s

Nearly every step of O’Connor’s career brought trouble. While making her debut album, 1987’s  T

T It must be a while ago now since

It must be a while ago now since  Stanford University scientists have invented a new kind of paint that can keep homes and other buildings cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter, significantly reducing energy use, costs, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Stanford University scientists have invented a new kind of paint that can keep homes and other buildings cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter, significantly reducing energy use, costs, and greenhouse gas emissions. L

L W

W