Jonathan Romney at The Current:

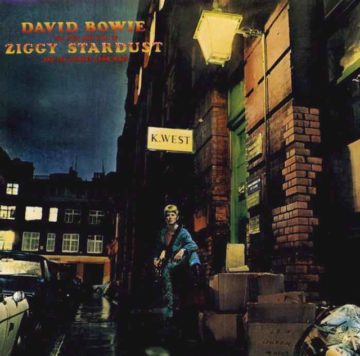

Right from the start, Brett Morgen’s Moonage Daydream (2022) catches us off guard. It begins with an epigraph musing on Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation that “God is dead,” then takes us into deep space and onto the surface of the moon. It then unleashes an image storm of rockets, robots, and star-gazers, and rapid-fire fragments of early silent cinema, 1920s science fiction, fifties cartoons, and sixties and seventies newsreel footage, before lingering on a close-up of glittery varnish on fingernails. The effect is dizzying, and Morgen has fittingly described the film, a tribute to the late David Bowie, as “an experiential documentary.” This is not a conventional account of a rock musician’s life and work. Neither a concert movie nor an information-laden career overview, it is instead a free-associative hybrid of pop history and imaginative extravaganza—impressionistic, eclectically allusive, and, above all, immersive.

Right from the start, Brett Morgen’s Moonage Daydream (2022) catches us off guard. It begins with an epigraph musing on Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation that “God is dead,” then takes us into deep space and onto the surface of the moon. It then unleashes an image storm of rockets, robots, and star-gazers, and rapid-fire fragments of early silent cinema, 1920s science fiction, fifties cartoons, and sixties and seventies newsreel footage, before lingering on a close-up of glittery varnish on fingernails. The effect is dizzying, and Morgen has fittingly described the film, a tribute to the late David Bowie, as “an experiential documentary.” This is not a conventional account of a rock musician’s life and work. Neither a concert movie nor an information-laden career overview, it is instead a free-associative hybrid of pop history and imaginative extravaganza—impressionistic, eclectically allusive, and, above all, immersive.

more here.

The word that comes to mind to describe all this—the light, the music, the sacred waters, the sacred garments—is “pilgrimage.” One rarely sees living writers treated with such reverence. “I am just a strange guy from the western part of Norway, from the rural part of Norway,” Fosse told me. He grew up a mixture of a communist and an anarchist, a “hippie” who loved playing the fiddle and reading in the countryside. He enrolled at the University of Bergen, where he studied comparative literature and started writing in Nynorsk, the written standard specific to the rural regions of the west. His first novel, “Red, Black,” was published in 1983, followed throughout the next three decades by “

The word that comes to mind to describe all this—the light, the music, the sacred waters, the sacred garments—is “pilgrimage.” One rarely sees living writers treated with such reverence. “I am just a strange guy from the western part of Norway, from the rural part of Norway,” Fosse told me. He grew up a mixture of a communist and an anarchist, a “hippie” who loved playing the fiddle and reading in the countryside. He enrolled at the University of Bergen, where he studied comparative literature and started writing in Nynorsk, the written standard specific to the rural regions of the west. His first novel, “Red, Black,” was published in 1983, followed throughout the next three decades by “ In more than 1,500 animal species, from crickets and sea urchins to bottlenose dolphins and bonobos, scientists have observed sexual encounters between members of the same sex. Some researchers have proposed that this behavior has existed

In more than 1,500 animal species, from crickets and sea urchins to bottlenose dolphins and bonobos, scientists have observed sexual encounters between members of the same sex. Some researchers have proposed that this behavior has existed  Using a host of high-tech tools to simulate brain development in a lab dish, Stanford University researchers have

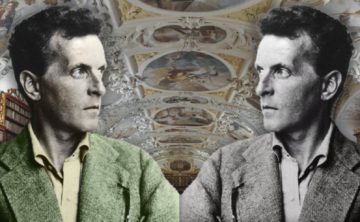

Using a host of high-tech tools to simulate brain development in a lab dish, Stanford University researchers have  Few philosophers have given rise to an entire movement, far fewer to two. Along with Heidegger, Wittgenstein counts among this select number in the 20th Century. Wittgenstein capped his early career with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a dense cryptic book whose truth he found “unassailable and definitive” in finding “on all essential points, the final solution of the problems” (T Preface)–until he came back years later to assail its solutions. He returned to give not just different solutions, but an entirely different take on the nature of knowledge, reality, and what philosophical views about such matters must be like. These two phases of his thought shaped much of roughly the first half of analytic philosophy’s history. The Tractatus brings Frege, Russell, and Moore’s logicism to its culmination and inspired the Vienna Circle. His later work, generally represented by the posthumous Philosophical Investigations, is a foundational work of the ordinary language philosophy practiced by Austin and Ryle and, despite his personal hostility to naturalism, contains elements that pushed analytic thought in that direction where Quine and others then took over. One of the central topics Wittgenstein changed his mind about was on the question of realism – whether we can know the world as it really is and whether our language can map onto reality.

Few philosophers have given rise to an entire movement, far fewer to two. Along with Heidegger, Wittgenstein counts among this select number in the 20th Century. Wittgenstein capped his early career with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a dense cryptic book whose truth he found “unassailable and definitive” in finding “on all essential points, the final solution of the problems” (T Preface)–until he came back years later to assail its solutions. He returned to give not just different solutions, but an entirely different take on the nature of knowledge, reality, and what philosophical views about such matters must be like. These two phases of his thought shaped much of roughly the first half of analytic philosophy’s history. The Tractatus brings Frege, Russell, and Moore’s logicism to its culmination and inspired the Vienna Circle. His later work, generally represented by the posthumous Philosophical Investigations, is a foundational work of the ordinary language philosophy practiced by Austin and Ryle and, despite his personal hostility to naturalism, contains elements that pushed analytic thought in that direction where Quine and others then took over. One of the central topics Wittgenstein changed his mind about was on the question of realism – whether we can know the world as it really is and whether our language can map onto reality. Our planet and its environment are in bad shape, in all sorts of ways. Those of us who want to improve the situation face a dilemma. On the one hand, we have to be forceful and clear-headed about how the bad the situation actually is. On the other, we don’t want to give the impression that things are so bad that it’s hopeless. That could — and, empirically, does — give people the impression that there’s no point in working to make things better. Hannah Ritchie is an environmental researcher at Our World in Data who wants to thread this needle: things are bad, but there are ways we can work to make them better.

Our planet and its environment are in bad shape, in all sorts of ways. Those of us who want to improve the situation face a dilemma. On the one hand, we have to be forceful and clear-headed about how the bad the situation actually is. On the other, we don’t want to give the impression that things are so bad that it’s hopeless. That could — and, empirically, does — give people the impression that there’s no point in working to make things better. Hannah Ritchie is an environmental researcher at Our World in Data who wants to thread this needle: things are bad, but there are ways we can work to make them better. The recent death of Milan Kundera brought me back to the fall of 2006, to the aftermath of what we Israelis call the Second Lebanon War, when I first read his work.

The recent death of Milan Kundera brought me back to the fall of 2006, to the aftermath of what we Israelis call the Second Lebanon War, when I first read his work. As the owner of fifty lava lamps, I felt validated when I found out about Cloudflare’s wall. I bought all the lamps within a six-month span I now refer to as my “lava period.” It started when I broke my lava lamp of eight years by leaving it on for two weeks. The lamp had survived the dumpster I found it in, and two cross-country moves, but it couldn’t endure its own heat. Many things went wrong at once: the wax (the “lava,” the substance that moves) started sticking to the glass, the liquid lost its color, and the spring that sat at the base of the globe broke into pieces. Little bits of metal bobbed at the surface, as though drowning and reaching up for help.

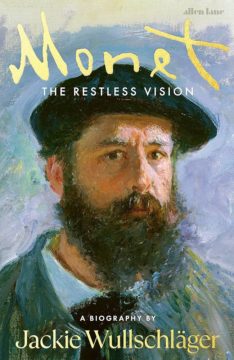

As the owner of fifty lava lamps, I felt validated when I found out about Cloudflare’s wall. I bought all the lamps within a six-month span I now refer to as my “lava period.” It started when I broke my lava lamp of eight years by leaving it on for two weeks. The lamp had survived the dumpster I found it in, and two cross-country moves, but it couldn’t endure its own heat. Many things went wrong at once: the wax (the “lava,” the substance that moves) started sticking to the glass, the liquid lost its color, and the spring that sat at the base of the globe broke into pieces. Little bits of metal bobbed at the surface, as though drowning and reaching up for help. You long for sublime artists to be sublime people. Or, if they’re bad, to be magnificently so. Possessing ‘a vanity born of supreme egoism’, Claude Monet ‘believed his art conferred a right to good living’ and that ‘his welfare must be … the immediate concern of others’, writes Jackie Wullschläger, chief art critic of the Financial Times. With great honesty, Wullschläger records her subject’s wearisome scrounging letters and his propensity for petty and often pointless mendacity. At the end of his life, when he was earning millions, he at last became generous with money. We chafe at his domestic tyranny, but that was par for the course at the time. Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner, and we’d forgive Monet a lot more than this for his divine art.

You long for sublime artists to be sublime people. Or, if they’re bad, to be magnificently so. Possessing ‘a vanity born of supreme egoism’, Claude Monet ‘believed his art conferred a right to good living’ and that ‘his welfare must be … the immediate concern of others’, writes Jackie Wullschläger, chief art critic of the Financial Times. With great honesty, Wullschläger records her subject’s wearisome scrounging letters and his propensity for petty and often pointless mendacity. At the end of his life, when he was earning millions, he at last became generous with money. We chafe at his domestic tyranny, but that was par for the course at the time. Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner, and we’d forgive Monet a lot more than this for his divine art. Oversharing in conversation is nothing new. Throughout thousands of years of social interaction, people have divulged certain secrets, vulnerabilities, and desires to perhaps the wrong listener, with results ranging from mild embarrassment to shattered reputations. Thanks to social media, the ability to make these confessions to a potentially much wider audience is easier than ever.

Oversharing in conversation is nothing new. Throughout thousands of years of social interaction, people have divulged certain secrets, vulnerabilities, and desires to perhaps the wrong listener, with results ranging from mild embarrassment to shattered reputations. Thanks to social media, the ability to make these confessions to a potentially much wider audience is easier than ever. RNA-based vaccines were the

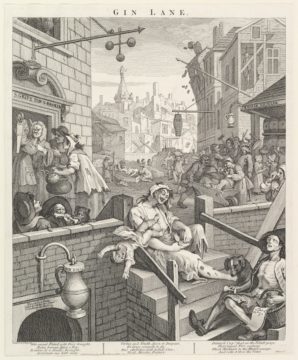

RNA-based vaccines were the  In 1751, the engraver and satirist William Hogarth created Gin Lane, his celebrated visual retrospective about the devastating effects of this newfangled spirit on the lives of London’s poor. The print, a companion piece to Beer Street, offers a harrowing panorama of poverty, addiction, insanity, violence, infanticide, and suicide; the only people and institutions who thrive amongst the mayhem and despair are an undertaker, “Gripe” the pawnbroker, and the two purveyors of the “deadly draught”: a cellar gin shop and “Kilman” the distiller. In the words of Hogarth’s most recent biographer, Gin Lane’s “racked scene of dissolution

In 1751, the engraver and satirist William Hogarth created Gin Lane, his celebrated visual retrospective about the devastating effects of this newfangled spirit on the lives of London’s poor. The print, a companion piece to Beer Street, offers a harrowing panorama of poverty, addiction, insanity, violence, infanticide, and suicide; the only people and institutions who thrive amongst the mayhem and despair are an undertaker, “Gripe” the pawnbroker, and the two purveyors of the “deadly draught”: a cellar gin shop and “Kilman” the distiller. In the words of Hogarth’s most recent biographer, Gin Lane’s “racked scene of dissolution  One summer’s day in 1976, the philosopher

One summer’s day in 1976, the philosopher