Amy Kapczynski, Reshma Ramachandran and Christopher Morten in Boston Review:

Amy Kapczynski, Reshma Ramachandran and Christopher Morten in Boston Review:

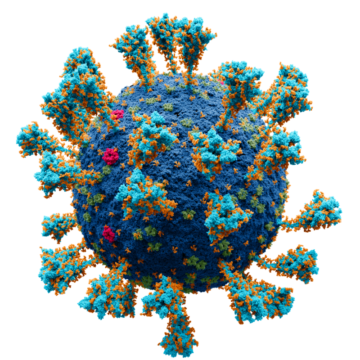

There have been no higher-stakes public investments recently than those the federal government made in biomedical research and production to make COVID-19 vaccines. Many commentators, conservatives and progressives alike, have seen the program that directed these investments, Operation Warp Speed (OWS), as a key example of how the government can enact new industrial policy—the deliberate attempt to shape different sectors of the economy to meet public aims. David Adler, for example, calls OWS “a triumph and validation of industrial policy,” concluding that the initiative “illustrates best practices in program design, as well as in government contracting” and should be a model for efforts to implement industrial strategy more broadly.

We think this view is seriously misguided. There is nothing new about industrial policy if it simply means public investments that yield vast benefits and outsized control for the private sector and comparatively little for the public. As historian Brent Cebul describes in his new book, Illusions of Progress, “supply-side liberalism”—a pattern of governance that directs federal money toward public aims but cedes critical aspects of policy, rules, and authority to the private sector—has a long history in the United States. In the late New Deal, ambitious federal spending programs like the Works Progress Administration gave significant control to local actors in order to overcome opposition of racist demagogues and business elites. This decentralized, deferential administrative model had staying power because it compensated for a lack of state capacity—and in turn, it helped ensure that no such capacity would be built. Cebul traces this template through the design of the postwar Federal Housing Administration and urban renewal into the 1980s and ’90s, when public-private partnerships and market-centered solutions became predominant during the Carter, Reagan, George H. Bush, and Clinton administrations.

The case of COVID-19 vaccines extends this pattern of political economy.

More here.

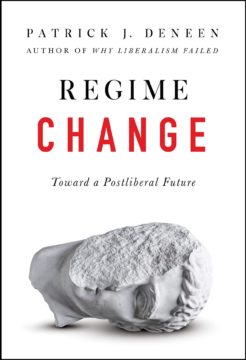

Jeffrey C. Isaac in LA Review of Books:

Jeffrey C. Isaac in LA Review of Books: Alvin Camba in Phenomenal World:

Alvin Camba in Phenomenal World: William Callison in Sidecar:

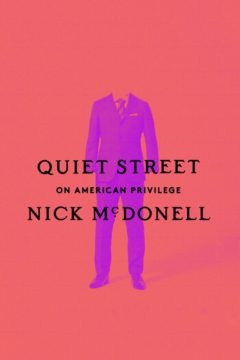

William Callison in Sidecar: IN HIS 1980 ESSAY ON THE AMERICAN SCENE, “Within the Context of No Context,” George W. S. Trow supplies an anecdote from Harvard in the early 1960s. During an art history class on the Dutch masters, a Black student described Rembrandt as “‘belonging’ to the white students in the room.” The white students totally agreed with this. “They acknowledged that they were at one with Rembrandt,” Trow writes. “They acknowledged their dominance. They offered to discuss, at any length, their inherited power to oppress.”

IN HIS 1980 ESSAY ON THE AMERICAN SCENE, “Within the Context of No Context,” George W. S. Trow supplies an anecdote from Harvard in the early 1960s. During an art history class on the Dutch masters, a Black student described Rembrandt as “‘belonging’ to the white students in the room.” The white students totally agreed with this. “They acknowledged that they were at one with Rembrandt,” Trow writes. “They acknowledged their dominance. They offered to discuss, at any length, their inherited power to oppress.” Not long ago our mother died, or at least her body did—the rest of her remained obstinately alive. She took a considerable time to die and outlasted the nurses’ predictions by many days, so that those of us who had been summoned to her bedside had to depart and return to our lives.

Not long ago our mother died, or at least her body did—the rest of her remained obstinately alive. She took a considerable time to die and outlasted the nurses’ predictions by many days, so that those of us who had been summoned to her bedside had to depart and return to our lives. Picture this: the setting sun paints a cornfield in dazzling hues of amber and gold. Thousands of corn stalks, heavy with cobs and rustling leaves, tower over everyone—kids running though corn mazes; farmers examining their crops; and robots whizzing by as they gently pluck ripe, sweet ears for the fall harvest.

Picture this: the setting sun paints a cornfield in dazzling hues of amber and gold. Thousands of corn stalks, heavy with cobs and rustling leaves, tower over everyone—kids running though corn mazes; farmers examining their crops; and robots whizzing by as they gently pluck ripe, sweet ears for the fall harvest. John Waters was kicked out of NYU film school for smoking marijuana. Even that incubator for original filmmakers couldn’t handle him. Now, among people I know, announcing yourself as a graduate of NYU film school is a shorthand for being an uppity, social-climbing brat (I should know, I’m one of them). It’s so much cooler to be John Waters. He’s a degenerate and an iconoclast, making even the most daring artists look like uninspired conformists. In fact, I don’t know anyone who dislikes John Waters. If I did, I would think it was an easy tell that they were boring and had bad sex.

John Waters was kicked out of NYU film school for smoking marijuana. Even that incubator for original filmmakers couldn’t handle him. Now, among people I know, announcing yourself as a graduate of NYU film school is a shorthand for being an uppity, social-climbing brat (I should know, I’m one of them). It’s so much cooler to be John Waters. He’s a degenerate and an iconoclast, making even the most daring artists look like uninspired conformists. In fact, I don’t know anyone who dislikes John Waters. If I did, I would think it was an easy tell that they were boring and had bad sex. A string of job postings from high-profile training data companies, such as

A string of job postings from high-profile training data companies, such as  Deep in Pakistan’s countryside, Sindhi Chhokri and her teenage brother Toxic Sufi are raising a few eyebrows.

Deep in Pakistan’s countryside, Sindhi Chhokri and her teenage brother Toxic Sufi are raising a few eyebrows. In 1978, Kathy Kleiner was asleep in her bed at the Chi Omega sorority house at Florida State University when serial killer Ted Bundy entered through an unlocked door. After attacking two of her sorority sisters, Bundy found Kathy’s door also unlocked.

In 1978, Kathy Kleiner was asleep in her bed at the Chi Omega sorority house at Florida State University when serial killer Ted Bundy entered through an unlocked door. After attacking two of her sorority sisters, Bundy found Kathy’s door also unlocked.  We asked young scientists this question: If you could introduce any two scientists, regardless of where and when they lived, whom would you choose, and how would their collaboration change the course of history? Read a selection of the responses here. Follow NextGen Voices on social media with hashtag #NextGenSci.

We asked young scientists this question: If you could introduce any two scientists, regardless of where and when they lived, whom would you choose, and how would their collaboration change the course of history? Read a selection of the responses here. Follow NextGen Voices on social media with hashtag #NextGenSci.

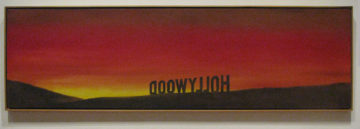

In a past life, he was an arsonist. A bold accusation, I realize, but nobody makes that many paintings, drawings, and photographs of fire without some buried lust for the real deal. By the time I left “Ed Ruscha / Now Then,” an XXL retrospective at moma comprising some two hundred works produced between the Eisenhower years and the present, I had lost count of the burning things, which are as lowbrow as a diner and as la-di-da as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The title of Ruscha’s 1964 photo series, “Various Small Fires and Milk,” could have been, minus the milk, a reasonable title for the exhibition itself, if he hadn’t painted various large ones, too.

In a past life, he was an arsonist. A bold accusation, I realize, but nobody makes that many paintings, drawings, and photographs of fire without some buried lust for the real deal. By the time I left “Ed Ruscha / Now Then,” an XXL retrospective at moma comprising some two hundred works produced between the Eisenhower years and the present, I had lost count of the burning things, which are as lowbrow as a diner and as la-di-da as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The title of Ruscha’s 1964 photo series, “Various Small Fires and Milk,” could have been, minus the milk, a reasonable title for the exhibition itself, if he hadn’t painted various large ones, too.

A famous

A famous  Right now, many forms of knowledge production seem to be facing their end. The crisis of the humanities has reached a tipping point of financial and popular disinvestment, while technological advances such as new artificial intelligence programmes may outstrip human ingenuity. As news outlets disappear, extreme political movements question the concept of objectivity and the scientific process. Many of our systems for producing and certifying knowledge have ended or are ending.

Right now, many forms of knowledge production seem to be facing their end. The crisis of the humanities has reached a tipping point of financial and popular disinvestment, while technological advances such as new artificial intelligence programmes may outstrip human ingenuity. As news outlets disappear, extreme political movements question the concept of objectivity and the scientific process. Many of our systems for producing and certifying knowledge have ended or are ending.