Elie Dolgin in Nature:

RNA-based vaccines were the heroes of the COVID-19 pandemic. They set records for the highest-grossing drug launches in history, and their development was recognized in this year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. But it was long known that this technology had a key shortcoming: RNA, in its usual linear form, is short-lived. Within hours, enzymes in cells descend on the molecule, chewing it to pieces. RNA’s fleeting nature isn’t a big problem for a vaccine: it needs to encode proteins only for a short time to trigger an immune response. But for most therapeutic applications, it would be much better to have RNA that could stick around for longer.

RNA-based vaccines were the heroes of the COVID-19 pandemic. They set records for the highest-grossing drug launches in history, and their development was recognized in this year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. But it was long known that this technology had a key shortcoming: RNA, in its usual linear form, is short-lived. Within hours, enzymes in cells descend on the molecule, chewing it to pieces. RNA’s fleeting nature isn’t a big problem for a vaccine: it needs to encode proteins only for a short time to trigger an immune response. But for most therapeutic applications, it would be much better to have RNA that could stick around for longer.

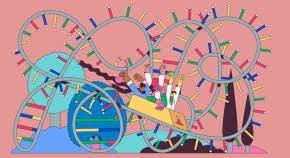

That’s where circular RNAs, or circRNAs, come in. Tie the ends of an RNA transcript together, and many RNA-munching enzymes have nothing to sink their teeth into. As a ring, RNA gains stability and longevity that, in theory, could increase its therapeutic potential, even at low dose levels. “With a single delivery, you can get quite durable protein production,” says Howard Chang, a molecular geneticist at Stanford University School of Medicine in California and a scientific co-founder of Orbital Therapeutics in Cambridge, Massachusetts — one of the dozen or more biotechnology firms that are now pursuing therapeutics based on engineered circular RNA. These biotech firms have collectively raised well in excess of US$1 billion in venture-capital funding over the past three years, and many big pharmaceutical companies are now dabbling in the technology as well. They are driven by the belief that whatever linear RNA can do, its more resilient circular counterpart can do better.

More here.