Sue Prideaux at Literary Review:

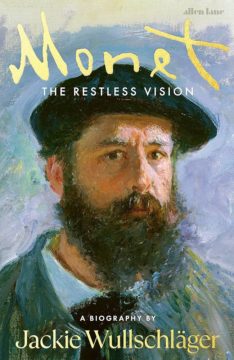

You long for sublime artists to be sublime people. Or, if they’re bad, to be magnificently so. Possessing ‘a vanity born of supreme egoism’, Claude Monet ‘believed his art conferred a right to good living’ and that ‘his welfare must be … the immediate concern of others’, writes Jackie Wullschläger, chief art critic of the Financial Times. With great honesty, Wullschläger records her subject’s wearisome scrounging letters and his propensity for petty and often pointless mendacity. At the end of his life, when he was earning millions, he at last became generous with money. We chafe at his domestic tyranny, but that was par for the course at the time. Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner, and we’d forgive Monet a lot more than this for his divine art.

You long for sublime artists to be sublime people. Or, if they’re bad, to be magnificently so. Possessing ‘a vanity born of supreme egoism’, Claude Monet ‘believed his art conferred a right to good living’ and that ‘his welfare must be … the immediate concern of others’, writes Jackie Wullschläger, chief art critic of the Financial Times. With great honesty, Wullschläger records her subject’s wearisome scrounging letters and his propensity for petty and often pointless mendacity. At the end of his life, when he was earning millions, he at last became generous with money. We chafe at his domestic tyranny, but that was par for the course at the time. Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner, and we’d forgive Monet a lot more than this for his divine art.

Born in 1840, the petted son of a prosperous family who disdained the arts, Monet grew up in Le Havre.

more here.