Sam Sweet at The Baffler:

Gardena’s poker clubs were the product of a legal loophole in California’s 1872 gaming legislation, which outlawed gambling but made an exception for the specific style of draw poker. (Draw poker being the preferred game among nineteenth-century legislators.) No California localities abided poker except Gardena, where a savvy investor named Ernest Primm exerted enough pressure to earn a permit for his first club in 1936. By the 1960s, the Gardena clubs numbered six: the Rainbow, the Monterey, the Normandie, the Horseshoe, the Gardena, and the El Dorado.

With its free meals and cocktails and stage shows, Vegas catered to losers. Gardena catered to regulars. It offered them nothing but poker. Instead of taking a percentage, the clubs made money by selling time. Every half hour, a red light would appear on the clock and players would hand a few dollars in chips to roving “chip girls” who deposited the rent into their sagging aprons.

more here.

The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges lost his vision—what he called his “reader’s and writer’s sight”—around the same time that he became the director of the National Library of Argentina. This put him in charge of nearly a million books, he observed, at the very moment he could no longer read them.

The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges lost his vision—what he called his “reader’s and writer’s sight”—around the same time that he became the director of the National Library of Argentina. This put him in charge of nearly a million books, he observed, at the very moment he could no longer read them. If you feed America’s most important legal document—the

If you feed America’s most important legal document—the  In 1950, Eleanor Roosevelt, serving as the first Chairperson of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, was involved in a bitter

In 1950, Eleanor Roosevelt, serving as the first Chairperson of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, was involved in a bitter  The Quick and the Dead, which is not set in Florida but in the West, is one of the weirdest, funniest, darkest novels you’ll ever read. It lost the 2001 Pulitzer Prize to The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, thus fulfilling the promise of Luke 4:24. Williams’s new novel, Harrow, is Quick’s spiritual successor, perhaps even sequel, taking up that novel’s concerns and amplifying them by the full twenty years it took her to write it. Harrow reminds me very much of Denis Johnson’s Fiskadoro and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, but, with apologies to the boys, it’s better than both of their novels put together. Harrow belongs at the front of the pack of recent climate fiction, even as it refuses the basic premise (human survival is important) and the sentimental rays of hope (another world is possible!) that are the hallmarks of the genre. This novel doesn’t care who you vote for or if you recycle. It’s not bullish on green tech jobs or sustainable meat. It would leave Steven “Things Are Getting Better” Pinker and Matthew “One Billion Americans” Yglesias writhing in shame if guys like them were capable of reading novels or feeling shame. Harrow is a crabby, craggy, comfortless, arid, erudite, obtuse, perfect novel, a singular entry in a singular body of work by an artist of uncompromised originality and vision. For all of its fragmentation and deliberate strategies of estrangement, Harrow feels coherent and complete, like a single long-form thought or a religious epiphany. It’s also funny as hell.

The Quick and the Dead, which is not set in Florida but in the West, is one of the weirdest, funniest, darkest novels you’ll ever read. It lost the 2001 Pulitzer Prize to The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, thus fulfilling the promise of Luke 4:24. Williams’s new novel, Harrow, is Quick’s spiritual successor, perhaps even sequel, taking up that novel’s concerns and amplifying them by the full twenty years it took her to write it. Harrow reminds me very much of Denis Johnson’s Fiskadoro and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, but, with apologies to the boys, it’s better than both of their novels put together. Harrow belongs at the front of the pack of recent climate fiction, even as it refuses the basic premise (human survival is important) and the sentimental rays of hope (another world is possible!) that are the hallmarks of the genre. This novel doesn’t care who you vote for or if you recycle. It’s not bullish on green tech jobs or sustainable meat. It would leave Steven “Things Are Getting Better” Pinker and Matthew “One Billion Americans” Yglesias writhing in shame if guys like them were capable of reading novels or feeling shame. Harrow is a crabby, craggy, comfortless, arid, erudite, obtuse, perfect novel, a singular entry in a singular body of work by an artist of uncompromised originality and vision. For all of its fragmentation and deliberate strategies of estrangement, Harrow feels coherent and complete, like a single long-form thought or a religious epiphany. It’s also funny as hell. After hundreds of hours listening to thousands of wolves for my PhD, the difference between howls was obvious. The voice of a Russian wolf was nothing like that of a Canadian, and a jackal was so utterly different again that it was like listening to Farsi and French. I believed that there must be geographic and subspecies distinctions. Other researchers had made this proposition before, but no one had put together a large enough collection of howls to test it properly. A few years later, my degree finished, I told my Dracula story to the zoologist Arik Kershenbaum at the University of Cambridge. He promptly suggested we explore how attuned to wolves I really am. Are there differences between canid species and subspecies and, if so, could these reflect diverging cultures?

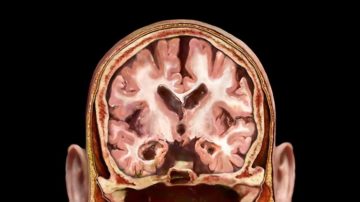

After hundreds of hours listening to thousands of wolves for my PhD, the difference between howls was obvious. The voice of a Russian wolf was nothing like that of a Canadian, and a jackal was so utterly different again that it was like listening to Farsi and French. I believed that there must be geographic and subspecies distinctions. Other researchers had made this proposition before, but no one had put together a large enough collection of howls to test it properly. A few years later, my degree finished, I told my Dracula story to the zoologist Arik Kershenbaum at the University of Cambridge. He promptly suggested we explore how attuned to wolves I really am. Are there differences between canid species and subspecies and, if so, could these reflect diverging cultures? A study that followed thousands of people over 25 years has identified proteins linked to the development of dementia if their levels are unbalanced during middle age. The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine on 19 July

A study that followed thousands of people over 25 years has identified proteins linked to the development of dementia if their levels are unbalanced during middle age. The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine on 19 July Life finds a way.

Life finds a way. Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.