Month: July 2023

Randy Meisner (1946 – 2023) Musician, Co-Founder Of The Eagles

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JvTuW-MX1Mk&ab_channel=CIMACulturalTijuana

Homage

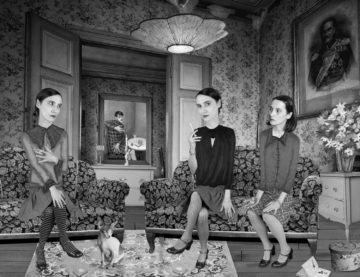

Cornelia Hediger in lensculture:

This series of handmade photomontages was inspired by figurative master paintings created throughout art history—important moments in the western canon. My love for the particular presence of master paintings, combined with my own interest in photography, provided a starting point from which to explore. I then created reinventions—re-masterings—working through my personal sensitivity and engagements as an artist. Photomontage allows me to translate these paintings into new environments.

This series of handmade photomontages was inspired by figurative master paintings created throughout art history—important moments in the western canon. My love for the particular presence of master paintings, combined with my own interest in photography, provided a starting point from which to explore. I then created reinventions—re-masterings—working through my personal sensitivity and engagements as an artist. Photomontage allows me to translate these paintings into new environments.

For me, this is an act of translation. While I use contemporary technologies, I endeavor to maintain the tactile qualities and varied dimensionalities that drew me to the objects in the first place. This series attempts to capture the ghosts of occidental imaginary, always partial and illusive, while proposing new visual languages around these established masterpieces. Homage is a meditation on the passage of time. It is a reflection on where I am, as an artist, in the 21st century, ever-influenced by the past and by my heritage.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Smile

When I see a black man smiling

like that, nodding and smiling

with both hands visible, mouthing

“Yes, Officer,” across the street,

I think of my father, who taught us

the words “cooperate,” “officer,”

to memorize badge numbers,

who has seen black men shot at

from behind in the warm months north.

And I think of the fine line—

hairline, eyelash, fingernail paring—

the whisper that separates

obsequious from safe. Armstrong,

Johnson, Robinson, Mays.

A woman with a yellow head

of cotton-candy hair stumbles out

of a bar at after lunch-time

clutching a black man’s arm as if

for her life. And the brother

smiles, and his eyes are flint

as he watches all sides of the street.

by Elizabeth Alexander

from What Saves Us— Poems of

. . .. . Empathy and Outrage in the Age of Trump

Edited by Martín Espada

Curbstone Books, 2019

The Dutiful Wife

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

THERE IS, EASILY FOUND on the internet, a photograph of the writer Kingsley Amis relaxing on a beach with his back to the camera. Written in lipstick on his back are the words “1 fat Englishman. I fuck anything.” The words are the handiwork of his then wife Hilly, who had learned that her husband was having an affair with fashion model Elizabeth Jane Howard. Howard would eventually become the writer’s wife, the two of them having fallen in love during the inaugural Cheltenham literary festival that Amis had attended (and Howard had directed).

THERE IS, EASILY FOUND on the internet, a photograph of the writer Kingsley Amis relaxing on a beach with his back to the camera. Written in lipstick on his back are the words “1 fat Englishman. I fuck anything.” The words are the handiwork of his then wife Hilly, who had learned that her husband was having an affair with fashion model Elizabeth Jane Howard. Howard would eventually become the writer’s wife, the two of them having fallen in love during the inaugural Cheltenham literary festival that Amis had attended (and Howard had directed).

Having won the spot beside this literary genius was a dubious blessing. Howard, who had written three novels of her own before ever meeting the author who made his reputation with the publication of Lucky Jim in 1954 (and who in 1963 published One Fat Englishman), found herself running a large household revolving around the lone star of Amis. She stopped writing, took to cooking elaborate meals, juggling the schedule of Amis’s two sons to whom she was stepmother and a thousand other necessary tasks. As recounted in Carmela Ciuraru’s recent book Lives of the Wives: Five Literary Marriages, Howard was often so very tired that she would fall asleep sitting upright in a chair in the evening. With this capable woman at his side, Amis continued his writing career having changed out the wife he had procured at Oxford for a prettier new model.

More here.

Artificial intelligence and jobs: Evidence from Europe

Stefania Albanesi, Antonio Dias da Silva, Juan Francisco Jimeno, Ana Lamo and Alena Wabitsch in VoxEU:

AI breakthroughs have come in many fields. These include advancements in robotics, supervised and unsupervised learning, natural language processing, machine translation, or image recognition, among many other activities that enable automation of human labour in non-routine tasks, both in manufacturing but also services (e.g. medical advice or writing code). Artificial Intelligence is thus a general-purpose technology that could automate work in virtually every occupation. It stands in contrast to other technologies such as computerisation and industrial robotics which enable automation in a limited set of tasks by implementing manually-specified rules.

The existing empirical evidence on the overall effect of AI-enabled technologies on employment and wages is still evolving. For example, both Felten et al. (2019) and Acemoglu et al. (2022) conclude that occupations more exposed to AI experience no visible impact on employment. However, Acemoglu et al. (2022) find that AI-exposed establishments reduced non-AI and overall hiring, implying that AI is substituting human labour in a subset of tasks, while new tasks are created. Moreover, Felten et al. (2019) find that occupations impacted by AI experience a small but positive change in wages. On a different note, Webb (2020) argues that AI-enabled technologies are likely to affect high-skilled workers more, in contrast with software or robots. This literature focused mostly on the United States.

A recent Vox column (Ilzetzki and Jain 2023) discusses survey results from a panel of experts about the potential impact of AI on employment in a number of high-income countries. Most of the panel members believed that AI is unlikely to affect employment rates over the coming decade.

More here.

Pirates + Madagascar = Egalitarian Utopia? On David Graeber’s “Pirate Enlightenment, or The Real Libertalia”

Edward Carver in LA Review of Books:

WHEN HE died unexpectedly in 2020, American anthropologist and left-wing activist David Graeber was best known for his 2011 book Debt: The First 5,000 Years, a revisionist history of money, and his involvement in Occupy Wall Street. He helped coin the catchphrase “We are the 99 percent.”

But before he became a swashbuckling public intellectual, his work focused on Madagascar, where he did doctoral research on the legacy of slavery in a highlands village. In his posthumous new book, Pirate Enlightenment, or The Real Libertalia, he returns to the subject of Madagascar to tell a story that challenges Eurocentric ideas about the origins of the Enlightenment.

Pirate Enlightenment was first published in French in 2019. The publishing house that released it, Libertalia, is in fact named after a pirate utopia in Madagascar that was depicted in an English-language book in the 1720s but probably didn’t exist. Graeber is interested in the legend only insofar as it indicates the kind of political stories that were circulating in European coffeehouses. He regards it as a European fantasy, in which the Malagasy act only as antagonists to the utopians in the tale. The “Real Libertalia” of Graeber’s book is, in contrast, about the political arrangements of the Malagasy.

This builds on Graeber’s other work, including “There Never Was a West, or Democracy Emerges from the Spaces In Between,” a 2007 essay in which he argues that the ideas of freedom, democracy, and equality are not principally Western. In The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021), he and co-author David Wengrow, an archaeologist, dig up evidence that many complex societies existed without much hierarchy and that Enlightenment conceptions of human liberation flowed from many ancient and Indigenous traditions.

More here.

Fragile Democracies

Poornima Paidipaty interviews Pranab Bardhan in Phenomenal World:

Poornima Paidipaty interviews Pranab Bardhan in Phenomenal World:

POORNIMA PAIDIPATY: A World of Insecurity (Havard, 2022) covers a wide range of topics, from current economic inequality to the rise of populism and the importance of renewing institutions of social democracy across the globe. Maybe you can start by telling us about the inspiration behind the book—as a writer, what motivated you to piece all of this material together?

PRANAB BARDHAN: As a political economist, I’ve noticed that politics in many countries I’m interested in, both rich and poor, has been moving rightward (the major exception being in Latin America, but even there, leftwing victories have been fragile). I was interested in understanding this global shift. Everyone talks about the rich countries—Trump, Johnson, LePen, Meloni, the Sweden Democrats, among many others. Developing countries get less attention. In my study, I look at three developing countries: India, Turkey, and Brazil.

Existing work on the rise of the right revolves around the question of inequality—even in countries where it’s not rising, it is already very high. But again, much of this work is focused on Western Europe and the US, and I was interested in broadening this scope. Despite having worked quite a lot on inequality as an economist, I had a sense that this was not the full story. In particular, I felt that it doesn’t answer an essential question: Why are working people rallying under the banner of multi-millionaires? This is particularly confounding given that these billionaires, once they come to power, almost inevitably reduce taxes on the rich and weaken restrictions on the financial and corporate sector.

More here.

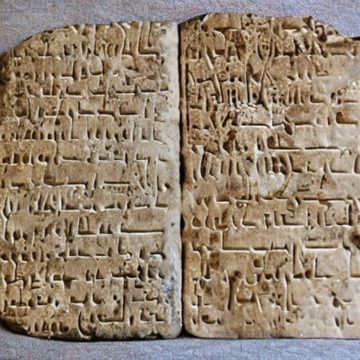

Poet of impermanence

Sophus Helle in Aeon:

Sophus Helle in Aeon:

About 4,200 years ago, the area we now call southern Iraq was rocked by revolts. The once-independent Sumerian city states had been brought under one rule by the legendary king Sargon of Akkad. Over the course of what modern historians call the Old Akkadian period, the reign of Sargon and his successors reshaped the newly conquered cities in countless ways: old nobles were demoted and new men brought to power, old enemies were defeated and new standards of statecraft imposed. The Sumerian world grew much bigger and richer, but also more unstable. Discontent with the new empire festered, provoking a steady stream of uprisings as the cities attempted to regain their independence.

One such revolt is depicted in a fascinating poem known as ‘The Exaltation of Inana’. Besides being a poetic masterpiece in its own right, ‘The Exaltation’ bears the distinction of being the first known work of literature that was attributed to an author whom we can identify in the historical record, rather than to an anonymous tradition or a fictional narrator. The narrator of the poem is Enheduana, the high priestess of the city of Ur and the daughter of Sargon. According to ‘The Exaltation’, she was cast into exile by one of the many revolts that plagued the Old Akkadian Empire.

More here.

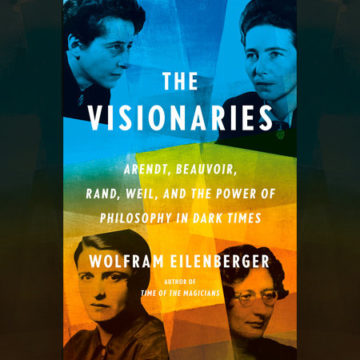

Ayn Rand, Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir and Simone Weil

Caroline Moorehead at The Guardian:

In the summer of 1933, four women, all in their 20s, were busy contemplating the meaning of their own existence and the importance of others to it. The word existentialism had not yet been invented, but the quartet were intrigued by the idea of finding a new philosophy, using their own intelligence to change themselves and the world, while working out how the individual and the collective played into the malaise of modern times. Over the next decade, as Wolfram Eilenberger writes, they all crossed paths intellectually, sometimes agreeing, more often not, though it seems that they never actually met.

In the summer of 1933, four women, all in their 20s, were busy contemplating the meaning of their own existence and the importance of others to it. The word existentialism had not yet been invented, but the quartet were intrigued by the idea of finding a new philosophy, using their own intelligence to change themselves and the world, while working out how the individual and the collective played into the malaise of modern times. Over the next decade, as Wolfram Eilenberger writes, they all crossed paths intellectually, sometimes agreeing, more often not, though it seems that they never actually met.

The eldest was an uncompromising and astute 28-year-old Russian who had got herself to Hollywood and changed her name from Alisa Rosenbaum to Ayn Rand. Through screenplays and fiction she set out to convey what she saw as the struggle for the autonomy of the soul, with “enlightened egoism” as her new vision for the world. Thus Spoke Zarathustra became “something like her house bible” and phrases such as “Nietzsche and I think …” peppered her philosophical notes.

more here.

Time of the Magicians

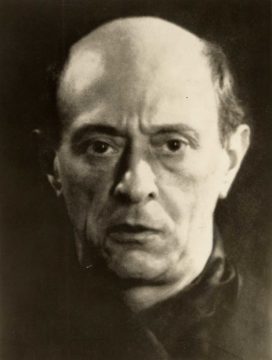

The Music of Arnold Schoenberg

John Adams at the New York Times:

In 1955 Henry Pleasants, a critic of both popular and classical music, issued a cranky screed of a book, “The Agony of Modern Music,” which opened with the implacable verdict that “serious music is a dead art.” Pleasants’s thesis was that the traditional forms of classical music — opera, oratorio, orchestral and chamber music, all constructions of a bygone era — no longer related to the experience of our modern lives. Composers had lost touch with the currents of popular taste, and popular music, with its vitality and its connection to the spirit of the times, had dethroned the classics. Absent the mass appeal enjoyed by past masters like Beethoven, Verdi, Wagner and Tchaikovsky, modern composers had retreated into obscurantism, condemned to a futile search for novelty amid the detritus of a tradition that was, like overworked soil, exhausted and fallow. One could still love classical music, but only with the awareness that it was a relic of the past and in no way representative of our contemporary experience.

In 1955 Henry Pleasants, a critic of both popular and classical music, issued a cranky screed of a book, “The Agony of Modern Music,” which opened with the implacable verdict that “serious music is a dead art.” Pleasants’s thesis was that the traditional forms of classical music — opera, oratorio, orchestral and chamber music, all constructions of a bygone era — no longer related to the experience of our modern lives. Composers had lost touch with the currents of popular taste, and popular music, with its vitality and its connection to the spirit of the times, had dethroned the classics. Absent the mass appeal enjoyed by past masters like Beethoven, Verdi, Wagner and Tchaikovsky, modern composers had retreated into obscurantism, condemned to a futile search for novelty amid the detritus of a tradition that was, like overworked soil, exhausted and fallow. One could still love classical music, but only with the awareness that it was a relic of the past and in no way representative of our contemporary experience.

more here.

Saturday Poem

The Current

Having once put his hand into the ground,

seeding there what he hopes will outlast him,

a man has made a marriage with his place,

and if he leaves it his flesh will ache to go back.

His hand has given up its birdlife in the air.

It has reached into the dark like a root

and begun to wake, quick and mortal, in timelessness,

a flickering sap coursing upward into his head

so that he sees the old tribespeople bend

in the sun, digging with sticks, the forest opening

to receive their hills of corn, squash, and beans,

their lodges and graves, and closing again.

He is made their descendant, what they left

in the earth rising into him like a seasonal juice.

And he sees the bearers of his own blood arriving,

the forest burrowing into the earth as they come,

their hands gathering the stones up into walls,

and relaxing, the stones crawling back into the ground

to lie still under the black wheels of machines.

The current flowing to him through the earth

flows past him, and he sees one descended from him,

a young man who has reached into the ground,

his hand held in the dark as by a hand.

by Wendell Berry

from Farming- A Handbook

Harcourt Brace, 1970

Why Barbie Must Be Punished

Leslie Jamison in The New Yorker:

My childhood Barbies were always in trouble. I was constantly giving them diagnoses of rare diseases, performing risky surgeries to cure them, or else kidnapping them—jamming them into the deepest reaches of my closet, without plastic food or plastic water, so they could be saved again, returned to their plastic doll-cakes and their slightly-too-small wooden home. (My mother had drawn her lines in the sand; we had no Dreamhouse.) My abusive behavior was nothing special. Most girls I know liked to mess their Barbies up; and when it comes to child’s play, crisis is hardly unusual. It’s a way to make sense of the thrills and terrors of autonomy, the problem of other people’s desires, the brute force of parental disapproval. But there was something about Barbie that especially demanded crisis: her perfection. That’s why Barbie needed to have a special kind of surgery; why she was dying; why she was in danger. She was too flawless, something had to be wrong. I treated Barbie the way a mother with Munchausen syndrome by proxy might treat her child: I wanted to heal her, but I also needed her sick. I wanted to become Barbie, and I wanted to destroy her. I wanted her perfection, but I also wanted to punish her for being more perfect than I’d ever be.

My childhood Barbies were always in trouble. I was constantly giving them diagnoses of rare diseases, performing risky surgeries to cure them, or else kidnapping them—jamming them into the deepest reaches of my closet, without plastic food or plastic water, so they could be saved again, returned to their plastic doll-cakes and their slightly-too-small wooden home. (My mother had drawn her lines in the sand; we had no Dreamhouse.) My abusive behavior was nothing special. Most girls I know liked to mess their Barbies up; and when it comes to child’s play, crisis is hardly unusual. It’s a way to make sense of the thrills and terrors of autonomy, the problem of other people’s desires, the brute force of parental disapproval. But there was something about Barbie that especially demanded crisis: her perfection. That’s why Barbie needed to have a special kind of surgery; why she was dying; why she was in danger. She was too flawless, something had to be wrong. I treated Barbie the way a mother with Munchausen syndrome by proxy might treat her child: I wanted to heal her, but I also needed her sick. I wanted to become Barbie, and I wanted to destroy her. I wanted her perfection, but I also wanted to punish her for being more perfect than I’d ever be.

It’s not that I literally wanted to become her, of course—to wake up with a pair of hard plastic tits, coarse blond hair, waxy holes in my feet betraying the robotic fingerprint of my factory birthplace—but some part of me was already chasing the false gods she spoke for: beauty as a kind of spiritual guarantor, writing blank checks for my destiny; the self-effacing ease afforded by wealth and whiteness; selfhood as triumphant brand consistency, the erasure of opacity and self-destructive tendency. I craved all of these—still do, sometimes—even as my own awareness of their impossibility makes me want to destroy their false prophet: Barbie as snake-oil saleswoman hawking the existential and plasticine wares of her impossible femininity, one Pepto-Bismol-pink pet shop at a time.

More here.

Nobody Ever Read American Literature Like This Guy Did

A.O. Scott in The New York Times:

It has been a hundred years since D.H. Lawrence published “Studies in Classic American Literature,” and in the annals of literary criticism the book may still claim the widest discrepancy between title and content.

It has been a hundred years since D.H. Lawrence published “Studies in Classic American Literature,” and in the annals of literary criticism the book may still claim the widest discrepancy between title and content.

Not with respect to subject matter: As advertised, this compact volume consists of essays on canonical American authors of the 18th and 19th centuries — a familiar gathering of dead white men. Some (Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman) are still household names more than a century later, while others (Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, Richard Henry Dana Jr.) have faded into relative obscurity. By the 1950s, when American literature was fully established as a respectable field of academic study, Melville’s “Moby-Dick,” Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter,” Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” and Crèvecoeur’s “Letters From an American Farmer” had become staples of the college and grad school syllabus, which is where I and many others found them in the later decades of the 20th century. Thank goodness Lawrence got there first.

This is not going to be one of those laments about how nobody reads the great old books anymore. Not many people read them when they first appeared, either. My point is that nobody ever read them like Lawrence did — as madly, as wildly or as insightfully. That’s what I mean about the gap between the book and its title. “Studies in Classic American Literature” is as dull a phrase as any committee of professors could devise. Just try to say those five words without yawning. But look inside and you will be jolted awake.

The Origins of Metaphysics

One False Move: “Lock Things Up”

William Boyle at The Current:

I vividly remember picking up One False Move (1992) for the first time, and that box cover. Cynda Williams’s face over a sunset shoot-out—a beater car and a police cruiser framing four shadowy figures, three on one side taking position against the cop, who looks to be freshly shot, a scene that’s different from what happens in the film—and the title in a fat white font, a four-star blurb from Gene Siskel’s review above it: “A brilliant detective thriller.” It was a beautiful time for me. A time of wonder and discovery. I wasn’t reading reviews. No one was telling me what I had to see—I was the only person in my family interested in movies, and my friends only ever went to watch what was showing at the multiplexes. I rented One False Move that day and went home and loaded it in the VCR. I knew Bill Paxton from Weird Science (1985), Aliens (1986), and Near Dark (1987), but his was the only familiar face. That first viewing blew me away: the urgency and rawness, the complexity of the characters. Back then, I couldn’t articulate what I was reacting to, but what I can say now—all these years later, having written several novels that are crime dramas—is that I’m most drawn to stories that are rooted in character and place, with deep psychological undercurrents. In my personal canon, One False Move is the quintessential example of what I respond to within the genre. For my money, it’s a perfect crime movie, infused with desperate energy and moral ambiguity, one that doesn’t miss a beat, one whose effects linger and deepen.

more here.

How Truman Capote Was Destroyed by His Own Masterpiece

It’s 1965. Truman Capote was a known figure on the literary scene and a member of the global social jet set. His bestselling books Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s had made him a literary favorite. And after five years of painstaking research, and gut-wrenching personal investment, part I of In Cold Blood debuted in The New Yorker. As people across the country opened their magazines and read the first lines of the story, they were riveted. Overnight, Capote catapulted from a mere darling of the literary world to a full-fledged global celebrity on a par with the likes of rockstars and film legends.

It’s 1965. Truman Capote was a known figure on the literary scene and a member of the global social jet set. His bestselling books Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s had made him a literary favorite. And after five years of painstaking research, and gut-wrenching personal investment, part I of In Cold Blood debuted in The New Yorker. As people across the country opened their magazines and read the first lines of the story, they were riveted. Overnight, Capote catapulted from a mere darling of the literary world to a full-fledged global celebrity on a par with the likes of rockstars and film legends.

The success was all encompassing, but the cost would prove greater than even Capote had realized. Having read an article in the New York Times about the brutal slaying of a family at their farmhouse in Kansas, Capote embarked on a journey to the small rural farming town. Holcomb, located in Southwest Kansas, was a town of just under three hundred people and quintessential 1950s America. A small tight knit community that felt and acted more like one large family than a municipality.

more here.

The IBM mainframe: How it runs and why it survives

Andrew Hudson in Ars Technica:

Mainframe computers are often seen as ancient machines—practically dinosaurs. But mainframes, which are purpose-built to process enormous amounts of data, are still extremely relevant today. If they’re dinosaurs, they’re T-Rexes, and desktops and server computers are puny mammals to be trodden underfoot.

Mainframe computers are often seen as ancient machines—practically dinosaurs. But mainframes, which are purpose-built to process enormous amounts of data, are still extremely relevant today. If they’re dinosaurs, they’re T-Rexes, and desktops and server computers are puny mammals to be trodden underfoot.

It’s estimated that there are 10,000 mainframes in use today. They’re used almost exclusively by the largest companies in the world, including two-thirds of Fortune 500 companies, 45 of the world’s top 50 banks, eight of the top 10 insurers, seven of the top 10 global retailers, and eight of the top 10 telecommunications companies. And most of those mainframes come from IBM.

In this explainer, we’ll look at the IBM mainframe computer—what it is, how it works, and why it’s still going strong after over 50 years.

More here.

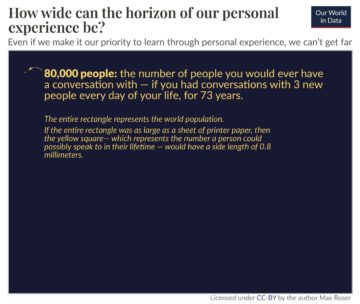

The limits of our personal experience and the value of statistics

Max Roser at Our World in Data:

It’s tempting to believe that we can simply rely on personal experience to develop our understanding of the world. But that’s a mistake. The world is large, and we can experience only very little of it personally. To see what the world is like, we need to rely on other means: carefully-collected global statistics.

It’s tempting to believe that we can simply rely on personal experience to develop our understanding of the world. But that’s a mistake. The world is large, and we can experience only very little of it personally. To see what the world is like, we need to rely on other means: carefully-collected global statistics.

Of course, our personal interactions are part of what informs our worldview. We piece together a picture of the lives of others around us from our interactions with them. Every time we meet people and hear about their lives, we add one more perspective to our worldview. This is a great way to see the world and expand our understanding, I don’t want to suggest otherwise. But I want to remind ourselves how little we can learn about our society through personal interactions alone, and how valuable statistics are in helping us build the rest of the picture.

More here.