Nicole Hannah-Jones in The New York Times:

My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine. Our corner lot, which had been redlined by the federal government, was along the river that divided the black side from the white side of our Iowa town. At the edge of our lawn, high on an aluminum pole, soared the flag, which my dad would replace as soon as it showed the slightest tatter.

My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine. Our corner lot, which had been redlined by the federal government, was along the river that divided the black side from the white side of our Iowa town. At the edge of our lawn, high on an aluminum pole, soared the flag, which my dad would replace as soon as it showed the slightest tatter.

My dad was born into a family of sharecroppers on a white plantation in Greenwood, Miss., where black people bent over cotton from can’t-see-in-the-morning to can’t-see-at-night, just as their enslaved ancestors had done not long before. The Mississippi of my dad’s youth was an apartheid state that subjugated its near-majority black population through breathtaking acts of violence. White residents in Mississippi lynched more black people than those in any other state in the country, and the white people in my dad’s home county lynched more black residents than those in any other county in Mississippi, often for such “crimes” as entering a room occupied by white women, bumping into a white girl or trying to start a sharecroppers union. My dad’s mother, like all the black people in Greenwood, could not vote, use the public library or find work other than toiling in the cotton fields or toiling in white people’s houses. So in the 1940s, she packed up her few belongings and her three small children and joined the flood of black Southerners fleeing North. She got off the Illinois Central Railroad in Waterloo, Iowa, only to have her hopes of the mythical Promised Land shattered when she learned that Jim Crow did not end at the Mason-Dixon line.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

The problem with trees is that they are too slow.

The problem with trees is that they are too slow. Like most people, I have been baffled, mystified, unimpressed and fascinated by

Like most people, I have been baffled, mystified, unimpressed and fascinated by

1. In nature the act of listening is primarily a survival strategy. More intense than hearing, listening is a proactive tool, affording animals a skill with which to detect predators nearby (defense mechanism), but also for predators to detect the presence and location of prey (offense mechanism).

1. In nature the act of listening is primarily a survival strategy. More intense than hearing, listening is a proactive tool, affording animals a skill with which to detect predators nearby (defense mechanism), but also for predators to detect the presence and location of prey (offense mechanism). Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, 2021.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, 2021.

A metal bucket with a snowman on it; a plastic faux-neon Christmas tree; a letter from Alexandra; an unsent letter to Alexandra; a small statuette of a world traveler missing his little plastic map; a snow globe showcasing a large white skull, with black sand floating around it.

A metal bucket with a snowman on it; a plastic faux-neon Christmas tree; a letter from Alexandra; an unsent letter to Alexandra; a small statuette of a world traveler missing his little plastic map; a snow globe showcasing a large white skull, with black sand floating around it.

I liked to play with chalk when I was little. Little kids did then. As far as I can tell they still do now. I walk and jog and drive around town for every other reason. Inevitably, I end up spotting many (maybe not

I liked to play with chalk when I was little. Little kids did then. As far as I can tell they still do now. I walk and jog and drive around town for every other reason. Inevitably, I end up spotting many (maybe not  Was there really a colony known as “Libertalia”, founded by Enlightened pirates on the north-east coast of Madagascar in the early 18th century?

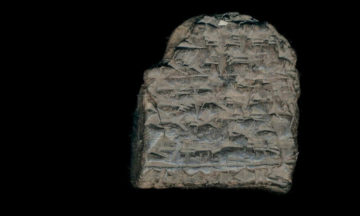

Was there really a colony known as “Libertalia”, founded by Enlightened pirates on the north-east coast of Madagascar in the early 18th century? I was sitting in a quiet office in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a clay tablet in my hand, using a magnifying glass to make out words that had been inscribed on it in small, careful, wedge-shaped signs known as cuneiform. It looked diminutive in my palm, just

I was sitting in a quiet office in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a clay tablet in my hand, using a magnifying glass to make out words that had been inscribed on it in small, careful, wedge-shaped signs known as cuneiform. It looked diminutive in my palm, just  Cities are incredibly important to modern life, and their importance is only growing. As

Cities are incredibly important to modern life, and their importance is only growing. As  Steven Pinker thinks ChatGPT is truly impressive — and will be even more so once it “stops making stuff up” and becomes less error-prone. Higher education, indeed, much of the world, was set abuzz in November when OpenAI unveiled its ChatGPT chatbot capable of instantly answering questions (in fact, composing writing in various genres) across a range of fields in a conversational and ostensibly authoritative fashion. Utilizing a type of AI called a large language model (LLM), ChatGPT is able to continuously learn and improve its responses. But just how good can it get?

Steven Pinker thinks ChatGPT is truly impressive — and will be even more so once it “stops making stuff up” and becomes less error-prone. Higher education, indeed, much of the world, was set abuzz in November when OpenAI unveiled its ChatGPT chatbot capable of instantly answering questions (in fact, composing writing in various genres) across a range of fields in a conversational and ostensibly authoritative fashion. Utilizing a type of AI called a large language model (LLM), ChatGPT is able to continuously learn and improve its responses. But just how good can it get?