Amanda H Podany in Aeon:

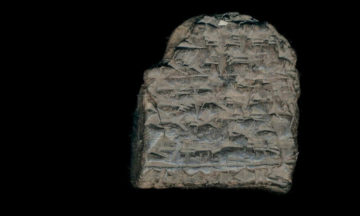

I was sitting in a quiet office in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a clay tablet in my hand, using a magnifying glass to make out words that had been inscribed on it in small, careful, wedge-shaped signs known as cuneiform. It looked diminutive in my palm, just 38.5 mm (1.5 inches) wide and 33 mm (1.3 inches) tall. On it, an ancient scribe had written a list of a dozen names. What lay behind this little document? Who were the men listed? When and how did they live? More than 3,700 years ago, when the scribe used his sharp stylus to press the names into the clay, listing goods distributed to each person, these men knew one another and worked together. Many of them must have had wives and families and professions. What more could I learn about their world?

I was sitting in a quiet office in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a clay tablet in my hand, using a magnifying glass to make out words that had been inscribed on it in small, careful, wedge-shaped signs known as cuneiform. It looked diminutive in my palm, just 38.5 mm (1.5 inches) wide and 33 mm (1.3 inches) tall. On it, an ancient scribe had written a list of a dozen names. What lay behind this little document? Who were the men listed? When and how did they live? More than 3,700 years ago, when the scribe used his sharp stylus to press the names into the clay, listing goods distributed to each person, these men knew one another and worked together. Many of them must have had wives and families and professions. What more could I learn about their world?

At that point, I was just beginning my graduate research in ancient Middle Eastern history, but I knew I was not the first person to read this tablet. Decades before, in 1923, a French scholar named François Thureau-Dangin had travelled to eastern Syria, searching for the site of an ancient city called Terqa, and he had been given this tablet, along with a handful of others, and had brought them back to the Louvre.

More here.