Erik Stokstad in Science:

NORTHFIELD, WISCONSIN—When drivers on Highway 94 pass this tiny town, some are struck by a mysterious nocturnal glow. Pink light emanates from the world’s largest aquaponic greenhouse, which can produce up to 2 million kilograms of salad greens each year. Less obvious, but also unique at this scale, is the source of the nutrients used to fertilize the crops: wastewater flowing from huge nearby tanks teeming with Atlantic salmon. The silvery fish grow indoors, far from the ocean where wild salmon normally spend the bulk of their lives.

NORTHFIELD, WISCONSIN—When drivers on Highway 94 pass this tiny town, some are struck by a mysterious nocturnal glow. Pink light emanates from the world’s largest aquaponic greenhouse, which can produce up to 2 million kilograms of salad greens each year. Less obvious, but also unique at this scale, is the source of the nutrients used to fertilize the crops: wastewater flowing from huge nearby tanks teeming with Atlantic salmon. The silvery fish grow indoors, far from the ocean where wild salmon normally spend the bulk of their lives.

On a recent winter day, the surrounding farmland blanketed in snow, Steve Summerfelt opened the door to the fish house. Hundreds of meter-long fish swam vigorously in each house-size tank, while an overhead crane delivered a 1-ton sack of feed into an automated dispenser. Rumbling pumps and tanks filled with sand, separated from the fish tanks by a soundproof wall, treated wastewater that had been stripped of fish poop. Nitrogen and phosphorus were diverted to the vast greenhouse while cleansed water recirculated to the salmon. “Sometimes the water is so clean it looks like the fish are swimming in air,” says Summerfelt, an engineer who is head of R&D at the company, called Superior Fresh.

More here.

In his generous

In his generous Almost

Almost Fascination with the ancient Egyptians seems nigh inexhaustible. And why wouldn’t it be? There are all those pyramids, so pleasingly geometric against the stark and sandy landscape. In the pyramids, in those giant tombs, massive hoards of treasure. And at the very center of those hoards of gold and bejeweled items, mummies. How can one not be fascinated by mummies? They are corpses and corpses are tantalizing. But not just any corpses, corpses of kings and queens. Death, but death preserved for centuries and eons, for eternity.

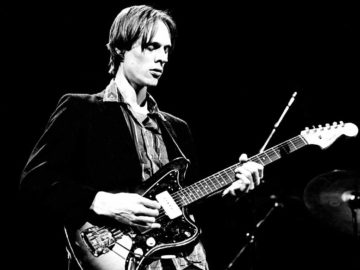

Fascination with the ancient Egyptians seems nigh inexhaustible. And why wouldn’t it be? There are all those pyramids, so pleasingly geometric against the stark and sandy landscape. In the pyramids, in those giant tombs, massive hoards of treasure. And at the very center of those hoards of gold and bejeweled items, mummies. How can one not be fascinated by mummies? They are corpses and corpses are tantalizing. But not just any corpses, corpses of kings and queens. Death, but death preserved for centuries and eons, for eternity. On the other hand, the qualities that made Tarantino the most talked about American filmmaker of his generation have also transferred cleanly into his new role as a writer of books. Quentin Tarantino is to movies what Diego Maradona was to football ‑ not just someone who does it to an exceptional level but a being entirely made of cinema, a tulpa born of the screen whose existence is ecstatically wedded to it. Tarantino has always been a joyous appreciator of movies, and the first thing to be said for his writing is that that infectious fanaticism is there on every page. The core delight of Cinema Speculation is that of being invited into the warmth of someone else’s lifelong love affair. Granted, Tarantino’s enthusiasm is so instinctively anti-hierarchical that it sometimes feels as if he has no capacity for critical discernment at all ‑ and yet, such is the enlivening force of his passion that, rather than serve as a fatal mark against him, this has quite the opposite effect. There is little he hates, or at least he has no interest in talking about anything that bores him or leaves him indifferent (bar the odd swipe at worthy 1980s fare ‑ the 1988 adaptation of Milan Kundera’s novel, he suggests, ought to have been titled The Unbearable Boredom of Watching). He ardently admires virtually every slasher movie, car-chase spectacle, heist-thriller or splatterhouse revenge-rampage ever filmed, as if discerning in each humble movie an emanation of The Movies, a divine substrate that dwells behind the screen like God beyond the skies. This boundless enthusiasm, along with that unmistakeable voice ‑ relentless, cheerful, vulgar, demotic ‑ make for attractive qualities in a writer. There’s nothing forced in Cinema Speculation; it never feels as if Tarantino is writing merely to fulfil a contractual obligation.

On the other hand, the qualities that made Tarantino the most talked about American filmmaker of his generation have also transferred cleanly into his new role as a writer of books. Quentin Tarantino is to movies what Diego Maradona was to football ‑ not just someone who does it to an exceptional level but a being entirely made of cinema, a tulpa born of the screen whose existence is ecstatically wedded to it. Tarantino has always been a joyous appreciator of movies, and the first thing to be said for his writing is that that infectious fanaticism is there on every page. The core delight of Cinema Speculation is that of being invited into the warmth of someone else’s lifelong love affair. Granted, Tarantino’s enthusiasm is so instinctively anti-hierarchical that it sometimes feels as if he has no capacity for critical discernment at all ‑ and yet, such is the enlivening force of his passion that, rather than serve as a fatal mark against him, this has quite the opposite effect. There is little he hates, or at least he has no interest in talking about anything that bores him or leaves him indifferent (bar the odd swipe at worthy 1980s fare ‑ the 1988 adaptation of Milan Kundera’s novel, he suggests, ought to have been titled The Unbearable Boredom of Watching). He ardently admires virtually every slasher movie, car-chase spectacle, heist-thriller or splatterhouse revenge-rampage ever filmed, as if discerning in each humble movie an emanation of The Movies, a divine substrate that dwells behind the screen like God beyond the skies. This boundless enthusiasm, along with that unmistakeable voice ‑ relentless, cheerful, vulgar, demotic ‑ make for attractive qualities in a writer. There’s nothing forced in Cinema Speculation; it never feels as if Tarantino is writing merely to fulfil a contractual obligation.

Talk about a comeback.

Talk about a comeback. I know, I know. The value of Black history can’t be contained in only a month. And one can’t define whether a month is “good” or “bad” based on what is happening in the news cycle.

I know, I know. The value of Black history can’t be contained in only a month. And one can’t define whether a month is “good” or “bad” based on what is happening in the news cycle.

In The Art of Revision: The Last Word, Peter Ho Davies notes that writers often have multiple ways to approach the revision of a story. “The main thing,” he writes, “is not to get hung up on the choice; try one and find out. … Sometimes the only way to choose the right option is to choose the wrong one first.” I’m easily hung up on choices of all kinds, and I read those words with a sense of relief.

In The Art of Revision: The Last Word, Peter Ho Davies notes that writers often have multiple ways to approach the revision of a story. “The main thing,” he writes, “is not to get hung up on the choice; try one and find out. … Sometimes the only way to choose the right option is to choose the wrong one first.” I’m easily hung up on choices of all kinds, and I read those words with a sense of relief. A friend just sent me a copy of materials that the Cornwall Alliance is sending to its supporters. Here is an extract [fair use claimed]:

A friend just sent me a copy of materials that the Cornwall Alliance is sending to its supporters. Here is an extract [fair use claimed]: