Month: February 2023

Salman Rushdie on the enduring beauty of the Taj Mahal

Salman Rushdie in National Geographic:

The trouble with India’s Taj Mahal is that it has become so overlaid with accumulated meanings as to be almost impossible to see. A billion chocolate-box images and tourist guidebooks order us to “read” the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s marble mausoleum for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, known as “Taj Bibi,” as the World’s Greatest Monument to Love. It sits at the top of the West’s short list of images of the Exotic (and also Timeless) Orient. Like the Mona Lisa, like Andy Warhol’s silk-screened Elvis, Marilyn, and Mao, mass reproduction has all but sterilized the Taj Mahal.

The trouble with India’s Taj Mahal is that it has become so overlaid with accumulated meanings as to be almost impossible to see. A billion chocolate-box images and tourist guidebooks order us to “read” the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s marble mausoleum for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, known as “Taj Bibi,” as the World’s Greatest Monument to Love. It sits at the top of the West’s short list of images of the Exotic (and also Timeless) Orient. Like the Mona Lisa, like Andy Warhol’s silk-screened Elvis, Marilyn, and Mao, mass reproduction has all but sterilized the Taj Mahal.

Nor is this by any means a simple case of the West’s appropriation or “colonization” of an Indian masterwork. In the first place, the Taj, which in the mid-19th century had been all but abandoned and had fallen into a severe state of disrepair, would probably not be standing today were it not for the diligent conservationist efforts of the colonial British. In the second place, India is perfectly capable of over merchandising itself.

More here.

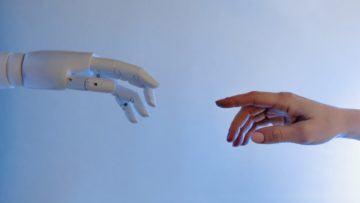

Love and Loathing in the Time of ChatGPT

by Ali Minai

Recently, I asked the students in my class whether they had used ChatGPT, the artificially intelligent chatbot recently loosed upon the world by OpenAI. My question was motivated by a vague thought that I might ask them to use the system as a whimsical diversion within an assignment. Somewhat to my surprise, every student had used the system. Perhaps I should not have been surprised given the volume of chatter about ChatGPT on my social media feeds and my own obsessive “playing” with it for some time after being introduced to it. There is clearly something about this critter that has been lacking in all the vaunted AI systems before it. That something, of course, is how well it fits in with the human need to converse. Very few of us want to play chess or Go with AI; generating cute pictures from absurd prompts is interesting but only in a superficial way; and generating truly complex art with AI is still not something that a non-technical person can do easily. But everyone can engage in conversation with a responsive companion – a pocket friend with a seemingly endless supply of occasionally quite interesting things to say. For all that it lives out in the ether somewhere, it seems pretty human. And this, let it be stated at the outset, makes ChatGPT an immense achievement in the field of AI, and truly a harbinger of the future.

Recently, I asked the students in my class whether they had used ChatGPT, the artificially intelligent chatbot recently loosed upon the world by OpenAI. My question was motivated by a vague thought that I might ask them to use the system as a whimsical diversion within an assignment. Somewhat to my surprise, every student had used the system. Perhaps I should not have been surprised given the volume of chatter about ChatGPT on my social media feeds and my own obsessive “playing” with it for some time after being introduced to it. There is clearly something about this critter that has been lacking in all the vaunted AI systems before it. That something, of course, is how well it fits in with the human need to converse. Very few of us want to play chess or Go with AI; generating cute pictures from absurd prompts is interesting but only in a superficial way; and generating truly complex art with AI is still not something that a non-technical person can do easily. But everyone can engage in conversation with a responsive companion – a pocket friend with a seemingly endless supply of occasionally quite interesting things to say. For all that it lives out in the ether somewhere, it seems pretty human. And this, let it be stated at the outset, makes ChatGPT an immense achievement in the field of AI, and truly a harbinger of the future.

What is ChatGPT – Really?

As anyone who has played with ChatGPT knows, it is a system that answers queries and carries on conversations – hence the term chatbot. In this, it is similar to Alexa, Siri, et al. But it is interesting to look a little more closely at how it works because that is key to its strengths and weaknesses. Read more »

At a loss with biodiversity loss?

by Raji Jayaraman

Scientists estimate that 1 in 6 bee species are extinct and 40 percent are at the verge of extinction due to habitat loss and pesticide use. The consequences are dire. Bees are major pollinators of food crops. Their extinction would threaten the earth’s ecosystem, and food chains upon which we all depend. Many of us already know this since bees have the dubious distinction of being extinction celebrities. But bees are only one part of the calamitous biodiversity loss the world has suffered in the last five decades. The World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London estimate, for example, that between 1970 and 2018, there was an average 69% decline in wildlife populations across the globe, and an 83% decline in global freshwater species. Scientists believe we are in the throes of a mass extinction (earth’s sixth), with species dying out at several hundred-fold their expected rate thanks to human activity.

Declines in biodiversity pose an existential threat to life on earth. We rely on biodiversity for our food, air, water, medicine, and almost everything else that we need to sustain humanity. Yet most people don’t even know what biodiversity means, let alone what to do about it. Definitions are a good place to start. According to the Convention on Biological Diversity, biodiversity refers to the “variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.”

As a lay person, the only clarity this definition adds to the word itself is that biodiversity is complicated. Its complexity–arising from the scale and diversity of species, their interconnectedness, lack of data, and spatial as well as temporal heterogeneity–makes biodiversity a very difficult problem to model. There are 8.7 million species on earth. What happens when one of the 42,000 that feature on the IUCN’s red list of species threatened with extinction goes extinct? How much do we even know about any of them? What are the ripple effects of species extinction on the intricate web of life, locally, globally, today, and tomorrow? Read more »

Monday Poem

My Boat and I

My boat’s sail is the puffed dust of crescent moon

rigged on its mast at almost-opposite of noon

My boat & I once were moving slow,

but now we’re moving fast. My boat & I

are cruising into future from that which doesn’t last,

tacking through present redolent of night and day

which will last as long as it will last.

As long as it will last we’ll stay.

We’ll stay as long as we can stay,

my boat and I

Jim Culleny, © 3/3/21

Photo, Daily Mail

Strongmen Leaders and the Infallibility Trap

by Thomas R. Wells

It is easy to become exasperated with liberal democracy. Various factions bicker and manoeuvre against each other in an endless grubby contest for power, hypocritically appealing to a shared public interest while continuously generating and sustaining social divisions. Things that are necessary – like addressing climate change – do not get done, lost amidst the endless dithering, quibbling, and bargaining for advantage. Things that should not be done – like deporting UK asylum applicants to Rwanda – become official policy against all common sense and multiple laws, seemingly mainly as a way of trolling the opposition and civil society.

So it is disappointing but perhaps not surprising that people around the world are increasingly likely to endorse the strongman theory of government, that “a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and election is a good way to run the country”.

Strongman government has two major attractions compared to liberal democracy. First, it promises wise and benevolent rule: undistracted by factions motivated by political interests the strong leader will be freed to make wiser, better decisions in the national interest. Second, it promises decisiveness: without the endless bickering and second guessing, strong leaders can get on and do what needs to be done.

In what follows I want to challenge these apparent advantages and show that the very failings of liberal democracy are actually the solution to the problems that strongman governments run into. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Untitled. Rwanda, January 2023.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. Rwanda, January 2023.

Digital photograph.

Late Night Thoughts on “The Things They Carried”

by Joseph Shieber

I’ve finally gotten around to reading Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried.

One aspect of the book that makes it so great is the way that O’Brien makes the challenge of the ineffability of his – and his comrades’ – war experiences part of the book itself. For example, he writes:

In many cases a true war story cannot be believed. If you believe it, be skeptical. It’s a question of credibility. Often the crazy stuff is true and the normal stuff isn’t, because the normal stuff is necessary to make you believe the truly incredible craziness. In other cases you can’t even tell a true war story. Sometimes it’s just beyond telling.

Reading the book in this way reminded me of the brilliant poem by James Fenton, “A German Requiem” (from The Memory of War and Children in Exile, Penguin, 1983). Read more »

Gödel’s Proof and Einstein’s Dice: Undecidability in Mathematics and Physics – Part I

by Jochen Szangolies

TWA Flight 702 left New York at 7 AM on Monday, Feb. 4 1974, to arrive in London at 7 PM—some 40 minutes early. We know this thanks to the meticulous note-taking habits of visionary physicist John Archibald Wheeler, coiner of such colorful terms as ‘quantum foam’, ‘wormhole’, ‘superspace’ and ‘black hole’.

Wheeler spent the flight occupied with what he is perhaps best remembered for: pondering his ‘Really Big Questions’ (RBQs), among which we find perennial mysteries such as ‘How come existence?’ or ‘What makes meaning?’. The RBQ that occupied Wheeler on this particular day, however, was one that in many ways lay at the nexus of his thought: ‘Why the quantum?’

Wheeler had been a student of Bohr and Einstein, and thus, had learned about quantum mechanics straight from the horse’s mouth. Yet, he would struggle with the implications of the theory for the rest of his life, referring to the fundamental indefiniteness of its phenomena as the ‘great smoky dragon’. He was searching for a way to dispel the smoke, and in the note composed on Flight 702, draws a surprising connection to another remote frontier of human understanding—the phenomenon of mathematical undecidability, as discovered in 1931 by the then-25 year old logician Kurt Gödel. (The note itself is available online at the John Archibald Wheeler Archive curated by Baruch Garcia.)

At first sight, one might suppose this connection to be little more than a kind of ‘parsimony of mystery’: in substituting one riddle for another, the total number of unknowns is reduced. Indeed, the idea of ripping Gödel’s result from the austere domain of mathematical logic and injecting it into physical theory is controversial—earlier, during the writing of his magisterial textbook on General Relativity, Gravitation, with Charles Misner and Kip Thorne, Wheeler had confronted Gödel himself with the idea, who did not react too enthusiastically. Read more »

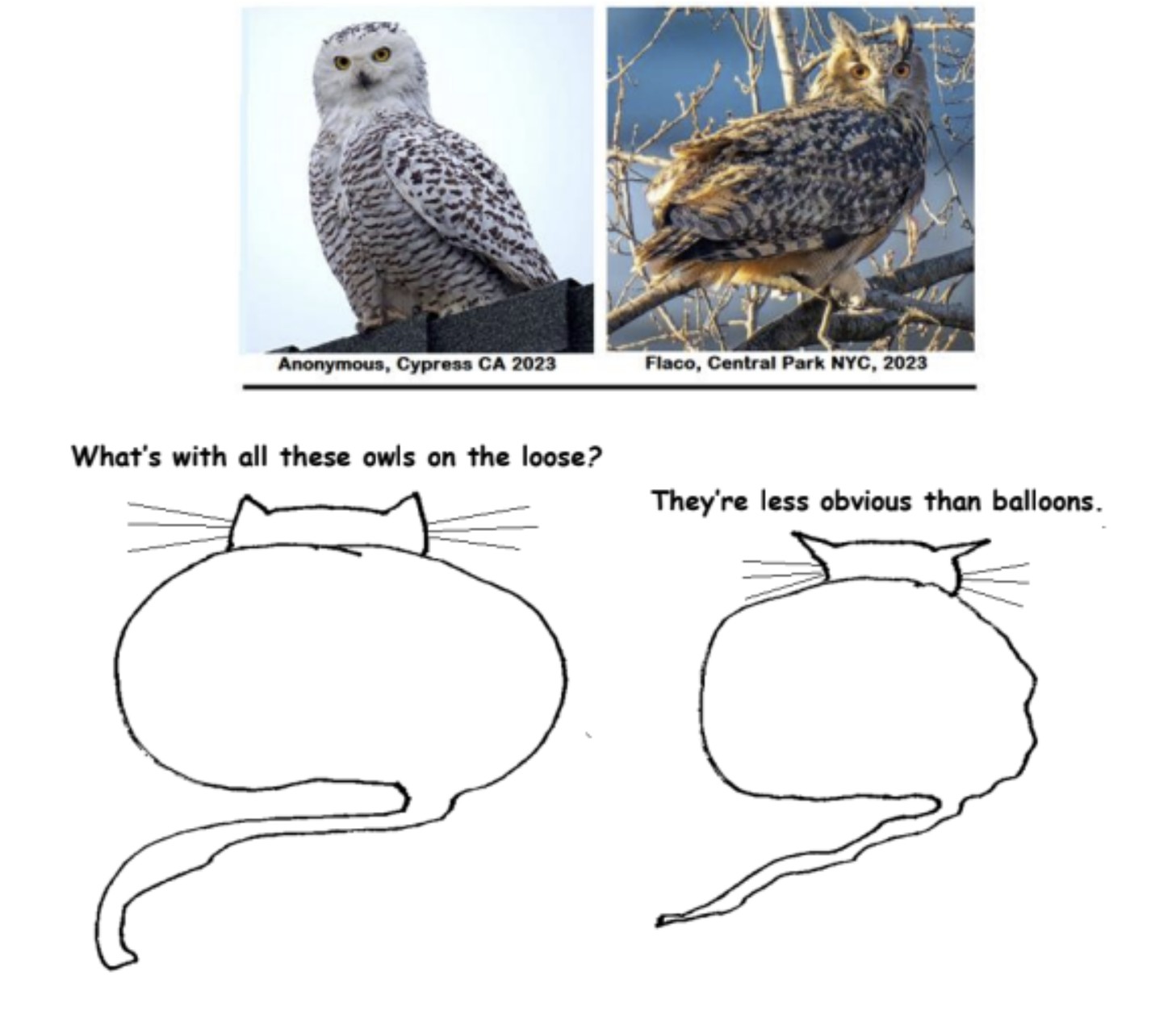

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Thoughts on Classical and Metal Music: Counterpoint and Motion

by Rebecca Baumgartner

The cultural cachet of classical music and the countercultural tone of metal music would initially seem at odds with each other – one represents the Man, the other rails against him. Even many of the aficionados of both types of music would agree with that assessment. However, the listener unencumbered with such stereotypes can appreciate the similarities in both genres of music, similarities both of musical form and structure, as well as in the subjective experience of the listener.

There are many technical similarities between classical music, especially music from the baroque period, and metal, which others more versed in music theory are better qualified than I am to discuss. At a fundamental level, both types of music are interested in exploring complexity. Sometimes this can appear like complexity for the sake of complexity, giving us the negative connotations of the word “baroque” (as in “the baroque language of government documents”). However, both the best baroque music and the best metal put their complexity to work in the service of building a musical architecture, an abstract structure that keeps the brain in motion, trying to work out how the pieces fit together.

Examples are numerous, so to narrow the field a bit, I want to focus on two concepts that are critical in creating that complexity, and how it makes both types of music more intellectually satisfying and fulfilling than your standard Top 40 hits. Those concepts are counterpoint and movement. Read more »

Technology: Instrumental, Determining, or Mediating?

by Fabio Tollon

We take words quite seriously. We also take actions quite seriously. We don’t take things as seriously, but this is changing.

We live in a society where the value of a ‘thing’ is often linked to, or determined by, what it can do or what it can be used for. Underlying this is an assumption about the value of “things”: their only value consists in the things they can do. Call this instrumentalism. Instrumentalism, about technology more generally, is an especially intuitive idea. Technological artifacts (‘things’) have no agency of their own, would not exist without humans, and therefore are simply tools that are there to be used by us. Their value lies in how we decide to use them, which opens up the possibility of radical improvement to our lives. Technology is a neutral means with which we can achieve human goals, whether these be good or evil.

In contrast to this instrumentalist view there is another view on technology, which claims that technology is not neutral at all, but that it instead has a controlling or alienating influence on society. Call this view technological determinism. Such determinism regarding technology is often justified by, well, looking around. The determinist thinks that technological systems take us further away from an ‘authentic’ reality, or that those with power develop and deploy technologies in ways that increase their ability to control others.

So, the instrumentalist view sees some promise in technology, and the determinist not so much. However, there is in fact a third way to think about this issue: mediation theory. Dutch philosopher Peter-Paul Verbeek, drawing on the postphenomenological work of Don Ihde, has proposed a “thingy turn” in our thinking about the philosophy of technology. This we can call the mediation account of technology. This takes us away from both technological determinism and instrumentalism. Here’s how. Read more »

Monday Photo

Thinking of You: On Grace

by Michael Abraham

The shower is running. It has just begun to steam up the little bathroom in my little apartment, and I reach into it, turn the dial from all-the-way-hot to almost-all-the-way-hot. I step into the spray of the water, and I discover that, instead of almost-all-the-way-hot, I have turned the dial to nearly-tepid. I turn it back toward all-the-way-hot, and, almost immediately, I feel it scald my chest. I fuss with it. I fuss back and forth with the dial in my shower, and, as I do so, I think of you, whoever you are, whoever you are reading this essay or whoever you are who is not reading this essay and never will. I think of you, out there, in your bathroom, taking a shower in the early afternoon on a lazy day off, fussing with the dial or the handles or whatever contraption it is that controls the heat in your shower, finding yourself now scalded, now freezing. I think of you, of how we have this experience in common—this bare, quotidian experience that means nothing on its surface, that is easily forgotten in the moments after it happens, for it happens so frequently and with such little fanfare. I am thinking of you as I pick up the bar soap and soap my body. I wonder if you use bar soap, too, or if you are a shower gel kind of person. I feel fairly confident we share the experience of shampoo, but I reflect that not everyone conditions as I condition my hair. When I step out of the shower and am met with a bathroom that feels much more bracingly cold than it did when I stepped into it, I think of you as well, at how the hairs on your arms raise just like mine.

You see, I have been thinking of you a lot these days. I have been thinking of all the small, seemingly menial things that happen to me that also happen to you, of the way you swear under your breath when you burn the rice—how you cut your finger on the corner of the page of a book—how you are enchanted for a moment by a gust of wind and brought back to memories of playing in leaves as a child—how you make too much coffee and then drink too much coffee and then find yourself with a stomach ache and a buzzing mind. Read more »

The Sad Prince

by Derek Neal

If Joan Didion were alive today, she might write an essay about Prince Harry and include it in an updated version of Slouching Towards Bethlehem. She might write a passage like the one she wrote about Howard Hughes:

If Joan Didion were alive today, she might write an essay about Prince Harry and include it in an updated version of Slouching Towards Bethlehem. She might write a passage like the one she wrote about Howard Hughes:

That we have made a hero of Howard Hughes tells us something interesting about ourselves, something only dimly remembered, tells us the secret point of money and power in America is neither the things that money can buy nor power for power’s sake (Americans are uneasy with their possessions, guilty about power, all of which is difficult for Europeans to perceive because they are themselves so truly materialistic, so versed in the uses of power), but absolute personal freedom, mobility, privacy. It is the instinct which drove America to the Pacific, all through the nineteenth century, the desire to be able to find a restaurant open in case you want a sandwich, to be a free agent, live by one’s own rules.

Didion’s comment about finding a restaurant open for a sandwich comes from a remark she’d heard as an explanation for Hughes buying up real estate in Las Vegas. It may seem a bit much to procure a whole town as a way of ensuring you can get a bite to eat at 3 pm in the afternoon, or 3 am in the morning, but have you ever been to Europe? My first experience of Europe was a year abroad studying in Nice, France. One day, I planned to get together with an American friend for lunch. We figured we’d meet up in the old city center, walk around a bit, then pick a place that looked good. As it happened, we were both running a little late, then we strolled around a bit too long, and finally we walked into a restaurant at about, well, 3 pm. Ever the innocents abroad, we had yet to realize our fatal error. The restaurant was deserted, and we had difficulty finding someone who worked there. Eventually, we did. After we bumbled along in our best French, asking if we could eat there and feeling confused as to why we had to ask, the proprietor cast his cold gaze upon us and proclaimed that, in France, restaurants close between lunch and dinner time. The kitchen, he said, is closed. We were stunned. Were the social conventions truly so strong that they couldn’t be amended for us, two Americans, who just wanted something to eat and secretly felt that we deserved something to eat, as well? Were we really going to be turned away? We had money, after all. Read more »

The Philosophy of Mourning

Paul J. Griffiths in Commonweal:

But what, exactly, is mourning, and how does doing it well contribute to a fully human life? These are good questions, addressed too rarely. In Imagining the End, Jonathan Lear takes them on with his usual learning, verve, and lucidity. Lear, who has taught at the University of Chicago since the 1990s, has written prolifically on various fundamental aspects of human life—including hope, love, illness, and irony, with Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, Freud, Kierkegaard, and Wittgenstein among his most frequent interlocutors. He is always concerned with the texture of human life: how it is woven, how it can become unwoven, what its principal virtues are. He wants to know how we should live, and on that question he is among our most intelligent guides.

But what, exactly, is mourning, and how does doing it well contribute to a fully human life? These are good questions, addressed too rarely. In Imagining the End, Jonathan Lear takes them on with his usual learning, verve, and lucidity. Lear, who has taught at the University of Chicago since the 1990s, has written prolifically on various fundamental aspects of human life—including hope, love, illness, and irony, with Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, Freud, Kierkegaard, and Wittgenstein among his most frequent interlocutors. He is always concerned with the texture of human life: how it is woven, how it can become unwoven, what its principal virtues are. He wants to know how we should live, and on that question he is among our most intelligent guides.

More here.

A ‘De-extinction’ Company Wants to Bring Back the Dodo

Christine Kenneally in Scientific American:

Colossal Biosciences, the headline-grabbing, venture-capital-funded juggernaut of de-extinction science, announced plans on January 31 to bring back the dodo. Whether “bringing back” a semblance of the extinct flightless bird is feasible is a matter of debate.

Colossal Biosciences, the headline-grabbing, venture-capital-funded juggernaut of de-extinction science, announced plans on January 31 to bring back the dodo. Whether “bringing back” a semblance of the extinct flightless bird is feasible is a matter of debate.

Founded in 2021 by tech entrepreneur Ben Lamm and Harvard University geneticist George Church, the company first said it would re-create the mammoth. And a year later it announced such an effort for the thylacine, aka the Tasmanian tiger. Now, with the launch of a new Avian Genomics Group and a reported $150 million of additional investment, the long-gone dodo joins the lineup.

More here.

What international law says about Israel’s planned destruction of Palestinian assailants’ homes

Robert Goldman in The Conversation:

Israel has demolished the homes of thousands of Palestinians in recent years. Bulldozing properties of those deemed responsible for violent acts against Israeli citizens or to deter such acts has long been government policy.

Israel has demolished the homes of thousands of Palestinians in recent years. Bulldozing properties of those deemed responsible for violent acts against Israeli citizens or to deter such acts has long been government policy.

But it is also illegal under international law. As an expert on international humanitarian law, I know that holding the family of assailants responsible for their acts – no matter how heinous the crime – falls under what is know as collective punishment. And for the past 70-plus years, international law has been unequivocal: Collective punishment is strictly prohibited in nearly all circumstances. Yet, when it comes to the demolition of Palestinian homes, international bodies have been unable to enforce the ban.

More here.

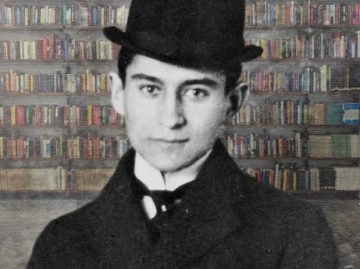

Kafka’s Remarkable Letter to His Abusive Father

From The Marginalian:

Prompted in large part by the dissolution of his engagement to Felice Bauer, in which Hermann’s active disapproval of the relationship was a toxic force and which resulted in the estrangement of father and son, 36-year-old Kafka set out to hold his father accountable for the emotional abuse, disorienting double standards, and constant disapprobation that branded his childhood — a measured yet fierce outburst of anguish and disappointment thirty years in the buildup.

Prompted in large part by the dissolution of his engagement to Felice Bauer, in which Hermann’s active disapproval of the relationship was a toxic force and which resulted in the estrangement of father and son, 36-year-old Kafka set out to hold his father accountable for the emotional abuse, disorienting double standards, and constant disapprobation that branded his childhood — a measured yet fierce outburst of anguish and disappointment thirty years in the buildup.

His litany of indictments is doubly harrowing in light of what psychologists have found in the decades since — that our early limbic contact with our parents profoundly shapes our character, laying down the wiring for emotional habits and patterns of connecting that greatly influence what we bring to all subsequent relationships in life, either expanding or contracting our capacity for “positivity resonance” depending on how nurturing or toxic those formative relationships were.

More here.

Education has become an investment. But what are its returns?

Eleni Schirmer in Lapham’s Quarterly:

Higher education in the United States is a speculative endeavor. It offers a means of inching toward something that does not quite exist but that we very badly want to realize—enlightenment, higher wages, national security. For individuals, it provides the lure of upward mobility, an illusion of escape from the lowest rungs of the labor market. For the federal government, it has charted a kind of statecraft, outlining its core commitments to military strength and economic growth, all the while absolving the state of the responsibility for ensuring that all its subjects have dignified means to live. We are told the path to decent wages and social respect must route through college.

Higher education in the United States is a speculative endeavor. It offers a means of inching toward something that does not quite exist but that we very badly want to realize—enlightenment, higher wages, national security. For individuals, it provides the lure of upward mobility, an illusion of escape from the lowest rungs of the labor market. For the federal government, it has charted a kind of statecraft, outlining its core commitments to military strength and economic growth, all the while absolving the state of the responsibility for ensuring that all its subjects have dignified means to live. We are told the path to decent wages and social respect must route through college.

The metric of higher education is credit; it runs on the belief of future value amid present uncertainty. This has readily lent to the industry’s financialization, the elaborate ways of using money to make more money rather than to produce goods and services. Today financialized systems of higher education mean that colleges and universities operate as investors or borrowers or both.

More here.