Robin Kelley in The Boston Review:

In the fall of 2015, college campuses were engulfed by fires ignited in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri. This is not to say that college students had until then been quiet in the face of police violence against black Americans. Throughout the previous year, it had often been college students who hit the streets, blocked traffic, occupied the halls of justice and malls of America, disrupted political campaign rallies, and risked arrest to protest the torture and suffocation of Eric Garner, the abuse and death of Sandra Bland, the executions of Tamir Rice, Ezell Ford, Tanisha Anderson, Walter Scott, Tony Robinson, Freddie Gray, ad infinitum.

In the fall of 2015, college campuses were engulfed by fires ignited in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri. This is not to say that college students had until then been quiet in the face of police violence against black Americans. Throughout the previous year, it had often been college students who hit the streets, blocked traffic, occupied the halls of justice and malls of America, disrupted political campaign rallies, and risked arrest to protest the torture and suffocation of Eric Garner, the abuse and death of Sandra Bland, the executions of Tamir Rice, Ezell Ford, Tanisha Anderson, Walter Scott, Tony Robinson, Freddie Gray, ad infinitum.

That the fire this time spread from the town to the campus is consistent with historical patterns. The campus revolts of the 1960s, for example, followed the Harlem and Watts rebellions, the freedom movement in the South, and the rise of militant organizations in the cities. But the size, speed, intensity, and character of recent student uprisings caught much of the country off guard. Protests against campus racism and the ethics of universities’ financial entanglements erupted on nearly ninety campuses, including Brandeis, Yale, Princeton, Brown, Harvard, Claremont McKenna, Smith, Amherst, UCLA, Oberlin, Tufts, and the University of North Carolina, both Chapel Hill and Greensboro. These demonstrations were led largely by black students, as well as coalitions made up of students of color, queer folks, undocumented immigrants, and allied whites.

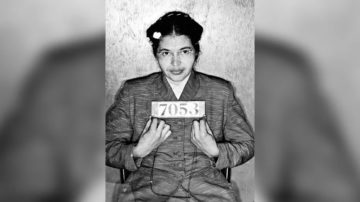

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

A: I don’t even have cable anymore.

A: I don’t even have cable anymore. For most of 2022 I was quietly working on my second book,

For most of 2022 I was quietly working on my second book,  The story of Babel is the best metaphor I’ve found for making sense of the momentous sociological, cultural, and epistemological changes that occurred in many nations in the early 2010s, which gave us the chaos, fragmentation, and outrage that began to set in by the mid-2010s. There are many causes of the transformation, but I believe that the largest single cause was the rapid conversion,

The story of Babel is the best metaphor I’ve found for making sense of the momentous sociological, cultural, and epistemological changes that occurred in many nations in the early 2010s, which gave us the chaos, fragmentation, and outrage that began to set in by the mid-2010s. There are many causes of the transformation, but I believe that the largest single cause was the rapid conversion,  D&D gets its appetite for rules from wargames, which have been around for thousands of years. The modern war game began in the late eighteenth century, when a certain Helwig, the Master of Pages to the German Duke of Brunswick, invented something called “War Chess”: instead of rooks and knights and pawns it featured cavalry, artillery and infantry; instead of castling it had rules for entrenchment and pontoons. The Prussians adapted Helwig’s game to train their officers; the French learned the value of wargames the hard way in 1870. In 1913, when the Prussians were again rattling their sabers, the British writer H. G. Wells came up with a game called Little Wars, which was played on a tabletop, with miniature lead or tin soldiers. Then, in 1958, a fellow named Charles Roberts founded the Avalon Hill game company, and published a board game based on the battle of Gettysburg. Gettysburg and its successors were wildly popular; all over America, college students and other maladjusted types began to recreate, in their dorms and basements and family rooms, the great battles of history.

D&D gets its appetite for rules from wargames, which have been around for thousands of years. The modern war game began in the late eighteenth century, when a certain Helwig, the Master of Pages to the German Duke of Brunswick, invented something called “War Chess”: instead of rooks and knights and pawns it featured cavalry, artillery and infantry; instead of castling it had rules for entrenchment and pontoons. The Prussians adapted Helwig’s game to train their officers; the French learned the value of wargames the hard way in 1870. In 1913, when the Prussians were again rattling their sabers, the British writer H. G. Wells came up with a game called Little Wars, which was played on a tabletop, with miniature lead or tin soldiers. Then, in 1958, a fellow named Charles Roberts founded the Avalon Hill game company, and published a board game based on the battle of Gettysburg. Gettysburg and its successors were wildly popular; all over America, college students and other maladjusted types began to recreate, in their dorms and basements and family rooms, the great battles of history. If there were a point to life, the point would be pleasure. I knew a man, an Italian communist, who liked to say, raising a glass of champagne and nibbling a blini with caviar, “Nothing’s too good for the working class.” Kafka’s Hunger Artist explains to the overseer at the end of the story he’s not a saint, nor is he devoted to art or sacrifice. He’s just a picky eater. “I have to fast. I can’t help it … I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, believe me, I should have made no fuss and stuffed myself like you or anyone else.”

If there were a point to life, the point would be pleasure. I knew a man, an Italian communist, who liked to say, raising a glass of champagne and nibbling a blini with caviar, “Nothing’s too good for the working class.” Kafka’s Hunger Artist explains to the overseer at the end of the story he’s not a saint, nor is he devoted to art or sacrifice. He’s just a picky eater. “I have to fast. I can’t help it … I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, believe me, I should have made no fuss and stuffed myself like you or anyone else.” Over the last few decades, an idea called the critical brain hypothesis has been helping neuroscientists understand how the human brain operates as an information-processing powerhouse. It posits that the brain is always teetering between two phases, or modes, of activity: a random phase, where it is mostly inactive, and an ordered phase, where it is overactive and on the verge of a seizure. The hypothesis predicts that between these phases, at a sweet spot known as the critical point, the brain has a perfect balance of variety and structure and can produce the most complex and information-rich activity patterns. This state allows the brain to optimize multiple information processing tasks, from carrying out computations to transmitting and storing information, all at the same time.

Over the last few decades, an idea called the critical brain hypothesis has been helping neuroscientists understand how the human brain operates as an information-processing powerhouse. It posits that the brain is always teetering between two phases, or modes, of activity: a random phase, where it is mostly inactive, and an ordered phase, where it is overactive and on the verge of a seizure. The hypothesis predicts that between these phases, at a sweet spot known as the critical point, the brain has a perfect balance of variety and structure and can produce the most complex and information-rich activity patterns. This state allows the brain to optimize multiple information processing tasks, from carrying out computations to transmitting and storing information, all at the same time. In the fall of 2015, college campuses were engulfed by fires ignited in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri. This is not to say that college students had until then been quiet in the face of police violence against black Americans. Throughout the previous year, it had often been college students who hit the streets, blocked traffic, occupied the halls of justice and malls of America, disrupted political campaign rallies, and risked arrest to protest the torture and suffocation of Eric Garner, the abuse and death of Sandra Bland, the executions of Tamir Rice, Ezell Ford, Tanisha Anderson, Walter Scott, Tony Robinson, Freddie Gray, ad infinitum.

In the fall of 2015, college campuses were engulfed by fires ignited in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri. This is not to say that college students had until then been quiet in the face of police violence against black Americans. Throughout the previous year, it had often been college students who hit the streets, blocked traffic, occupied the halls of justice and malls of America, disrupted political campaign rallies, and risked arrest to protest the torture and suffocation of Eric Garner, the abuse and death of Sandra Bland, the executions of Tamir Rice, Ezell Ford, Tanisha Anderson, Walter Scott, Tony Robinson, Freddie Gray, ad infinitum. At first glance, the world of Peanuts was a highly legible one, populated by clearly labeled types. And yet the labels kept leading into uncertainty. Snoopy, for example, was “a beagle.” He also read War and Peace and owned a typewriter. Lucy was a “fussbudget”: she was one always, in some essential way. But what was it about her that was “fussbudget”? Was there a fussbudgetness in all her words and actions or only in some of them? With Pig-Pen, it was somehow even more fundamental. Pig-Pen was dirty

At first glance, the world of Peanuts was a highly legible one, populated by clearly labeled types. And yet the labels kept leading into uncertainty. Snoopy, for example, was “a beagle.” He also read War and Peace and owned a typewriter. Lucy was a “fussbudget”: she was one always, in some essential way. But what was it about her that was “fussbudget”? Was there a fussbudgetness in all her words and actions or only in some of them? With Pig-Pen, it was somehow even more fundamental. Pig-Pen was dirty  Google researchers have made an AI that can generate minutes-long musical pieces from text prompts, and can even transform a whistled or hummed melody into other instruments, similar to how

Google researchers have made an AI that can generate minutes-long musical pieces from text prompts, and can even transform a whistled or hummed melody into other instruments, similar to how  Epicurus’s distinctive feature is his insistence that pleasure is the source of all happiness and is the only truly good thing. Hence the modern use of “epicurean” to mean gourmand. But Epicurus was no debauched hedonist. He thought the greatest pleasure was ataraxia: a state of tranquility in which we are free from anxiety. This raises the suspicion of false advertising – freedom from anxiety may be nice, but few would say it is positively pleasurable.

Epicurus’s distinctive feature is his insistence that pleasure is the source of all happiness and is the only truly good thing. Hence the modern use of “epicurean” to mean gourmand. But Epicurus was no debauched hedonist. He thought the greatest pleasure was ataraxia: a state of tranquility in which we are free from anxiety. This raises the suspicion of false advertising – freedom from anxiety may be nice, but few would say it is positively pleasurable. VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, mutineer couturier and inexhaustible activist, had a genius for suturing extremes: rebellion and tradition, deconstruction and craft. Born Vivienne Isabel Swire in Cheshire, England, Westwood was a primary-school teacher for many years before she and her second husband, Malcolm McLaren, pioneered the styles, sounds, and attitudes that evolved into the movement known as punk. Her commitment to history and radical politics continued to infuse her work over her six-decade-long career, and when she died on December 29, age eighty-one, the world lost one of its last great iconoclasts. In the pages that follow, writer

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, mutineer couturier and inexhaustible activist, had a genius for suturing extremes: rebellion and tradition, deconstruction and craft. Born Vivienne Isabel Swire in Cheshire, England, Westwood was a primary-school teacher for many years before she and her second husband, Malcolm McLaren, pioneered the styles, sounds, and attitudes that evolved into the movement known as punk. Her commitment to history and radical politics continued to infuse her work over her six-decade-long career, and when she died on December 29, age eighty-one, the world lost one of its last great iconoclasts. In the pages that follow, writer  Táíwò is a fearless and original thinker and, at times, a polemical one. To be sure, Táíwò in his ferocious mode is often witty (one chapter is called “Decolonise This!”) and scores some tidy hits, though sometimes Táíwò lets his polemical gifts carry him too far. (“Here is the deal,” he writes, “the world, the so-called West or Global North, does not owe Africa”—overlooking the many obstacles to African development, such as heavy-handed interventions in African economies by Western-dominated entities like the World Bank, and subsidies to Western farmers that price out their African counterparts.) But Táíwò’s excesses should not overshadow his insights. These are especially on display in his less scathing moments, in which he comes not to destroy decolonization but to take it over, by channeling its liberationist energies in a more productive direction. The race-based account of writers such as Mills, Táíwò points out, is complicated by colonialism’s white subjects—the Irish, Québécois and Afrikaners, for example. Many discussions of colonialism in Africa also pass over in silence what Táíwò terms “the single outstanding colonial issue in the continent,” the occupation of Western Sahara, which has been ongoing since 1975, and which features an African aggressor, Morocco. The fact that most African borders were originally drawn by colonial powers is often cited as evidence of colonialism’s ongoing presence. Táíwò counters that countries such as Nigeria, Cameroon, South Sudan and Eritrea have redrawn national borders since the colonial period, suggesting that the continent’s current borders also reflect African influence.

Táíwò is a fearless and original thinker and, at times, a polemical one. To be sure, Táíwò in his ferocious mode is often witty (one chapter is called “Decolonise This!”) and scores some tidy hits, though sometimes Táíwò lets his polemical gifts carry him too far. (“Here is the deal,” he writes, “the world, the so-called West or Global North, does not owe Africa”—overlooking the many obstacles to African development, such as heavy-handed interventions in African economies by Western-dominated entities like the World Bank, and subsidies to Western farmers that price out their African counterparts.) But Táíwò’s excesses should not overshadow his insights. These are especially on display in his less scathing moments, in which he comes not to destroy decolonization but to take it over, by channeling its liberationist energies in a more productive direction. The race-based account of writers such as Mills, Táíwò points out, is complicated by colonialism’s white subjects—the Irish, Québécois and Afrikaners, for example. Many discussions of colonialism in Africa also pass over in silence what Táíwò terms “the single outstanding colonial issue in the continent,” the occupation of Western Sahara, which has been ongoing since 1975, and which features an African aggressor, Morocco. The fact that most African borders were originally drawn by colonial powers is often cited as evidence of colonialism’s ongoing presence. Táíwò counters that countries such as Nigeria, Cameroon, South Sudan and Eritrea have redrawn national borders since the colonial period, suggesting that the continent’s current borders also reflect African influence. According to the right, a specter is haunting the United States: the specter of critical race theory (CRT).

According to the right, a specter is haunting the United States: the specter of critical race theory (CRT). Every year, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) chooses the theme for

Every year, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) chooses the theme for