This looks like it could be an aerial photograph of the river Eisack as it runs through Franzensfeste, South Tyrol (see a real photo of that in the comments), but is actually just a tire-track in the snow in Franzensfeste with melting water in it.

Month: February 2023

The Rise of the Intellectual Influencer

by Mindy Clegg

I recently discovered a youtuber, Andy Stapleton. A former academic from a STEM field, his videos breakdown problems within academia and explores his perceptions of his failures in within that space. Although coming from a STEM field, his videos address academics across fields and he provides useful information for those within academia. But Stapleton is also a part of a new economic ecosystem that has grown up around the crises facing academics. As higher education continues to over-produce PhDs, many have sought to forge an alternative path that will allow them to continue in an intellectual stimulating professional life. This genre has become a new niche of the online info-tainment ecosystem. These intellectual influencers produce content for an audience that they hope will embrace and financially support their work.

Those who find themselves on the margins of the modern corporate university might find such an alternative attractive. But do we lose something in using social media to explore topics found in academia? Is it materially different from publishing books, journal articles, newspaper essays, or anything else that academics have done for years? Is it somehow less pure to fund intellectual pursuits via a combination of corporate or patreon sponsorships as opposed to from a university salary? The role of the public intellectual have been highly prized and being an intellectual influencer seems one such way to pursue that path. Where is the line between forging one’s own path and cynically trading knowledge for a paycheck (and is a university salary really any less fraught)? While we should interrogate how intellectually pursuits are funded, I argue that knowledge production is always historically situated. Much like art, there is no “pure” form of knowledge production, free of its historical context. Rather, knowledge production is shaped by the economic possibilities of the society in which it’s produced. Read more »

Seashore Rescue: A Seal Pup’s Journey from Abandonment to Independence

by David Greer

Camera in hand, nature photographer Myles Clarke walked along the pebble beach on South Pender Island watching for great blue herons, bald eagles, buffleheads, cormorants—any of the species likely to frequent waters close to the shore of a Salish Sea island on a summer’s day. He listened carefully for their familiar calls, but what he heard instead was plaintive cries unlike any bird’s, eerily like a child crying for its mother—“Ma-a-a! Ma-a-a!” Inexplicably, they seemed to be coming from the direction of a tiny islet in the bay, a hundred yards from shore, not the kind of place you’d expect to find a crying infant.

The source of the calls was indistinct against the black rock, so Myles pointed his 600 mm telephoto lens for a better look. What he saw was fascinating and unsettling. Three harbour seals were hauled out on the islet—a mother and her newborn side by side and, several feet away, a second pup, the source of the loud and piteous cries.

On return visits the next couple of days, Myles became increasingly concerned that the crying seal was in trouble. It seemed to approach mothers of other pups (there were several by now) as if attempting to suckle, and on each occasion the adult would chase the crying pup away and open its jaws as if threatening to bite. On the third day, the pup seemed to have become weaker and its cries fainter. Read more »

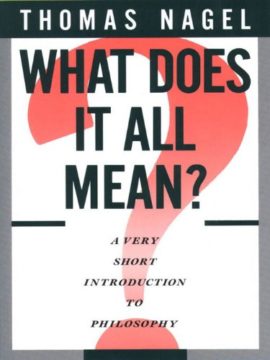

On Thomas Nagel’s “What Does It All Mean?”

Johnny Lyons in the Dublin Review of Books:

If asked by someone who is unfamiliar with philosophy what they might read to begin to grasp the subject, I would recommend Thomas Nagel’s What Does It All Mean? If pressed as to why this book rather than others, my response would proceed along the following lines.

If asked by someone who is unfamiliar with philosophy what they might read to begin to grasp the subject, I would recommend Thomas Nagel’s What Does It All Mean? If pressed as to why this book rather than others, my response would proceed along the following lines.

Philosophy is a fascinating and wickedly difficult subject. There are many who have tried to convey its interest but without doing justice to its complexity. Conversely, there are those who have sought to capture its intricacy but at the cost of losing sight of its vitality. Only a few have succeeded in giving an account of the subject that is both engaging to the newcomer and yet faithful to its difficulty, recognising that there’s no shallow end in the philosophical pool whilst providing beginners with enough buoyancy to keep their heads above water. Nagel’s concise primer (less than 25,000 words) stands proudly, even pre-eminently, among such select company.

More here.

California’s greatest poet wrote in Polish

Joe Mathews at the VC Star:

Want to become a signature voice of your nation? Try a decades-long exile in California.

Want to become a signature voice of your nation? Try a decades-long exile in California.

It worked for Czeslaw Milosz, who entered the pantheon of Polish poets thanks to works he wrote mostly in Berkeley.

The poet’s story — told by scholar Cynthia L. Haven in a thought-provoking book, “Czeslaw Milosz: A California Life” — demonstrates how our state allows people to move both further from and closer to home, often at the same time.

Milosz, while famous in Poland and among poets (Joseph Brodsky called him the greatest poet of our times), is unfamiliar to most Californians. But he remains the only faculty member of the University of California to win a Nobel Prize in literature.

“The irony,” writes Haven, “is that the greatest California poet — and certainly one of America’s greatest poets too — could well be a Pole who wrote a single poem in English.”

More here.

Salman Rushdie in conversation with David Remnick

Are everyday chemicals contributing to global obesity?

Anthony King in Chemistry World:

Obesity is on the rise almost everywhere, with more overweight and obese than underweight people, globally. According to accepted wisdom, blame lies squarely with overeating and insufficient exercise. A small group of researchers is challenging such ingrained assumptions, however, and shining a spotlight on the role of chemicals in our expanding waistlines.

Obesity is on the rise almost everywhere, with more overweight and obese than underweight people, globally. According to accepted wisdom, blame lies squarely with overeating and insufficient exercise. A small group of researchers is challenging such ingrained assumptions, however, and shining a spotlight on the role of chemicals in our expanding waistlines.

‘There are at least 50 chemicals, probably many more, that literally make us fatter,’ says Leonardo Trasande, an environmental health scientist at New York University in the US. An obesogen is a chemical that makes a living organism gain fat. Notable examples include bisphenol A, certain phthalates and most organophosphate flame retardants. They can push organisms to make new fat cells and/or encourage them to store more fat. Almost all of us often encounter such chemicals every day.

This may even help explain some discrepancies in data.

More here.

If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal – the problem with human intelligence

PD Smith in The Guardian:

Friedrich Nietzsche claimed that humankind was “a fantastic animal that has to fulfil one more condition of existence than any other animal”: we have to know why we exist. Justin Gregg, a researcher into animal behaviour and cognition, agrees, describing humankind as “the why specialists” of the natural world. Our need to know the reasons behind the things we see and feel distinguishes us from other animals, who make effective decisions without ever asking why the world is as it is.

Friedrich Nietzsche claimed that humankind was “a fantastic animal that has to fulfil one more condition of existence than any other animal”: we have to know why we exist. Justin Gregg, a researcher into animal behaviour and cognition, agrees, describing humankind as “the why specialists” of the natural world. Our need to know the reasons behind the things we see and feel distinguishes us from other animals, who make effective decisions without ever asking why the world is as it is.

Evidence of this unique aspect of our intelligence first appeared 44,000 years ago in cave paintings of half-human, half-animal figures, supernatural beings that suggest we were asking religious questions: “Why am I here? And why do I have to die?” Twenty-thousand years later, we began planting crops, revealing an awareness of cause and effect – an understanding of how seeds germinate and what to do to keep them alive. Ever since then, our constant questioning of natural phenomena has led to great discoveries, from astronomy to evolution.

But rather than being our crowning glory as a species, is it possible that human intelligence is in fact a liability, the source of our existential angst and increasingly apparent talent for self-destruction? This is the question Gregg sets out to answer in his entertaining and original book.

More here.

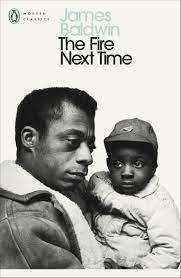

13 of Our Favorite Books On Black Resistance and Revolution

Damola Durosomo in Okay Africa:

This month at OkayAfrica, we’re celebrating Black revolution—icons and movements throughout history that have fostered revolutionary thinking and encouraged social progress. Black history is filled with an abundance of brave, era-defining artists, writers, politicians and more who’ve embodied a spirit of boldness and progressive thinking in the face of adversity. In today’s rocky political landscape of hate, misogyny and anti-blackness, these thinker’s teachings, words and ideas are invaluable. There’s no shortage of literature form the likes of Malcolm X to Steve Biko, Thomas Sankara and more that continue to spark fire in people and encourage a revolutionary spirit years after they were written. Below are 13 of our favorite books about black revolution.

This month at OkayAfrica, we’re celebrating Black revolution—icons and movements throughout history that have fostered revolutionary thinking and encouraged social progress. Black history is filled with an abundance of brave, era-defining artists, writers, politicians and more who’ve embodied a spirit of boldness and progressive thinking in the face of adversity. In today’s rocky political landscape of hate, misogyny and anti-blackness, these thinker’s teachings, words and ideas are invaluable. There’s no shortage of literature form the likes of Malcolm X to Steve Biko, Thomas Sankara and more that continue to spark fire in people and encourage a revolutionary spirit years after they were written. Below are 13 of our favorite books about black revolution.

1. The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

The prolific writer’s 1963 book, contains two thought-provoking essays: My Dungeon Shook—Letter to my Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of Emancipation, a gut-wrenching address to his young nephew about the perils of back identity in America and a meditation on intergenerational trauma, change and legacy, and Down At The Cross — Letter from a Region of My Mind is an equally poignant piece that chronicles his childhood experiences in Harlem. The essay offers a provocative stance on racial dynamics in America.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

Charlie Thomas (1937 – 2023) Singer

Burt Bacharach (1928 – 2023) Composer

Rosalyn Pope (1938 – 2023) Civil Rights Activist

Sunday Poem

The Lesson of the Sugarcane

My mother opened her eyes wide

at the edge of the field

ready for cutting.

“Take a deep breath,”

… she whispered,

“There is nothing as sweet:

Nada más dulce.”

… Overhearing,

Father left the flat he was changing

in the road-warping sun,

and, grabbing my arm, broke my sprint

toward the stalk:

“Cane can choke a little girl: snakes hide

where it grows over your head.”

And he led us back to the crippled car

where we sweated out our penitence,

for having craved more sweetness

then we were allowed,

more than we could handle.

by Judith Ortize Cofer

from Touching the Fire — Fifteen Poets of

Today’s Latino Renaissance

Anchor Books, 1998

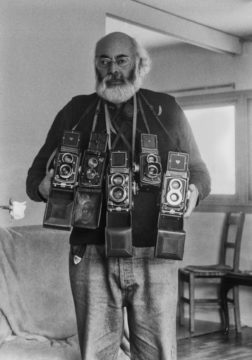

Beyond Borders

Adam Shatz on Adolfo Kaminsky in the LRB:

Adam Shatz on Adolfo Kaminsky in the LRB:

In the spring of 1944, a young man was stopped at a checkpoint of the Pétainist milice outside the Saint-Germain-des-Prés metro station. According to his identity card, he was Julien Keller, aged seventeen, a dyer, born in the département of the Creuse. The bag he was carrying contained dozens of other fake identity papers. But he was confident that the police had no idea how frightened he was because he had learned to affect an air of serenity. ‘I also knew, with certainty, that my papers were in order,’ he recalled many years later. After all, ‘I was the one who had made them.’

‘Julien Keller’ was the nom de guerre of Adolfo Kaminsky, who died in Paris last month aged 97. It was largely thanks to him that the German-occupied zone of wartime France was flooded with false documents. The Occupation authorities were on his trail, but they never suspected that the forger they were after was a teenager. (He was actually eighteen, but claimed to be a year younger to avoid conscription into the Compulsory Work Service.) Kaminsky worked out of a laboratory on the rue des Saints-Pères, disguised as an artist’s studio. Housed in a tiny attic, it belonged to the ‘6th’, a secret section of the General Union of Israelites of France (UGIF), an organisation the Vichy regime had set up and financed with money and property confiscated from Jews. The UGIF pretended to be a humanitarian outfit but would be instrumental in organising the deportation of the Jewish population. The network of the 6th set out to undermine its parent organisation, resisting the Occupation and forging links with various Resistance groups: communists, Zionists and supporters of Charles de Gaulle. Over the course of the war, the 6th helped to save as many as ten thousand Jews from deportation.

More here.

After Independence, Algeria Launched an Experiment in Self-Managing Socialism

Hall Greenland in Jacobin:

There is a famous concluding scene to Gillo Pontecorvo’s classic 1966 film The Battle of Algiers. After witnessing the French paratroopers “win” the battle by a combination of torture and murder over the previous hour and a half, the film climaxes with the residents of the Casbah surging out into the city with their rebel flags and banners blowing in the wind proclaiming independence and freedom for Algeria.

This was no sop to those of us who like a Hollywood-type happy ending but historical truth. Despite the rout in 1957 of the pro-independence Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) in the actual battle of Algiers, the people themselves went on organizing.

When the French president Charles de Gaulle made his visit to Algeria in December 1960, the people of Algiers and half a dozen other cities throughout the country exploded into mass manifestations to impress on him their unbreakable determination to be free.

It was not the last spontaneous intervention of ordinary Algerians in the fate of their country. When independence came in 1962, most of the million European settlers decided to emigrate rather than live under Algerian rule. They left the country bereft of doctors, engineers, technicians, and teachers.

They also left behind them a trail of destruction. It was not only the terrorist OAS (Secret Army Organization) which wreaked this vengeance, killing thousands of unarmed Algerians. Farmers and businessmen also destroyed machinery and wrecked buildings as they departed.

The abandonment and destruction of the settler farms meant that Algeria faced starvation as the settlers had appropriated the best land. In addition, the French counterinsurgency had forced more than two million Algerians off the land as vast swathes of the countryside were cleared of villages and farms for free-fire zones.

Into this impending famine stepped the hundreds of thousands of Algerian farm workers who took over the abandoned farms and managed them themselves.

More here.

The Carbon Triangle

Jeremy Wallace in The Polycrisis:

Jeremy Wallace in The Polycrisis:

China has ended zero-Covid. The resultant viral tsunami is crashing through China’s cities and countryside, causing hundreds of millions of infections and untold numbers of deaths. The reversal followed widespread protests against lockdown measures. But the protests were not the only cause—the country’s sagging economy also required attention. Outside of a few strong sectors, including EVs and renewable energy technologies, China’s economic dynamo was beginning to stutter in ways it had not in decades.

Whenever global demand or internal growth faltered in the recent past, China’s government would unleash pro-investment stimulus with impressive results. Vast expanses of highways, shiny airports, an enviable high-speed rail network, and especially apartments. In 2016, one estimate of planned new construction in Chinese cities could have housed 3.4 billion people. Those plans have been reined in, but what has been completed is still prodigious. Hundreds of millions of urbanizing Chinese have found shelter, and old buildings have been replaced with upgrades.

The scale of construction has been so prodigious, in fact, that it has far exceeded demand for housing. Tens of millions of apartments sit empty—almost as many homes as the US has constructed this century. Whole complexes of unfinished concrete shells sixteen stories tall surround most cities. Real estate, which constitutes a quarter of China’s GDP, has become a $52 trillion bubble that fundamentally rests on the foundational belief that it is too big to fail. The reality is that it has become too big to sustain, either economically or environmentally.

More here.

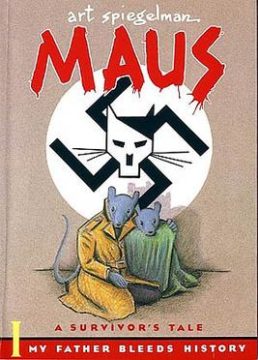

Maus Now

Rachel Cooke at The Guardian:

Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget.

Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget.

more here.

The Essential Colette

Sadie Stein at the NY Times:

Colette was not merely the most famous writer of her day, but one of the most famous people, period. A demimondaine with a shocking reputation, by the time of her death, in 1954, Colette was an institution, the first French woman of letters ever honored with a state funeral. (The church denied her a Catholic burial on the grounds of her multiple divorces.)

Colette was not merely the most famous writer of her day, but one of the most famous people, period. A demimondaine with a shocking reputation, by the time of her death, in 1954, Colette was an institution, the first French woman of letters ever honored with a state funeral. (The church denied her a Catholic burial on the grounds of her multiple divorces.)

By turns revolutionary and retrograde, liberated and conservative, a traditionalist who defied labels and loved a title, Colette was nothing if not contradictory. Both her life (81 years long) and her body of work (which exceeded 40 books) were epic, and given that her writing was so often autobiographical, the two were inextricably conflated in the public mind. But if anything, her notoriety obscured the greatness of her prose: Her event-filled life often overshadowed the accomplishments of her best-selling fiction.

more here.

A Free Spirit And A Fearless Artist: Colette At 150

‘Breasts and Eggs’ Made Her a Feminist Icon. She Has Other Ambitions

Joshua Hunt in The New York Times:

On the last Friday in November, in the afterglow of a literary awards ceremony, the novelist Mieko Kawakami held court in a banquet hall at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, wearing a tweed Gucci dress, clutching an Hermès Birkin handbag and sipping a glass of domestic beer she would never quite finish. Each time she raised the drink to her lips, another writer, editor or publicist came along to distract her from it. Kawakami, who is 46, greeted them each with a degree of warmth that made it hard to tell which were strangers and which were her friends. “I’m a graduate of hostess university,” she said, recalling her years spent working at a bar where she kept men company as they drank. More than two decades later, the skills she honed in the boozy, neon-lit back alleys of Osaka — the ability to observe and to listen with acute curiosity — are still apparent in her best-selling novels. “You can see where that sensitivity arises from in her work,” the translator David Boyd told me. “She sees all the angles.”

On the last Friday in November, in the afterglow of a literary awards ceremony, the novelist Mieko Kawakami held court in a banquet hall at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, wearing a tweed Gucci dress, clutching an Hermès Birkin handbag and sipping a glass of domestic beer she would never quite finish. Each time she raised the drink to her lips, another writer, editor or publicist came along to distract her from it. Kawakami, who is 46, greeted them each with a degree of warmth that made it hard to tell which were strangers and which were her friends. “I’m a graduate of hostess university,” she said, recalling her years spent working at a bar where she kept men company as they drank. More than two decades later, the skills she honed in the boozy, neon-lit back alleys of Osaka — the ability to observe and to listen with acute curiosity — are still apparent in her best-selling novels. “You can see where that sensitivity arises from in her work,” the translator David Boyd told me. “She sees all the angles.”

The awards ceremony was hosted by Shueisha, a major Japanese publishing house that recruited Kawakami as a judge, confirming her as an arbiter of taste. “One of the reasons my boss pleaded and pleaded for Kawakami-san to judge for our prize is because of her fame and her popularity among young Japanese writers,” said Yuki Kishi, a literary editor at Shueisha. In the time since Kawakami acquiesced to that role, more women had submitted unpublished manuscripts for consideration, Kishi told me, and more of them took risks concerning voice and content. “A lot of people look up to Kawakami-san’s writing and her style and her energy and her buntai (literary style),” Kishi said as we left the banquet hall. “We want to be her.” What Kawakami wants, however, is to confound expectations by writing books that are at times provocatively against type, as if to prove that there is no category that can contain her.

“I’m not an Olympic athlete,” she told me. “Literature doesn’t represent anything.”

More here.