Katherine Irving in The Scientist:

In 1909, a chicken breeder approached Rockefeller Institute pathologist Peyton Rous with one of her hens. The chicken had a large, malignant tumor growing from the connective tissue in its breast, and Rous, who had long been fascinated by tumor biology and transmissibility, decided to investigate. He took biopsies and ground up the samples, then passed them through filters to remove any cells. Finally, he injected the mixture into healthy chickens of the same breed and watched as these chickens developed tumors of their own. This was to become the first major result that solid tumors can be infectious and spread through what some researchers at the time called “filterable agents,” now better known as viruses, which weren’t described in detail until the discovery of the electron microscope decades later.

In 1909, a chicken breeder approached Rockefeller Institute pathologist Peyton Rous with one of her hens. The chicken had a large, malignant tumor growing from the connective tissue in its breast, and Rous, who had long been fascinated by tumor biology and transmissibility, decided to investigate. He took biopsies and ground up the samples, then passed them through filters to remove any cells. Finally, he injected the mixture into healthy chickens of the same breed and watched as these chickens developed tumors of their own. This was to become the first major result that solid tumors can be infectious and spread through what some researchers at the time called “filterable agents,” now better known as viruses, which weren’t described in detail until the discovery of the electron microscope decades later.

These findings would eventually change the course of cancer research, but when Rous first reported his discoveries in 1910 and 1911, the scientific community was underwhelmed, according to Scripps Research cancer biologist Peter Vogt. “Rous made this big discovery, and at the time it was incredibly ahead of the field,” says Vogt, who coauthored a perspective piece on the virus, later named Rous sarcoma virus, or RSV (not to be confused with respiratory syncytial virus, also abbreviated to RSV). “People either didn’t believe him or belittled his work.”

More here.

I’m not Michel Foucault, but here’s a history of sexuality, greatly abridged: First came the slut shamers. The traditionalist, patriarchal religious haranguers. Things weren’t great for men in the before times, but they were particularly unpleasant for women. Then came the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, which involved chucking all the rules. This had some good effects (ambitious women at last permitted to leave their houses and become doctors, lawyers, bosses) and some less good ones (moviemakers permitted to assault underage girls). In the 1990s and early 2000s, following however many backlashes against backlashes, the sexual revolution re-emerged as sex positivity.

I’m not Michel Foucault, but here’s a history of sexuality, greatly abridged: First came the slut shamers. The traditionalist, patriarchal religious haranguers. Things weren’t great for men in the before times, but they were particularly unpleasant for women. Then came the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, which involved chucking all the rules. This had some good effects (ambitious women at last permitted to leave their houses and become doctors, lawyers, bosses) and some less good ones (moviemakers permitted to assault underage girls). In the 1990s and early 2000s, following however many backlashes against backlashes, the sexual revolution re-emerged as sex positivity. SOMETIME THIS COMING

SOMETIME THIS COMING One name you don’t hear a lot these days is Thomas Piketty. In 2013, the French economist burst into the popular consciousness with the publication of

One name you don’t hear a lot these days is Thomas Piketty. In 2013, the French economist burst into the popular consciousness with the publication of

The invisibility of the disaster presents a serious difficulty to the filmmakers, who need their viewers to perceive it as the expert does. Their ingenious solution is found in the technical disaster movie’s pronounced ambience: the bustled score and sweaty palettes of Contagion; Chernobyl’s ghostly clanks and drones; the blare of Bloomberg terminals and pristine skylines of Margin Call. Through these effects, viewers are invited to pretend we know things we manifestly do not. We work through the night with Sullivan as he discovers his financial firm’s impending demise, study his stubbled face as he looks up from his illegible scrawl of equations before a pulsing monotone—and we simply know he’s uncovered something. The camera of Contagion fixates upon “fomites” (common objects that facilitate disease transmission), such that we learn to almost see viruses slithering over bus handles, glassware and casino chips. Chernobyl represents the presence of radiation with the throaty static of dosimeters (audible radiological instruments) that is often so loud and unnerving we forget we don’t exactly know what the sound means. Technical knowledge becomes an artificial sensorium, a collage of abstractions forced onto the nerve endings, always attempting to compensate for its baselessness.

The invisibility of the disaster presents a serious difficulty to the filmmakers, who need their viewers to perceive it as the expert does. Their ingenious solution is found in the technical disaster movie’s pronounced ambience: the bustled score and sweaty palettes of Contagion; Chernobyl’s ghostly clanks and drones; the blare of Bloomberg terminals and pristine skylines of Margin Call. Through these effects, viewers are invited to pretend we know things we manifestly do not. We work through the night with Sullivan as he discovers his financial firm’s impending demise, study his stubbled face as he looks up from his illegible scrawl of equations before a pulsing monotone—and we simply know he’s uncovered something. The camera of Contagion fixates upon “fomites” (common objects that facilitate disease transmission), such that we learn to almost see viruses slithering over bus handles, glassware and casino chips. Chernobyl represents the presence of radiation with the throaty static of dosimeters (audible radiological instruments) that is often so loud and unnerving we forget we don’t exactly know what the sound means. Technical knowledge becomes an artificial sensorium, a collage of abstractions forced onto the nerve endings, always attempting to compensate for its baselessness. Awe can mean many things. It can be witnessing a total solar eclipse. Or seeing your child take her first steps. Or hearing Lizzo perform live. But, while many of us know it when we feel it, awe is not easy to define. “Awe is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world,” said Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Awe can mean many things. It can be witnessing a total solar eclipse. Or seeing your child take her first steps. Or hearing Lizzo perform live. But, while many of us know it when we feel it, awe is not easy to define. “Awe is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world,” said Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. To learn to socialize, zebrafish need to trust their gut. Gut microbes encourage specialized cells to prune back extra connections in brain circuits that control social behavior, new University of Oregon research in zebrafish shows. The pruning is essential for the development of normal social behavior.

To learn to socialize, zebrafish need to trust their gut. Gut microbes encourage specialized cells to prune back extra connections in brain circuits that control social behavior, new University of Oregon research in zebrafish shows. The pruning is essential for the development of normal social behavior. Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

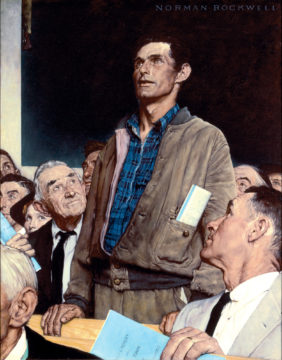

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

In 2022, I worked harder than before to keep my students’ tables free of smartphones. That this is a matter for negotiation at all, is because on the surface, the devices do so many things, and students often make a reasonable, possibly-good-faith case for using it for a specific purpose. I forgot my calculator; can I use my phone? No, thank you for asking, but you won’t be needing a calculator; just start with this exercise here, and don’t forget to simplify your fractions. Can I listen to music while I work? Yeah, uhm, no, I happen to be a big believer in collaborative work, I guess. Can I check my solutions online please? Ah, very good; but instead, use this printout that I bring to every one of your classes these days. I’m done, can I quickly look up my French homework? That’s a tough one, but no; it’s seven minutes to the bell anyway and I prepared a small Kahoot quiz on today’s topic. (So everyone please get your phones out.)

In 2022, I worked harder than before to keep my students’ tables free of smartphones. That this is a matter for negotiation at all, is because on the surface, the devices do so many things, and students often make a reasonable, possibly-good-faith case for using it for a specific purpose. I forgot my calculator; can I use my phone? No, thank you for asking, but you won’t be needing a calculator; just start with this exercise here, and don’t forget to simplify your fractions. Can I listen to music while I work? Yeah, uhm, no, I happen to be a big believer in collaborative work, I guess. Can I check my solutions online please? Ah, very good; but instead, use this printout that I bring to every one of your classes these days. I’m done, can I quickly look up my French homework? That’s a tough one, but no; it’s seven minutes to the bell anyway and I prepared a small Kahoot quiz on today’s topic. (So everyone please get your phones out.) Lita Albuquerque. Southern Cross, 2014, from Stellar Axis: Antarctica, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, 2006.

Lita Albuquerque. Southern Cross, 2014, from Stellar Axis: Antarctica, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, 2006.

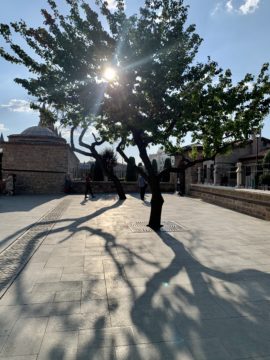

A tree in the vicinity of Rumi’s tomb has me transfixed. It isn’t the tree, actually, it is the force of attraction between tree-branch and sun-ray that seems to lift the tree off the ground and swirl it in sunshine, casting filigreed shadows on the concrete tiles across the courtyard. The tree’s heavenward reach is so magnificent that not only does it seem to clasp the sun but it spreads a tranquil yet powerful energy far beyond itself. It is easy to forget that the tree is small. I consider this my first meeting with Shams.

A tree in the vicinity of Rumi’s tomb has me transfixed. It isn’t the tree, actually, it is the force of attraction between tree-branch and sun-ray that seems to lift the tree off the ground and swirl it in sunshine, casting filigreed shadows on the concrete tiles across the courtyard. The tree’s heavenward reach is so magnificent that not only does it seem to clasp the sun but it spreads a tranquil yet powerful energy far beyond itself. It is easy to forget that the tree is small. I consider this my first meeting with Shams.