Natalie So at The Believer:

In the early ’90s, the FBI had learned of a Vietnamese-Chinese heroin organization that was closely aligned with Vietnamese street gangs throughout the United States. Their connections were wide-ranging, and they were loosely affiliated with the Triads (including Frank Ma, one of the last Chinese “godfathers” in New York), as well as with several other high-echelon Asian crime bosses in various American cities. But this heroin organization operated differently from the Asian gangs of previous generations.

In the early ’90s, the FBI had learned of a Vietnamese-Chinese heroin organization that was closely aligned with Vietnamese street gangs throughout the United States. Their connections were wide-ranging, and they were loosely affiliated with the Triads (including Frank Ma, one of the last Chinese “godfathers” in New York), as well as with several other high-echelon Asian crime bosses in various American cities. But this heroin organization operated differently from the Asian gangs of previous generations.

First, they relied on two key pieces of technology: the cellular phone and the pager. They were financially and technologically savvy, and instead of being tied to one specific location, they operated a national network, with cells and confederates in various cities.

more here.

Jünger’s politics were complicated, if not incoherent. A decorated veteran of the First World War (he made his literary debut with a bellicose, best-selling diary from the trenches, Storm of Steel) who was praised by Hitler but who refused to join the Nazi Party; a self-taught conservative intellectual (Jünger never completed university) who won the admiration of Marxist writers like Bertolt Brecht; an incurable elitist sympathetic to communist centralization (he opposed liberalism above all)—the Weimar-era Jünger projected an aloof, aestheticizing, and ultimately paradoxical strain of fascism. Kracauer captured what feels most damning about Jünger’s political thinking during this time in a review of his controversial treatise The Worker (1932) for the Frankfurter Zeitung, in which he accused Jünger of having “metaphysicized” (metaphysiziert) politics: What about real, tangible action in our own historical moment? Metaphysics is an escape.

Jünger’s politics were complicated, if not incoherent. A decorated veteran of the First World War (he made his literary debut with a bellicose, best-selling diary from the trenches, Storm of Steel) who was praised by Hitler but who refused to join the Nazi Party; a self-taught conservative intellectual (Jünger never completed university) who won the admiration of Marxist writers like Bertolt Brecht; an incurable elitist sympathetic to communist centralization (he opposed liberalism above all)—the Weimar-era Jünger projected an aloof, aestheticizing, and ultimately paradoxical strain of fascism. Kracauer captured what feels most damning about Jünger’s political thinking during this time in a review of his controversial treatise The Worker (1932) for the Frankfurter Zeitung, in which he accused Jünger of having “metaphysicized” (metaphysiziert) politics: What about real, tangible action in our own historical moment? Metaphysics is an escape. This year marks the centenary of modernism’s annus mirabilis. For many, that means T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses—both first published in book form in 1922—perhaps along with the first English language translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. These books are in different genres and disciplines—poetry, fiction, philosophy—but all of them wed experimental literary aesthetics with highly abstract intellectual projects. All invoke myths to represent immense aesthetic and intellectual challenges: each tells of an arduous journey, that could, if successful, be redemptive, even transformative. Each text has its hero, but in each case the hero is also—or really—you. You, the reader, are challenged to find your way through these depths and heights and broad, rough seas. The journey is perilous, filled with traps as well as marvels. Should you succeed, your home may look different by the end; you will be changed too.

This year marks the centenary of modernism’s annus mirabilis. For many, that means T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses—both first published in book form in 1922—perhaps along with the first English language translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. These books are in different genres and disciplines—poetry, fiction, philosophy—but all of them wed experimental literary aesthetics with highly abstract intellectual projects. All invoke myths to represent immense aesthetic and intellectual challenges: each tells of an arduous journey, that could, if successful, be redemptive, even transformative. Each text has its hero, but in each case the hero is also—or really—you. You, the reader, are challenged to find your way through these depths and heights and broad, rough seas. The journey is perilous, filled with traps as well as marvels. Should you succeed, your home may look different by the end; you will be changed too. Life is rich with moments of uncertainty, where we’re not exactly sure what’s going to happen next. We often find ourselves in situations where we have to choose between different kinds of uncertainty; maybe one option is very likely to have a “pretty good” outcome, while another has some probability for “great” and some for “truly awful.” In such circumstances, what’s the rational way to choose? Is it rational to go to great lengths to avoid choices where the worst outcome is very bad? Lara Buchak argues that it is, thereby expanding and generalizing the usual rules of rational choice in conditions of risk.

Life is rich with moments of uncertainty, where we’re not exactly sure what’s going to happen next. We often find ourselves in situations where we have to choose between different kinds of uncertainty; maybe one option is very likely to have a “pretty good” outcome, while another has some probability for “great” and some for “truly awful.” In such circumstances, what’s the rational way to choose? Is it rational to go to great lengths to avoid choices where the worst outcome is very bad? Lara Buchak argues that it is, thereby expanding and generalizing the usual rules of rational choice in conditions of risk. H.G. Wells once predicted that “statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write.” It was a slight exaggeration, but in an age of big data in which governments pride themselves on being “evidence-based” and “guided by the science,” an understanding of where facts and figures come from is important if you want to think clearly.

H.G. Wells once predicted that “statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write.” It was a slight exaggeration, but in an age of big data in which governments pride themselves on being “evidence-based” and “guided by the science,” an understanding of where facts and figures come from is important if you want to think clearly. On Tuesday, the Department of Energy is expected to announce a breakthrough

On Tuesday, the Department of Energy is expected to announce a breakthrough  In the

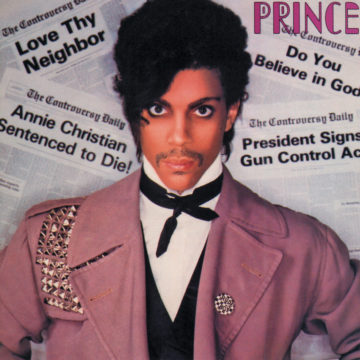

In the  PINUPS ARE RUMORED TO EMERGE FROM THE SEA, mer-peoples caught between nautical and earthly existence, so that maybe there are fewer black pinups circulating in popular culture, because the sea for us is in part the graveyard of the Middle Passage, not just an escapist fantasy. Black pinups would emerge blood-drenched and haunting, rather than seducing onlookers. Just bypass the trance of glamour and observe Josephine Baker’s double consciousness in any photograph, at once entertaining you and devastating you, silly and caustic with grief. Or just look at Prince and try not to fall in love. Hilton Als’s account of witnessing, meeting, interviewing, befriending, and loving Prince Rogers Nelson begins with the recapitulation of a Jamie Foxx stand-up bit, in which Foxx describes involuntarily lusting after Prince at first glance, I mean he’s cute, he’s pretty. Foxx sits with the ambiguity onstage, seeming to need the confessional; it’s the frantic announcement of a romance that’s been a secret for too long. He’s not just aroused when he looks into and avoids Prince’s eyes during their conversation, he’s overcome and forever changed. Prince is loved, lusted after, and objectified like a pinup because his presence and his music compel us to overcome ourselves. His is the kind of irreducible androgyny that upends gender without the use of any jargon—it’s God-driven wish-fulfillment.

PINUPS ARE RUMORED TO EMERGE FROM THE SEA, mer-peoples caught between nautical and earthly existence, so that maybe there are fewer black pinups circulating in popular culture, because the sea for us is in part the graveyard of the Middle Passage, not just an escapist fantasy. Black pinups would emerge blood-drenched and haunting, rather than seducing onlookers. Just bypass the trance of glamour and observe Josephine Baker’s double consciousness in any photograph, at once entertaining you and devastating you, silly and caustic with grief. Or just look at Prince and try not to fall in love. Hilton Als’s account of witnessing, meeting, interviewing, befriending, and loving Prince Rogers Nelson begins with the recapitulation of a Jamie Foxx stand-up bit, in which Foxx describes involuntarily lusting after Prince at first glance, I mean he’s cute, he’s pretty. Foxx sits with the ambiguity onstage, seeming to need the confessional; it’s the frantic announcement of a romance that’s been a secret for too long. He’s not just aroused when he looks into and avoids Prince’s eyes during their conversation, he’s overcome and forever changed. Prince is loved, lusted after, and objectified like a pinup because his presence and his music compel us to overcome ourselves. His is the kind of irreducible androgyny that upends gender without the use of any jargon—it’s God-driven wish-fulfillment. O

O When the Italian writer and publisher Roberto Calasso died last year, he was more widely admired than understood. When he is praised in the Anglophone world, it is usually for being erudite. Meanwhile, in his native Italy, Calasso is better known as a publishing impresario, because of his leadership of the independent publishing house Adelphi. Calasso’s great work, a capacious 11-part series that he began in 1983 with The Ruin of Kasch, and ended in 2021 with The Tablet of Destinies, is often said to be indescribable. Actually, it is rather straightforward once you have the key. Calasso is writing gnoseology (a word he uses often)—that is, an examination and history of esoteric knowledge.

When the Italian writer and publisher Roberto Calasso died last year, he was more widely admired than understood. When he is praised in the Anglophone world, it is usually for being erudite. Meanwhile, in his native Italy, Calasso is better known as a publishing impresario, because of his leadership of the independent publishing house Adelphi. Calasso’s great work, a capacious 11-part series that he began in 1983 with The Ruin of Kasch, and ended in 2021 with The Tablet of Destinies, is often said to be indescribable. Actually, it is rather straightforward once you have the key. Calasso is writing gnoseology (a word he uses often)—that is, an examination and history of esoteric knowledge. Decades of work and billions of dollars went into funding clinical trials of dozens of drug compounds that targeted amyloid plaques. Yet almost none of the trials showed meaningful benefits to patients with the disease.

Decades of work and billions of dollars went into funding clinical trials of dozens of drug compounds that targeted amyloid plaques. Yet almost none of the trials showed meaningful benefits to patients with the disease. For the past 12 weeks, revolutionary sentiment has been coursing through the cities and towns of the Persian plateau. The agitation was triggered by the

For the past 12 weeks, revolutionary sentiment has been coursing through the cities and towns of the Persian plateau. The agitation was triggered by the  Bell’s palsy is a neurological condition resulting from damage to the seventh cranial nerve, and typified by partial facial paralysis and pain on one side of the head.

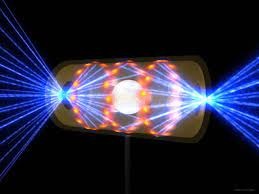

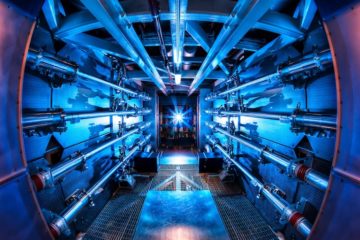

Bell’s palsy is a neurological condition resulting from damage to the seventh cranial nerve, and typified by partial facial paralysis and pain on one side of the head. Existing nuclear power plants work through fission — splitting apart heavy atoms to create energy. In fission, a neutron collides with a heavy uranium atom, splitting it into lighter atoms and releasing a lot of heat and energy at the same time. Fusion, on the other hand, works in the opposite way — it involves smushing two atoms (often two hydrogen atoms) together to create a new element (often helium), in the same way that stars creates energy. In that process, the two hydrogen atoms lose a small amount of mass, which is converted to energy according to Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc². Because the speed of light is very, very fast — 300,000,000 meters per second — even a tiny amount of mass lost can result in a ton of energy.

Existing nuclear power plants work through fission — splitting apart heavy atoms to create energy. In fission, a neutron collides with a heavy uranium atom, splitting it into lighter atoms and releasing a lot of heat and energy at the same time. Fusion, on the other hand, works in the opposite way — it involves smushing two atoms (often two hydrogen atoms) together to create a new element (often helium), in the same way that stars creates energy. In that process, the two hydrogen atoms lose a small amount of mass, which is converted to energy according to Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc². Because the speed of light is very, very fast — 300,000,000 meters per second — even a tiny amount of mass lost can result in a ton of energy.