Carrie Battan at The New Yorker:

The Spanish pop star Rosalía is the rarest kind of modern musician: a relentlessly innovative aesthetic omnivore who also happens to have a decade of Old World, genre-specific formal training under her belt. As a teen-ager living on the outskirts of Barcelona, she was introduced to flamenco music by a group of friends from Andalusia, a region in the south of Spain where the style originated. Hearing the music of the flamenco giant Camarón de la Isla, she once told El Mundo, made her feel as if her “head exploded.” The discovery prompted Rosalía to throw her entire being into the practice of flamenco, an elemental genre built around hand-clapping, acoustic guitar, and a fierce and improvisational vocal style. She took flamenco dance classes; she learned guitar and piano, and, most important, she enrolled at the Catalonia College of Music, under the tutelage of the decorated flamenco singer and teacher Chiqui de la Línea. Pioneered by the Romani people (the term for Spain’s Gypsy population), the vocals of traditional flamenco are like kites—they follow unpredictable and precarious paths but sound as if they’re being buoyed by an invisible force of nature. Rosalía did not merely train to become a singer; she strove to master the intense and distinctive styles of flamenco’s beloved cantaores and cantaoras.

The Spanish pop star Rosalía is the rarest kind of modern musician: a relentlessly innovative aesthetic omnivore who also happens to have a decade of Old World, genre-specific formal training under her belt. As a teen-ager living on the outskirts of Barcelona, she was introduced to flamenco music by a group of friends from Andalusia, a region in the south of Spain where the style originated. Hearing the music of the flamenco giant Camarón de la Isla, she once told El Mundo, made her feel as if her “head exploded.” The discovery prompted Rosalía to throw her entire being into the practice of flamenco, an elemental genre built around hand-clapping, acoustic guitar, and a fierce and improvisational vocal style. She took flamenco dance classes; she learned guitar and piano, and, most important, she enrolled at the Catalonia College of Music, under the tutelage of the decorated flamenco singer and teacher Chiqui de la Línea. Pioneered by the Romani people (the term for Spain’s Gypsy population), the vocals of traditional flamenco are like kites—they follow unpredictable and precarious paths but sound as if they’re being buoyed by an invisible force of nature. Rosalía did not merely train to become a singer; she strove to master the intense and distinctive styles of flamenco’s beloved cantaores and cantaoras.

more here.

The President and the Provost have both been urging a whitewashing (if I can use this term) of the College’s history by such measures as removing Huxley’s name and bust from one of Imperial’s most prominent buildings. As I explained earlier, they attempted to accomplish this using a deeply flawed process. A History Group lacking in any higher level expertise in Huxley’s own areas of biology and palaeontology was set up, with the College archivist restricted to a consultative role, as was the Imperial faculty member best qualified to comment on historical matters. Two outside historians were consulted, but their areas of expertise did not really include Huxley.1 Adrian Desmond, Huxley’s biographer, was consulted but as I documented in my earlier article, his unambiguous vindication of Huxley was completely ignored. In October (revised version November), the

The President and the Provost have both been urging a whitewashing (if I can use this term) of the College’s history by such measures as removing Huxley’s name and bust from one of Imperial’s most prominent buildings. As I explained earlier, they attempted to accomplish this using a deeply flawed process. A History Group lacking in any higher level expertise in Huxley’s own areas of biology and palaeontology was set up, with the College archivist restricted to a consultative role, as was the Imperial faculty member best qualified to comment on historical matters. Two outside historians were consulted, but their areas of expertise did not really include Huxley.1 Adrian Desmond, Huxley’s biographer, was consulted but as I documented in my earlier article, his unambiguous vindication of Huxley was completely ignored. In October (revised version November), the  I am a modern-day scrapbooker. Which is to say that, like scrapbookers and notebook keepers across the ages, I am incessantly recording: things I have read, things I want to read, ideas I have come across or had, ways I want to be or to look, memorabilia from places I have been or want to go, inspiring or thought-provoking words, song lyrics, images, film clips, you name it. Like those who went before me, I record things in physical notebooks, but – and this is the new thing – my canvas is far larger than this original form. Digital photo albums, the iPhone ‘notes’ pad, emails to self,

I am a modern-day scrapbooker. Which is to say that, like scrapbookers and notebook keepers across the ages, I am incessantly recording: things I have read, things I want to read, ideas I have come across or had, ways I want to be or to look, memorabilia from places I have been or want to go, inspiring or thought-provoking words, song lyrics, images, film clips, you name it. Like those who went before me, I record things in physical notebooks, but – and this is the new thing – my canvas is far larger than this original form. Digital photo albums, the iPhone ‘notes’ pad, emails to self,

I used to sit in class with songs in my head, loud enough to feel their beat in my fingertips. I used to blare Adele instead of listening to my teacher. I would sing voicelessly with Hozier while my classmates read a paragraph out loud. Passenger, P!nk, The Lumineers, Steven Sondheim. Billie Eilish, too, though not openly as it’s not cool to like anything that’s cool.

I used to sit in class with songs in my head, loud enough to feel their beat in my fingertips. I used to blare Adele instead of listening to my teacher. I would sing voicelessly with Hozier while my classmates read a paragraph out loud. Passenger, P!nk, The Lumineers, Steven Sondheim. Billie Eilish, too, though not openly as it’s not cool to like anything that’s cool. Daniel Everett’s 2008 book Don’t Sleep: There are Snakes tells two stories of loss. First, it tells how the young missionary linguist, who had been trained to analyse languages at the Summer Institute (now

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book Don’t Sleep: There are Snakes tells two stories of loss. First, it tells how the young missionary linguist, who had been trained to analyse languages at the Summer Institute (now

Most of us were in deep admiration of my DSE colleague Sukhamoy Chakravarty (I used to call him Sukhamoy-da). He was a prodigious scholar, a voracious reader of books (when discussing a book it was not unusual for him to point out to us that the author had slightly changed his position on an issue in question in the third edition in a long footnote), a man of wide intellectual interests, but also a man of charming simplicity and other-worldliness. In my period at DSE as he was mostly in the Planning Commission, I’d occasionally meet him at his home (or at Mrinal’s) in the evenings. I remember one evening I was discussing something with him in his living room, while a whole army of children (his daughter and her neighborhood friends) were enthusiastically carrying books, shifting them from one room to another corner of the house under the general supervision of his wife, Lalita (his partner and fellow economist since their Presidency College days). At one point he digressed from what we were discussing, and pointed to the army of load-carrying children, and said, “You see this is how the Industrial Revolution came about, on the backs of child labor”.

Most of us were in deep admiration of my DSE colleague Sukhamoy Chakravarty (I used to call him Sukhamoy-da). He was a prodigious scholar, a voracious reader of books (when discussing a book it was not unusual for him to point out to us that the author had slightly changed his position on an issue in question in the third edition in a long footnote), a man of wide intellectual interests, but also a man of charming simplicity and other-worldliness. In my period at DSE as he was mostly in the Planning Commission, I’d occasionally meet him at his home (or at Mrinal’s) in the evenings. I remember one evening I was discussing something with him in his living room, while a whole army of children (his daughter and her neighborhood friends) were enthusiastically carrying books, shifting them from one room to another corner of the house under the general supervision of his wife, Lalita (his partner and fellow economist since their Presidency College days). At one point he digressed from what we were discussing, and pointed to the army of load-carrying children, and said, “You see this is how the Industrial Revolution came about, on the backs of child labor”. A

A When we experience shame, we feel bad; and when we inflict shame, we feel good. Those seem to be among the few points of consensus when it comes to what the historian Peter N. Stearns calls a “disputed emotion.” Unlike fear or anger, shame is “self-conscious”; it doesn’t erupt so much as coil around itself. It requires an awareness of others and their disapproval, and it has to be learned. Aristotle thought of it as fundamental to ethical behavior; Confucius saw it as essential to social order.

When we experience shame, we feel bad; and when we inflict shame, we feel good. Those seem to be among the few points of consensus when it comes to what the historian Peter N. Stearns calls a “disputed emotion.” Unlike fear or anger, shame is “self-conscious”; it doesn’t erupt so much as coil around itself. It requires an awareness of others and their disapproval, and it has to be learned. Aristotle thought of it as fundamental to ethical behavior; Confucius saw it as essential to social order. When did it become as hard to imagine what a good—or at least not as bad—internet might look like as to picture a world without the internet at all? Social-media mobs, conspiratorial thinking, deadly disinformation campaigns, gadget addiction, the funk of mass attention-deficit disorder: World-Wide-Web woes comprise a growth economy. The less acute but vague unease of our encounter with digital technology isn’t much alleviated by the possibility of imagining a truly off-the-grid alternative. (That a bit of shorthand like “off the grid” exists to describe a break from tech is as much a symptom of the problem as anything.) Perhaps to say that we feel backed into a corner by a claque of devices of our own making is not really to say much of anything at all.

When did it become as hard to imagine what a good—or at least not as bad—internet might look like as to picture a world without the internet at all? Social-media mobs, conspiratorial thinking, deadly disinformation campaigns, gadget addiction, the funk of mass attention-deficit disorder: World-Wide-Web woes comprise a growth economy. The less acute but vague unease of our encounter with digital technology isn’t much alleviated by the possibility of imagining a truly off-the-grid alternative. (That a bit of shorthand like “off the grid” exists to describe a break from tech is as much a symptom of the problem as anything.) Perhaps to say that we feel backed into a corner by a claque of devices of our own making is not really to say much of anything at all. Even after vaccination,

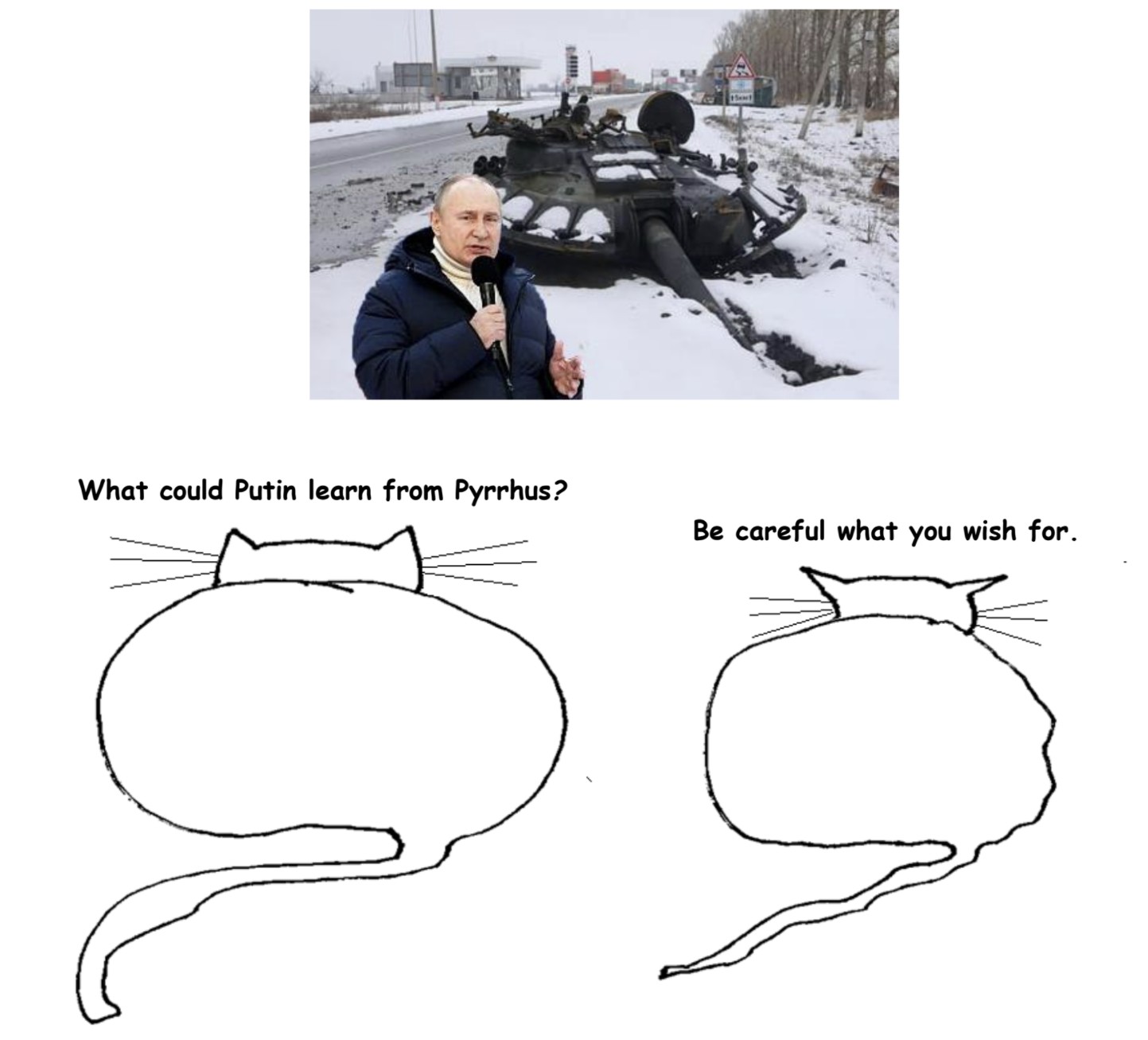

Even after vaccination,  The Russian invasion of Ukraine and ongoing responses by the global community have prompted renewed scrutiny of glaring energy and resource security gaps in the post-Cold War era. War, of course, is not new, nor is Russia’s aggression a unique threat to global energy security or decarbonization. However, as a nuclear-armed and energy export-intensive state engaged in an unprovoked attack on a neighboring country, Russia’s actions do pose novel challenges to national energy, security, and climate priorities.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and ongoing responses by the global community have prompted renewed scrutiny of glaring energy and resource security gaps in the post-Cold War era. War, of course, is not new, nor is Russia’s aggression a unique threat to global energy security or decarbonization. However, as a nuclear-armed and energy export-intensive state engaged in an unprovoked attack on a neighboring country, Russia’s actions do pose novel challenges to national energy, security, and climate priorities.