by Sarah Firisen

Over the last few weeks, I’ve been spending more time in the office than I have since the start of COVID. I work for a technology start-up, and our New York office used to look and feel just as shows like Silicon Valley portrayed such offices: cool furniture, fancy coffee machines, lots of free snacks, gaming systems and board games piled up in a dedicated room, and lots of young people who gave the office a fun, high energy, even if noisy, vibe. But this visit, while the snacks and coffee machines are still there, the office has a rather ghost town-like feel. There’s been no mandate to return to the office, so for the most part, people haven’t. Every day I saw my colleague Andy who lives in a Manhattan apartment that’s too crowded with family and a dog. He escapes to the office for some peace of quiet. Then there was the receptionist and the facilities manager, who had no choice but to be there. But that was it for regulars. The odd person would float in for a bit, have a meeting, then leave. Is this the future of office life?

Over the last few weeks, I’ve been spending more time in the office than I have since the start of COVID. I work for a technology start-up, and our New York office used to look and feel just as shows like Silicon Valley portrayed such offices: cool furniture, fancy coffee machines, lots of free snacks, gaming systems and board games piled up in a dedicated room, and lots of young people who gave the office a fun, high energy, even if noisy, vibe. But this visit, while the snacks and coffee machines are still there, the office has a rather ghost town-like feel. There’s been no mandate to return to the office, so for the most part, people haven’t. Every day I saw my colleague Andy who lives in a Manhattan apartment that’s too crowded with family and a dog. He escapes to the office for some peace of quiet. Then there was the receptionist and the facilities manager, who had no choice but to be there. But that was it for regulars. The odd person would float in for a bit, have a meeting, then leave. Is this the future of office life?

Some companies have recalled workers to the office, at the least for a few days every week. But many haven’t, and perhaps never will. About seven months into the COVID pandemic, I questioned what the future of work would look like, “employee productivity is up. There have been enormous savings from lack of business travel and reduced real estate costs for many companies. We now know that, for the most part, we do have the technology infrastructure to support remote working at scale. This convergence of technology, employee productivity, and increased profitability for companies means that, for many people, some version of our current home office life will continue indefinitely.” A year and a half later, there’s no doubt that, while people miss some of the social aspects of on-site working, there are lots of things they don’t miss. Read more »

We arrived in Berkeley and found it to be a pleasant place to live. I always have a partiality for small university towns that are culturally and politically alive. And yet Berkeley is not far from a thriving major city (San Francisco—“the unfettered city/resounds with hedonistic glee”, as Vikram Seth describes it in his verse-novel The Golden Gate) on the one hand, and from wide-open spaces on the other. Nature in Berkeley itself is quite beautiful, nestled as it is on a leafy hillside and facing an ocean and its bay, with gorgeous sunsets over the Golden Gate Bridge (on days when it is not shrouded by the mysterious fog—which appears almost as a character in San Francisco noir, like in the crime novels of Dashiell Hammett). Once driving in the dense fog in a winding street in the Berkeley hills I missed a turn and lost my way; I fondly remembered that famous scene in Fellini’s semi-autobiographical film Amarcord, where one winter-day in Rimini, his childhood town, the fog shrouds everything, the piazza disappears, and the grandpa loses his way home.

We arrived in Berkeley and found it to be a pleasant place to live. I always have a partiality for small university towns that are culturally and politically alive. And yet Berkeley is not far from a thriving major city (San Francisco—“the unfettered city/resounds with hedonistic glee”, as Vikram Seth describes it in his verse-novel The Golden Gate) on the one hand, and from wide-open spaces on the other. Nature in Berkeley itself is quite beautiful, nestled as it is on a leafy hillside and facing an ocean and its bay, with gorgeous sunsets over the Golden Gate Bridge (on days when it is not shrouded by the mysterious fog—which appears almost as a character in San Francisco noir, like in the crime novels of Dashiell Hammett). Once driving in the dense fog in a winding street in the Berkeley hills I missed a turn and lost my way; I fondly remembered that famous scene in Fellini’s semi-autobiographical film Amarcord, where one winter-day in Rimini, his childhood town, the fog shrouds everything, the piazza disappears, and the grandpa loses his way home. I said last week that Putin has “taken the world hostage” by threatening to use nuclear weapons in order to defend the territorial sovereignty of Russia, and I certainly count my own mind and faculty of attention among the captives. Some of you might be tired of this subject by now, which now enters its fourth week as my exclusive focus in this space. I expect I’ll get back to regular programming soon, as, God willing, the font size of the New York Times’ front-page headlines begins at long last to shrink back to something closer to normal. You might be particularly tired of hearing from me on the subject, as plainly what you are seeing here is not expert analysis, such as you might expect from, say, Timothy Snyder or Anne Applebaum, but rather the essayistic laying bare of unstable convictions, fleeting worries, and divinations from long-ago memories of formative experiences in Russia.

I said last week that Putin has “taken the world hostage” by threatening to use nuclear weapons in order to defend the territorial sovereignty of Russia, and I certainly count my own mind and faculty of attention among the captives. Some of you might be tired of this subject by now, which now enters its fourth week as my exclusive focus in this space. I expect I’ll get back to regular programming soon, as, God willing, the font size of the New York Times’ front-page headlines begins at long last to shrink back to something closer to normal. You might be particularly tired of hearing from me on the subject, as plainly what you are seeing here is not expert analysis, such as you might expect from, say, Timothy Snyder or Anne Applebaum, but rather the essayistic laying bare of unstable convictions, fleeting worries, and divinations from long-ago memories of formative experiences in Russia. Herd immunity was always our greatest asset for protecting vulnerable people, but public health failed to use it wisely.

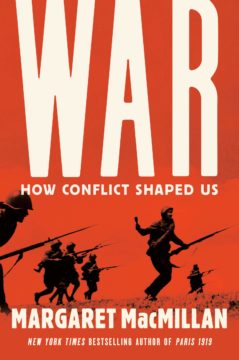

Herd immunity was always our greatest asset for protecting vulnerable people, but public health failed to use it wisely. War is a not a word that communicates much. It wants to, but quickly the gruff sound deteriorates into an abstraction and nothing more. War. War. Like love, truth, or beauty, we say the word but cannot see it. The gut does not believe. To title a book War as Margaret MacMillan, the distinguished historian, has done, is to attempt to assert control over the very term itself. As a result, even before the prose begins, War: How Conflict Shaped Us promises to be a revelation: here, war will be understood at last. Such authoritativeness is a noble pursuit, and MacMillan joins others in recent years such as Sebastian Junger and Jeremy Black in a frantic effort to articulate a unified field theory of war before it is too late.¹ “We face the prospect of the end of humanity itself,” MacMillan concludes, if we fail to demystify war in our current moment. (289) That is the project, and given the book’s critical and popular praise from notable figures such as war journalist Dexter Filkins, former National Security Director H.R. McMaster, and former Secretary of State George Schultz, readers might feel it has done its work. I am not so sure, which is not a criticism of MacMillan’s book so much as it is a lament about the relentless inscrutability of war both as an object of academic study and as a lived experience that resists expression.

War is a not a word that communicates much. It wants to, but quickly the gruff sound deteriorates into an abstraction and nothing more. War. War. Like love, truth, or beauty, we say the word but cannot see it. The gut does not believe. To title a book War as Margaret MacMillan, the distinguished historian, has done, is to attempt to assert control over the very term itself. As a result, even before the prose begins, War: How Conflict Shaped Us promises to be a revelation: here, war will be understood at last. Such authoritativeness is a noble pursuit, and MacMillan joins others in recent years such as Sebastian Junger and Jeremy Black in a frantic effort to articulate a unified field theory of war before it is too late.¹ “We face the prospect of the end of humanity itself,” MacMillan concludes, if we fail to demystify war in our current moment. (289) That is the project, and given the book’s critical and popular praise from notable figures such as war journalist Dexter Filkins, former National Security Director H.R. McMaster, and former Secretary of State George Schultz, readers might feel it has done its work. I am not so sure, which is not a criticism of MacMillan’s book so much as it is a lament about the relentless inscrutability of war both as an object of academic study and as a lived experience that resists expression. They were in lines extending as far as the eye could see, stretching across the horizon and toward the Promised Land. Dutifully, though with growing impatience and anxiety, they were waiting their turn to enter the fabled American Dreamland, where all who worked hard would be assured well-paid jobs and comfortable homes where well-adjusted children would flourish, and smile their winning smiles.

They were in lines extending as far as the eye could see, stretching across the horizon and toward the Promised Land. Dutifully, though with growing impatience and anxiety, they were waiting their turn to enter the fabled American Dreamland, where all who worked hard would be assured well-paid jobs and comfortable homes where well-adjusted children would flourish, and smile their winning smiles. A fully paralyzed man with ALS, or

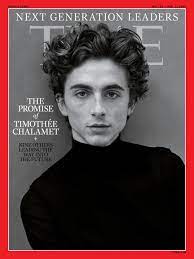

A fully paralyzed man with ALS, or  If Chalamet—whom most people call, affectionately, Timmy—sees himself as off-center, so far it’s working. He’s back in New York for the Met Gala, which he’s co-chairing alongside

If Chalamet—whom most people call, affectionately, Timmy—sees himself as off-center, so far it’s working. He’s back in New York for the Met Gala, which he’s co-chairing alongside  Konstantin Olmezov in n+1:

Konstantin Olmezov in n+1: Rajan Menon in Boston Review:

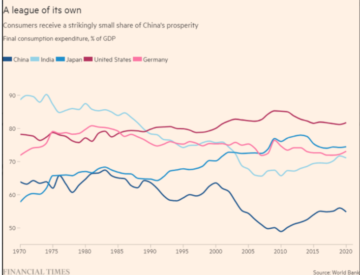

Rajan Menon in Boston Review: Adam Tooze debates Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu on whether China can make the adjustments necessary to sustain growth.

Adam Tooze debates Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu on whether China can make the adjustments necessary to sustain growth.  James Meadway in Sidecar:

James Meadway in Sidecar: But as Green says, and his book splendidly demonstrates, “what has disappeared beneath sea can rebuild itself in the mind”. Since the 13th century, when the Suffolk coastline by Dunwich began to be seriously gnawed by the waves, thousands of settlements have disappeared from our maps. It is the untold story of these lost communities – “Britain’s shadow topography” – that has become Green’s obsession. He disinters their rich history and reimagines the lives of those who walked their streets, revealing “tales of human perseverance, obsession, resistance and reconciliation”. By doing so, he makes tangible the tragedy of their loss and the threat we all face from the climate crisis on these storm-tossed islands.

But as Green says, and his book splendidly demonstrates, “what has disappeared beneath sea can rebuild itself in the mind”. Since the 13th century, when the Suffolk coastline by Dunwich began to be seriously gnawed by the waves, thousands of settlements have disappeared from our maps. It is the untold story of these lost communities – “Britain’s shadow topography” – that has become Green’s obsession. He disinters their rich history and reimagines the lives of those who walked their streets, revealing “tales of human perseverance, obsession, resistance and reconciliation”. By doing so, he makes tangible the tragedy of their loss and the threat we all face from the climate crisis on these storm-tossed islands.