From NPR:

The dream of animal-to-human transplants — or xenotransplantation — goes back to the 17th century with stumbling attempts to use animal blood for transfusions. By the 20th century, surgeons were attempting transplants of organs from baboons into humans, notably Baby Fae, a dying infant, who lived 21 days with a baboon heart.

With no lasting success and much public uproar, scientists turned from primates to pigs, tinkering with their genes to bridge the species gap. Pigs have advantages over monkeys and apes. They are produced for food, so using them for organs raises fewer ethical concerns. Pigs have large litters, short gestation periods and organs comparable to humans. Pig heart valves also have been used successfully for decades in humans. The blood thinner heparin is derived from pig intestines. Pig skin grafts are used on burns and Chinese surgeons have used pig corneas to restore sight.

In the NYU case, researchers kept a deceased woman’s body going on a ventilator after her family agreed to the experiment. The woman had wished to donate her organs, but they weren’t suitable for traditional donation. The family felt “there was a possibility that some good could come from this gift,” Montgomery said. Montgomery himself received a transplant three years ago, a human heart from a donor with hepatitis C because he was willing to take any organ. “I was one of those people lying in an ICU waiting and not knowing whether an organ was going to come in time,” he said.

Several biotech companies are in the running to develop suitable pig organs for transplant to help ease the human organ shortage. More than 90,000 people in the U.S. are in line for a kidney transplant. Every day, 12 die while waiting.

More here.

Immunotherapy is a promising strategy to treat cancer by stimulating the body’s own immune system to destroy tumor cells, but it only works for a handful of cancers. MIT researchers have now discovered a new way to jump-start the immune system to attack tumors, which they hope could allow immunotherapy to be used against more types of cancer.

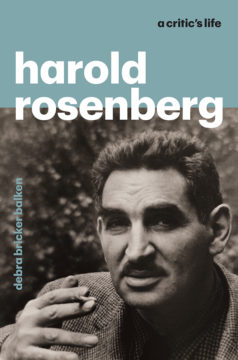

Immunotherapy is a promising strategy to treat cancer by stimulating the body’s own immune system to destroy tumor cells, but it only works for a handful of cancers. MIT researchers have now discovered a new way to jump-start the immune system to attack tumors, which they hope could allow immunotherapy to be used against more types of cancer. Teaching writing, unlike most other kinds of teaching, is an intervention, closer to therapy than to any transmissible instruction. But with all the fussing about craft — anyone who teaches has a personal punch-list — we almost never hear about or get close to the real business, the meld. Maybe because each teacher is different and each interaction draws on a unique set of human variables.

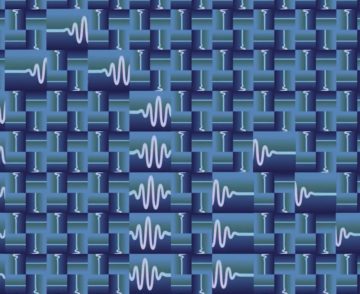

Teaching writing, unlike most other kinds of teaching, is an intervention, closer to therapy than to any transmissible instruction. But with all the fussing about craft — anyone who teaches has a personal punch-list — we almost never hear about or get close to the real business, the meld. Maybe because each teacher is different and each interaction draws on a unique set of human variables. In an increasingly data-driven world, mathematical tools known as wavelets have become an indispensable way to analyze and understand information. Many researchers receive their data in the form of continuous signals, meaning an unbroken stream of information evolving over time, such as a geophysicist listening to sound waves bouncing off of rock layers underground, or a data scientist studying the electrical data streams obtained by scanning images. These data can take on many different shapes and patterns, making it hard to analyze them as a whole or to take them apart and study their pieces — but wavelets can help.

In an increasingly data-driven world, mathematical tools known as wavelets have become an indispensable way to analyze and understand information. Many researchers receive their data in the form of continuous signals, meaning an unbroken stream of information evolving over time, such as a geophysicist listening to sound waves bouncing off of rock layers underground, or a data scientist studying the electrical data streams obtained by scanning images. These data can take on many different shapes and patterns, making it hard to analyze them as a whole or to take them apart and study their pieces — but wavelets can help. Sheng, a professor of composition at the University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theater, and Dance, said he was sorry for showing a 1965 film version of Othello, starring Laurence Olivier in blackface, during an undergraduate class last month. In the first apology, sent to students shortly after the class ended, he called the film’s use of blackface “racially insensitive and outdated” and wrote that it was “wrong for me” to show it. He promised they would discuss the issue in the next class. As it turns out, he wouldn’t get that chance.

Sheng, a professor of composition at the University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theater, and Dance, said he was sorry for showing a 1965 film version of Othello, starring Laurence Olivier in blackface, during an undergraduate class last month. In the first apology, sent to students shortly after the class ended, he called the film’s use of blackface “racially insensitive and outdated” and wrote that it was “wrong for me” to show it. He promised they would discuss the issue in the next class. As it turns out, he wouldn’t get that chance. Yet the fact remains that

Yet the fact remains that  The wager made by Atkins is that if reality can be derealized by such technologies, it might also be rediscovered there, and this might occur in a few ways. First, he believes that, once outmoded, technology passes over to the side of “base materiality”; its very clunkiness becomes a reality effect. Atkins adapts the term corpsing—the moment when an actor breaks character and so dispels the illusion of the performance—“to describe a kind of structural revelation more generally”; his examples are when a vinyl record jumps or a streaming movie buffers. To corpse a medium is to expose its materiality, even to underscore its mortality, and in this moment the real might poke through. Second, punctuated by the gestural tics of the Atkins avatar, The Worm is also rife with manufactured glitches—sudden blurs, flares, beeps, and crackles—and these apparent cracks in the artifice might provide another opening to the real. Although these reality effects are artificial, “they baffle the signs of reality by parodying them, engendering a new kind of realism.”7 Third, if the real might be felt when an illusion fails, so too might it be sensed when that illusion is “glazed with effects to italicize the artifice,” that is, when illusionism is pushed to a hyperreal point.

The wager made by Atkins is that if reality can be derealized by such technologies, it might also be rediscovered there, and this might occur in a few ways. First, he believes that, once outmoded, technology passes over to the side of “base materiality”; its very clunkiness becomes a reality effect. Atkins adapts the term corpsing—the moment when an actor breaks character and so dispels the illusion of the performance—“to describe a kind of structural revelation more generally”; his examples are when a vinyl record jumps or a streaming movie buffers. To corpse a medium is to expose its materiality, even to underscore its mortality, and in this moment the real might poke through. Second, punctuated by the gestural tics of the Atkins avatar, The Worm is also rife with manufactured glitches—sudden blurs, flares, beeps, and crackles—and these apparent cracks in the artifice might provide another opening to the real. Although these reality effects are artificial, “they baffle the signs of reality by parodying them, engendering a new kind of realism.”7 Third, if the real might be felt when an illusion fails, so too might it be sensed when that illusion is “glazed with effects to italicize the artifice,” that is, when illusionism is pushed to a hyperreal point. In a laboratory in Israel, an incubator drum spins on a bench. The two glass bottles attached to the drum contain mouse embryos, each the size of a grain of rice, with translucent, pulsing hearts.

In a laboratory in Israel, an incubator drum spins on a bench. The two glass bottles attached to the drum contain mouse embryos, each the size of a grain of rice, with translucent, pulsing hearts. It can happen here. The “it” ought to be obvious by now: an authoritarian or even fascist regime in the United States. That was a big reason why Harvard professor Steven Levitsky, along with his colleague Daniel Ziblatt, published the 2018 book “

It can happen here. The “it” ought to be obvious by now: an authoritarian or even fascist regime in the United States. That was a big reason why Harvard professor Steven Levitsky, along with his colleague Daniel Ziblatt, published the 2018 book “ Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible.

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible. Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.