by Deanna K. Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

A few years ago a brief blog post made the rounds on social media: the blogger had uploaded a photo of a single page of an academic book with the lead-in “This May Be the Best ‘Acknowledgments’ Section of All Time.” The page itself read:

I blame all of you. Writing this book has been an exercise in sustained suffering. The casual reader may, perhaps, exempt herself from excessive guilt, but for those of you who have played the larger role in prolonging my agonies with your encouragement and support, well … you know who you are, and you owe me.

Ha ha ha ha ha ha! Ha.

At first I found the performance mildly amusing, as presumably did all the people who retweeted it and posted it on Facebook. But after the quick flash of cynical recognition faded, it just depressed me. Yes it’s a good joke—of that particular genre of academic humor that pretends to be wryly self-deprecating but is really wryly self-congratulatory. (See, for example, the wonderful moment in 30 Rock when Jack Donaghy and Liz Lemon comfort themselves after doing something particularly dastardly: “[Jack] We might not be the best people…. [Liz] But we’re not the worst! [In unison] Graduate students are the worst.”) Of course there’s nothing wrong with being self-congratulatory in an Acknowledgments section; that’s one of its core functions—the business of actually thanking people aside. What really depressed me about this one was the thought that its author, in the service of a joke, had thrown away his one opportunity to publicly express gratitude to the people who had supported and encouraged him throughout the arduous process of writing an academic monograph. Why would anyone do that? Read more »

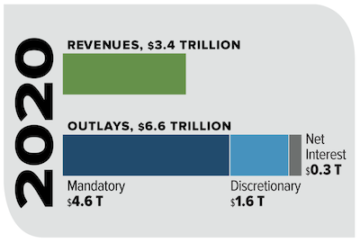

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide.

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide. Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”

Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”  Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.

Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.

Clairvoyant of the Small, Susan Bernofsky’s long-awaited biography of the Swiss modernist writer Robert Walser, is erudite, painstakingly thorough, and sensitively written. Readers of Walser finally have a volume that connects the development of the writer’s work and its publishing history to the various episodes of his peripatetic adult life in the cities of Biel, Bern, Zurich, Berlin, and finally the sanatoriums in Waldau and later Herisau, where Walser—revered by Franz Kafka and Max Brod, Walter Benjamin, W. G. Sebald, and many others—presumably ceased writing altogether.

Clairvoyant of the Small, Susan Bernofsky’s long-awaited biography of the Swiss modernist writer Robert Walser, is erudite, painstakingly thorough, and sensitively written. Readers of Walser finally have a volume that connects the development of the writer’s work and its publishing history to the various episodes of his peripatetic adult life in the cities of Biel, Bern, Zurich, Berlin, and finally the sanatoriums in Waldau and later Herisau, where Walser—revered by Franz Kafka and Max Brod, Walter Benjamin, W. G. Sebald, and many others—presumably ceased writing altogether.

Men have always wanted to fly to the moon and stars. We wanted to find out what was up there on the moon and planets? Was it heaven? Were there angels? Or were these worlds inhabited by strange creatures who built canals? We looked up, we used telescopes. We watched the stars and charted their movements. But we wanted to do more than look and imagine; we wanted to go up there and see for ourselves? The birds could fly, why couldn’t we?

Men have always wanted to fly to the moon and stars. We wanted to find out what was up there on the moon and planets? Was it heaven? Were there angels? Or were these worlds inhabited by strange creatures who built canals? We looked up, we used telescopes. We watched the stars and charted their movements. But we wanted to do more than look and imagine; we wanted to go up there and see for ourselves? The birds could fly, why couldn’t we?

My Presidency College friend Premen was always a voracious reader, particularly of political, social and military history. He often told me of new books in those areas and sometimes persuaded me to read them. But by the time I saw him again in Cambridge, I could see his slow turn from his fascination with Trotsky to Mao. This was in line with a general movement among the young in the European left around that time. Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise captured the restless energy of politically-activist students in contemporary France, foreshadowing the student rebellions in a year or so.

My Presidency College friend Premen was always a voracious reader, particularly of political, social and military history. He often told me of new books in those areas and sometimes persuaded me to read them. But by the time I saw him again in Cambridge, I could see his slow turn from his fascination with Trotsky to Mao. This was in line with a general movement among the young in the European left around that time. Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise captured the restless energy of politically-activist students in contemporary France, foreshadowing the student rebellions in a year or so. Fatalism creeps across our movements like rust. In conversations with scientists and activists, I hear the same words, over and again: “We’re screwed.” Government plans are too little, too late. They are unlikely to prevent the Earth’s systems from flipping into new states hostile to

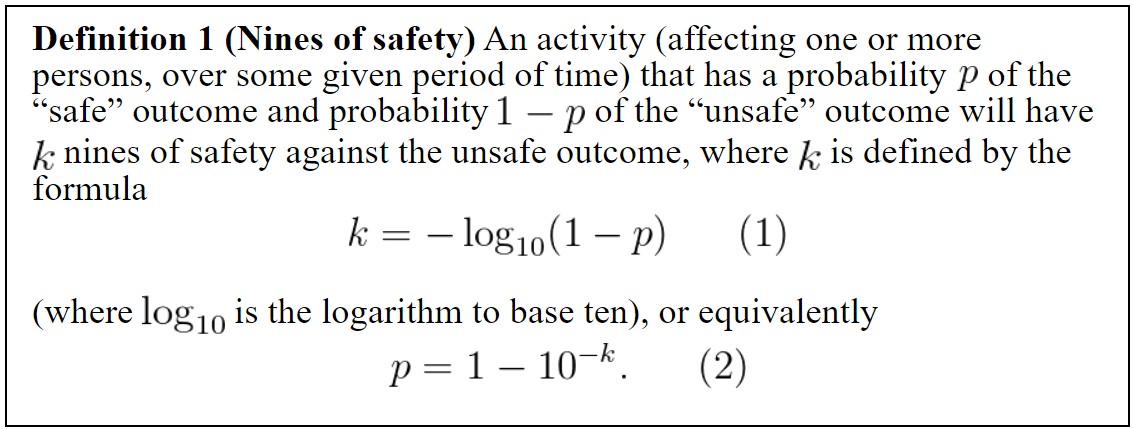

Fatalism creeps across our movements like rust. In conversations with scientists and activists, I hear the same words, over and again: “We’re screwed.” Government plans are too little, too late. They are unlikely to prevent the Earth’s systems from flipping into new states hostile to  Because of all the very different ways in which percentages could be used, I think it may make sense to propose an alternate system of units to measure one class of probabilities, namely the probabilities of avoiding some highly undesirable outcome, such as death, accident or illness. The units I propose are that of “

Because of all the very different ways in which percentages could be used, I think it may make sense to propose an alternate system of units to measure one class of probabilities, namely the probabilities of avoiding some highly undesirable outcome, such as death, accident or illness. The units I propose are that of “ Psychology, as a scientific discipline in its own right, appears towards the end of the nineteenth century at roughly the moment when it is no longer possible in respectable institutions to speak of the soul. To put this another way, the science of the soul, which is all the word “psychology” means, begins only when those concerned with it declare the soul off-limits within the scope of their science. This might seem paradoxical, but in fact it is a common pattern: “biology” comes into its own, too, only when it ceases for the most part to look for that special je-ne-sais-quoi we call “life” that would somehow place living beings at a different ontological rank on some imagined “scale of being” from helium or silica, and just gets down to the business of accounting for how a certain class of carbon-based compounds do their thing. Philosophy for its part would still be able to talk about the soul in some limited contexts, but typically only as an occasion for investigating other conceptual problems or as shorthand for the gedankenexperimental fiction of a fully disembodied conscious being. Still, “Does the soul exist?” remains even today a legitimate topic of inquiry in a typical Intro to Philosophy course, though I suspect many instructors rush at the beginning of this segment to reassure their students that they personally know full well that it does not.

Psychology, as a scientific discipline in its own right, appears towards the end of the nineteenth century at roughly the moment when it is no longer possible in respectable institutions to speak of the soul. To put this another way, the science of the soul, which is all the word “psychology” means, begins only when those concerned with it declare the soul off-limits within the scope of their science. This might seem paradoxical, but in fact it is a common pattern: “biology” comes into its own, too, only when it ceases for the most part to look for that special je-ne-sais-quoi we call “life” that would somehow place living beings at a different ontological rank on some imagined “scale of being” from helium or silica, and just gets down to the business of accounting for how a certain class of carbon-based compounds do their thing. Philosophy for its part would still be able to talk about the soul in some limited contexts, but typically only as an occasion for investigating other conceptual problems or as shorthand for the gedankenexperimental fiction of a fully disembodied conscious being. Still, “Does the soul exist?” remains even today a legitimate topic of inquiry in a typical Intro to Philosophy course, though I suspect many instructors rush at the beginning of this segment to reassure their students that they personally know full well that it does not. Springsteen From when I was a young man, I lived with a man who suffered a loss of status and I saw it every single day. It was all tied to lack of work, and I just watched the low self-esteem. That was a part of my daily life living with my father. It taught me one thing: work is essential. That’s why if we can’t get people working in this country, we’re going to have an awful hard time.

Springsteen From when I was a young man, I lived with a man who suffered a loss of status and I saw it every single day. It was all tied to lack of work, and I just watched the low self-esteem. That was a part of my daily life living with my father. It taught me one thing: work is essential. That’s why if we can’t get people working in this country, we’re going to have an awful hard time. In 2019, over the course of a chilly February weekend, the Catholic Church seemed as though it was on the verge of a reckoning. For four days, Pope Francis convened a gathering of bishops in Vatican City for the Church’s first ever sexual abuse summit. Since becoming Pope in 2013, Francis has developed a reputation as a moderniser whose dedication to social justice could overcome the Church’s unwillingness to deal with a scandal that has lost it many followers in recent decades. The Pope said he wanted to address the generations-long delay in dealing with the sexual abuse of children by priests and other clergymen over decades across the world. In front of an audience of 180 bishops and cardinals, Pope Francis spoke of monstrous acts of evil and, ultimately, of justice. It was hailed as a defining moment in his leadership. At last, it seemed, the Catholic Church was ready to reform itself.

In 2019, over the course of a chilly February weekend, the Catholic Church seemed as though it was on the verge of a reckoning. For four days, Pope Francis convened a gathering of bishops in Vatican City for the Church’s first ever sexual abuse summit. Since becoming Pope in 2013, Francis has developed a reputation as a moderniser whose dedication to social justice could overcome the Church’s unwillingness to deal with a scandal that has lost it many followers in recent decades. The Pope said he wanted to address the generations-long delay in dealing with the sexual abuse of children by priests and other clergymen over decades across the world. In front of an audience of 180 bishops and cardinals, Pope Francis spoke of monstrous acts of evil and, ultimately, of justice. It was hailed as a defining moment in his leadership. At last, it seemed, the Catholic Church was ready to reform itself.